Note: This bilingual article appears first in Spanish and then in English.

Silvia Arrom, profesora emérita de Estudios Latinoamericanos de la Universidad de Brandeis, es presidenta de la XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México (Austin, 30 de octubre al 2 de noviembre). Arrom ha tenido una larga y distinguida carrera académica, publicando ampliamente sobre la historia social de México, con libros que incluyen su más reciente publicación, La Güera Rodríguez: Mito y mujer (México: Turner Noema, 2020), así como numerosos libros y artículos sobre la mujer, el género, el bienestar social, y los pobres.[1] Conversó con Madeleine Olson, estudiante de posgrado de la UT-Austin.

Madeleine Olson: La Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México lleva más de setenta años celebrándose en Norteamérica—su primera reunión tuvo lugar en Monterrey en 1949. Cuénteme más sobre su experiencia e historia con la conferencia.

Silvia Arrom: La Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México fue una de las primeras conferencias profesionales a las que asistí como doctora de nuevo cuño, cuando se celebró en Chicago en 1981. A lo largo de los años, he visto como la organización ha crecido, se ha vuelto más acogedora para las mujeres, y ha incluido cada vez más historia social, lo cual refleja unos cambios saludables en el campo. Siempre me ha impresionado la variedad y la calidad de los trabajos sobre la historia de México.

Olson: El tema de este año para el congreso, “Los federalismos en la historia de México y del Texas mexicano,” se centra en la manera en que México y sus vecinos han intentado poner en práctica las promesas de un federalismo unido. ¿Cuáles son algunas de las lecciones que nosotros, como historiadores, y principalmente como historiadores sociales, podemos tomar al centrarnos en este tema, y cómo podemos aplicarlas en la actualidad?

Arrom: Un tema preeminente para el periodo republicano de México (1824-1857) es el conflicto entre el federalismo y el centralismo. La narrativa de los historiadores enfatiza la debilidad del Estado mexicano, que trataba de unir el país pero sin mucho éxito – un paso adelante, pero dos para atrás. Los historiadores suelen afirmar que la Constitución de 1857 y la Reforma permitieron la fusión del regionalismo en México, por lo que a partir de ahí, la narrativa dominante gira en torno a la consolidación y el fortalecimiento del Estado central. Sin embargo, me parece que nosotros los historiadores no le hemos hecho bastante caso al regionalismo. Lo que yo he aprendido, especialmente al investigar la asistencia social, es que el Estado fue mucho más débil y fragmentario de lo que solemos suponer durante el porfiriato (1876-1910) y luego durante el periodo posrevolucionario (1917 en adelante). De hecho, había muchas regiones donde tenía muy poca presencia.

Al observar cómo funcionaba el sistema de asistencia social en la práctica, se hace evidente que las instituciones públicas de bienestar eran muy escasas, dispersas y lamentablemente inadecuadas. Las organizaciones privadas, muchas veces religiosas, llenaban el vacío, sobre todo fuera de las grandes ciudades. Pero los historiadores han creído la narrativa del Estado como Padre de los Pobres, en que la beneficencia pública reemplaza la caridad, y han ignorado las contribuciones de las organizaciones privadas y religiosas.

Hoy, cuando observamos el resquebrajamiento del estado de derecho en muchas regiones de México, deberíamos cuestionar la narrativa de la consolidación continua del Estado. Parte de esa narrativa es cierta, pero se enfoca demasiado en la mitad del vaso medio lleno, y yo creo que debemos concentrarnos en la parte medio vacía, o sea, que debemos reconocer las debilidades del Estado, su presencia desigual en el territorio mexicano, sus ausencias, y cómo ha funcionado a través de actores locales. Estos actores son fundamentales ya que, con frecuencia, el Estado les ha delegado la autoridad, lo que da la apariencia de que hay una presencia estatal en esa zona. Me refiero, por ejemplo, al funcionamiento de las fuerzas policiacas de voluntarios (las defensas rurales) en muchos pueblos durante todo el último siglo.

En vez de fijarnos tanto en la legislación y las altas esferas del gobierno, los historiadores deberíamos estudiar cómo se ve el Estado desde la base, a nivel local, para entender cómo ha impactado la vida de individuos. Esto nos obligará a resucitar parte de esa antigua narrativa de un Estado débil e incompleto que lucha, pero no siempre logra unir a las regiones diversas, y que tampoco reemplaza progresivamente a la Iglesia o las organizaciones privadas. En resumen, los estudiosos debemos cuestionar más la propaganda del Estado liberal y luego del revolucionario.

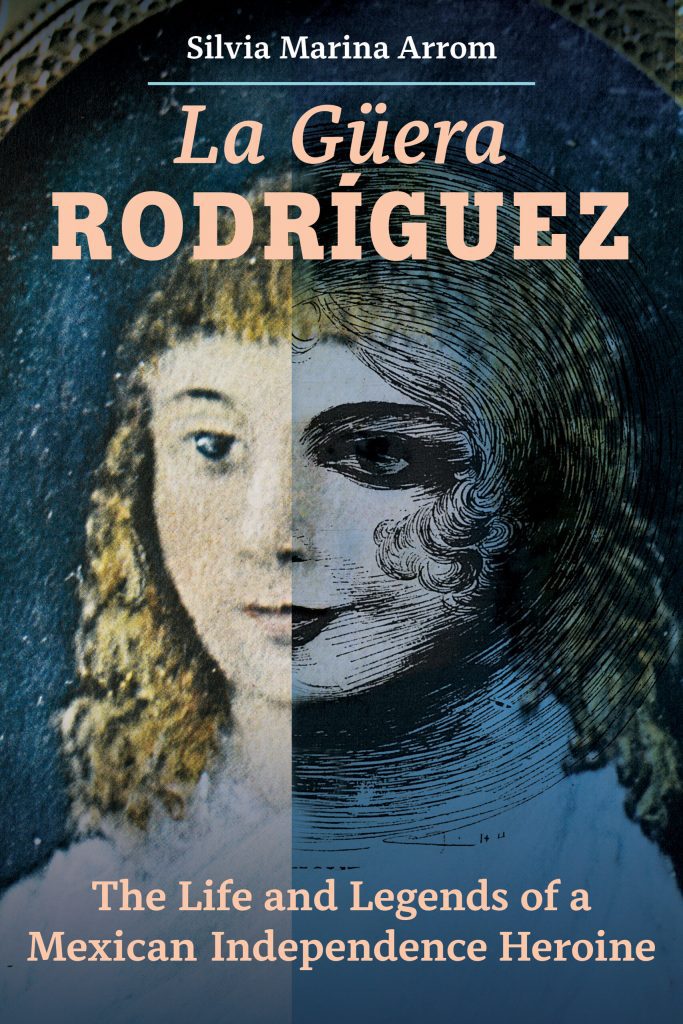

Olson: Su libro más reciente, La Güera Rodríguez: Mito y mujer, abarca el periodo federalista en México y sigue no solamente la vida de la legendaria heroína María Ignacia Rodríguez de Velasco, sino también el uso de su historia en la cultura popular después de su muerte. ¿Cuál fue su experiencia durante la Independencia y su esperanza para el futuro de México?

Arrom: Mi libro sobre La Güera (como siempre se le conocía porque era muy rubia) examina tanto su vida como su trayectoria póstuma en las artes y letras mexicanas. Durante su vida fue conocida como una bella y encantadora dama. No fue hasta el siglo XX que se convirtió en una heroína de la independencia, que es uno de muchos mitos que circulan sobre ella.

En realidad, ella no parece haber sido una gran heroína. Nunca se manifestó abiertamente a favor de la independencia y nunca fue juzgada o castigada por insurgente, como fueron muchas otras mujeres. Además, nos quedan muy pocas cartas de su puño y letra. Así que casi no tenemos documentos que aclaren sus posiciones políticas o sus deseos para el futuro de México.

Sin embargo, sabemos que en 1808 formaba parte de un grupo de criollos centrado en el ayuntamiento de la ciudad de México que favorecía un autogobierno provisional hasta que los invasores franceses abandonaran España y Fernando VII pudiera volver al trono. Este grupo quería la autonomía, pero todavía no la ruptura con la madre patria. En 1809, la Güera estuvo involucrada en una conspiración contra el líder del Golpe de Yermo que había socavado ese proyecto, lo que la llevó a ser desterrada de la ciudad de México durante unos meses y a exiliarse en Querétaro. Los archivos muy detallados sobre este incidente no mencionan que ella quisiera la independencia. Solamente dicen que la intriga se basó en resentimientos personales y que, al difundir demasiados rumores, La Güera exacerbaba las tensiones en la capital. Por lo tanto, parece que ella era un nexo crítico en la red de información de la época que iba de boca en boca, porque era muy sociable y chismosa.

Después de regresar a la Ciudad de México, vivió discretamente y se cuidó de meterse en problemas. Después de todo, en 1810 La Güera era una viuda con cinco hijos y no podía arriesgarse a un nuevo castigo. No obstante, sabemos que por lo menos en una ocasión dio dinero a los rebeldes que ocupaban sus valiosas haciendas, probablemente para protegerlas más que por simpatía a la causa. Fue en vano, porque los rebeldes las dejaron en la ruina y ella perdió su principal fuente de ingresos.

Su historia representa, creo, la de muchas personas que vivieron los años de guerra como una época de crisis e inseguridad económica, que no sabían qué posición tomar, y que trataron de quedar bien con todos los bandos para proteger a su familia y patrimonio ante todo. Esta narrativa contrasta con la historia que a los historiadores les gusta contar sobre el periodo de la independencia porque no todo es tan claro, más bien se trata de una historia de ambivalencias, de vacilación y sufrimiento. No es la típica historia triunfalista, sino algo mucho más complicado.

Solamente fue en 1949, cuando Artemio del Valle-Arizpe escribió una novela histórica sobre La Güera, que ella captó de nuevo la atención pública. Al inventar muchos datos y manipular otros, el autor creó el mito de que ella fue heroína desafiante y liviana seductora quien tuvo amoríos ilícitos con los hombres principales de la época de la independencia. Sus cuentos eran tan atractivos que han sido repetidos—y engalanados—para crear la figura legendaria de una mujer fuerte y liberada que también era una patriota intrépida.

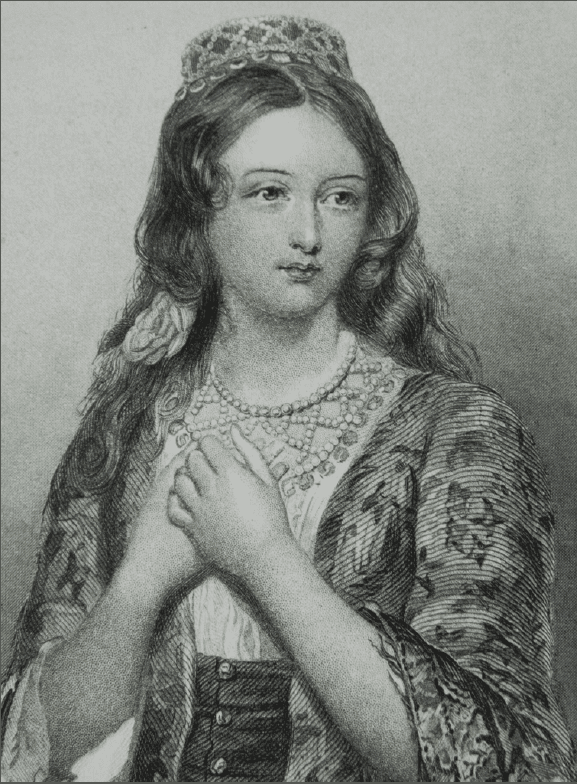

“Portrait” of the mythical Güera Rodríguez

“Retrato” de la Güera Rodríguez del mito

Fuente / Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Only known genuine portrait of la Güera Rodríguez

Único retrato genuino que se conoce de la Güera Rodríguez

Unknown artist, c. 1794. Reproduced in the catalog, Veinte mujeres notables en la vida de México. Mexico City, Instituto Mexicano Norteamericano de Relaciones Culturales, 1974.

Artista desconocido, c. 1794. Reproducido en el catálogo, Veinte mujeres notables en la vida de México. México: Instituto Mexicano Norteamericano de Relaciones Culturales, 1974.

Olson: Dice que empezó a pensar este libro siendo estudiante. ¿Cómo ha cambiado la investigación como proceso a lo largo de su carrera y en relación con su idea de lo que debe ser el papel de la historia social en la academia?

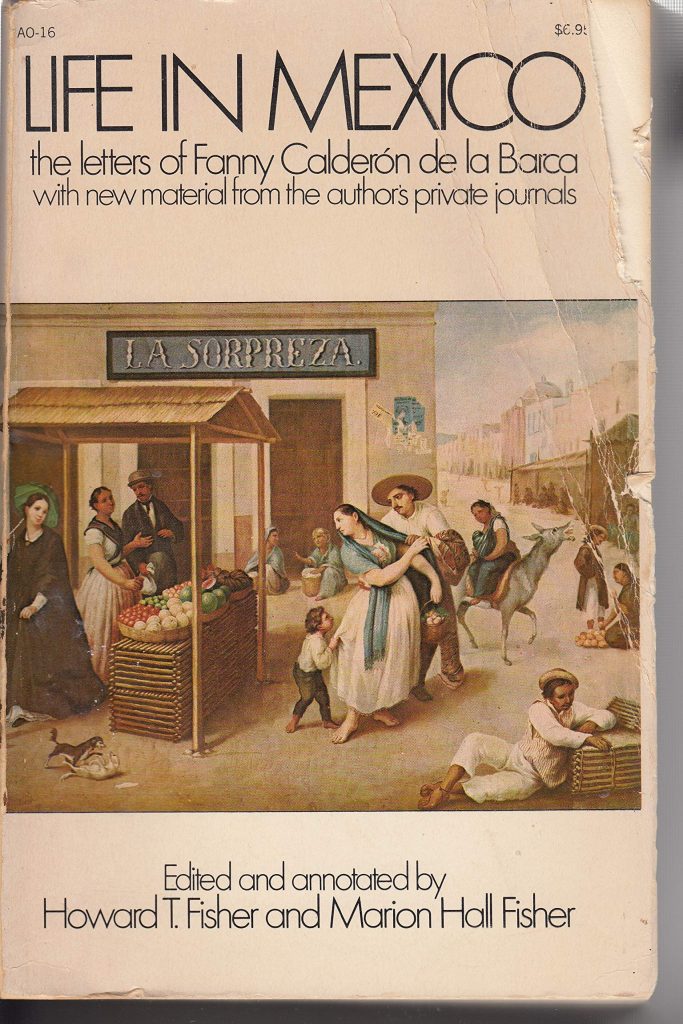

Arrom: La Güera me ha fascinado desde que, en un seminario universitario, leí La vida en México, de Fanny Calderón de la Barca. Este libro cambió el rumbo de mi vida. Siempre estuve interesada en Latinoamérica porque mis padres eran cubanos, pero este libro me convirtió en mexicanista y me abrió los ojos a la historia social. En una época en que los textos de historia se enfocaban en los eventos políticos y militares, aunados a un poco de historia económica e intelectual, este libro hablaba de las mujeres y la familia, los pobres, y las relaciones sociales. Ahora me doy cuenta de que he dedicado toda mi carrera a estudiar esos temas, en el mismo lugar y periodo al que me introdujo Fanny.

Entonces, de estudiante de doctorado, recorría los puestos de libros usados en la ciudad de México y descubrí el libro La Güera Rodríguez, de Artemio del Valle-Arizpe, que pinta un cuadro inolvidable—aunque en gran parte ficticio—de este maravilloso personaje. Y cuando escribía mi tesis sobre las mujeres en la Ciudad de México, encontré algunos documentos que la mencionaban. Entre ellos estaba el pleito de divorcio eclesiástico en que su primer marido demandaba una separación, y en 1976 publiqué una selección del largo juicio en mi libro sobre el divorcio eclesiástico.

De modo que la he tenido en mente por muchos años, pero no pudiera haber escrito este libro entonces. Durante los primeros años de mi carrera yo era una historiadora social militante, por lo que estudiaba grupos sociales que habían sido en gran medida invisibles en las narrativas históricas. Nunca hubiera escrito la biografía de un individuo—nada menos de una mujer aristocrática—ni le hubiera dedicado casi la mitad del libro a su recorrido desde la historia al mito. Estos enfoques reflejan cambios que se produjeron en el mundo académico desde finales de la década de los 1980, a saber: lo que llamamos la Nueva Biografía y el Giro Cultural.

Las Nuevas Biografías retratan personas que no eran famosas, muchas veces mujeres; examinan su vida privada además de la pública; y las representan con todos sus defectos en vez de elevarlas al nivel de arquetipo. Y han demostrado lo mucho que podemos aprender sobre la vida diaria tanto como sobre los grandes procesos históricos al estudiar un individuo, especialmente porque la biografía puede combinar la historia social, cultural, política, económica y legal.

El Giro Cultural ha enseñado a los académicos a repensar la historia, no sólo como una colección de hechos, sino como una narración que debemos tratar como un cuento. Y también que deberíamos observar a los propios narradores que cuentan esos cuentos, así como a sus relatos, para obtener una comprensión más completa del pasado. Esa fue la inspiración para la segunda parte del libro que analiza la aparición y diseminación de los datos falsos y cuentos apócrifos que construyeron su leyenda.

Otro factor que influyó en la forma de escribir este libro fue querer llegar a un público más amplio que el que lee una monografía tradicional. He aprendido que cuando los estereotipos persisten en la historiografía, a menudo se debe a que los especialistas sólo se hablan entre ellos. Por ejemplo, en mi libro de 1985 sobre las mujeres de la ciudad de México demostré la falsedad de muchos estereotipos, como de que la mujer tuviera el mismo estatus legal que los menores, lo que no es verdad. Pero ese mensaje no ha alcanzado a bastantes lectores. Espero que una biografía bien escrita, que no sea demasiado larga o complicada, pueda educar al público sin ser pedante. Esa fue mi meta.

Olson: Usted describe a su libro como una meditación sobre la construcción de la historia y las diferencias entre la memoria histórica y la historia. ¿Puede hablar más sobre esto?

Arrom: Lo que he visto en mis años de docencia es que los estudiantes suelen creer todo lo que leen, sobre todo si el profesor lo asigna. Por lo tanto, en mis clases pretendo que los alumnos evalúen lo que están leyendo, preguntando quién lo escribió, cuándo, porqué, en base de qué fuentes, y cómo este contexto pudiera influenciar el argumento. Estas discusiones fueron un factor importante que me llevó a escribir la segunda parte del libro, que examina la política de la memoria.

O sea, que examino cómo la figura de La Güera se transforma constantemente de acuerdo con las ideas de cada narrador sobre el género, la raza, la política y la nación – y según sus fantasías del pasado que hubiera deseado. De modo que el libro tiene un propósito didáctico, porque quiero mostrar al lector cómo separamos los hechos de la ficción, una habilidad muy útil en esta época en que estamos inundados por datos falsos que toman vida propia.

Silvia Arrom dará el discurso presidencial, “Reflexiones sobre una vida en la historia,” en la XVI Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México, Austin. Programa e información: https://xvireunion.utexas.edu/programa/

Entrevista: Madeleine Olson (estudiante de doctorado, UT-Austin)

A Conversation with Dr. Silvia Arrom

Silvia Arrom, Professor Emerita of Latin American Studies at Brandeis University, is the honorary president of the XVI Meeting of International Historians of Mexico (Austin, October 30-November 2). Arrom has had a long and distinguished academic career, publishing widely on Mexican social history, with books including her newest release La Güera Rodriguez: The Life and Legends of a Mexican Independence Heroine (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2021), and numerous other works focusing on women, gender, social welfare, and the poor.[2] She spoke to Madeleine Olson, a UT-Austin graduate student.

Madeleine Olson: The Reunión Internacional de Historiadores de México has been convening for over seventy years across North America—with its first meeting held in Monterrey in 1949. Tell me more about your experience and history with the conference.

Silvia Arrom: The International Meeting of Historians of Mexico was one of the first professional conferences I attended as a newly minted Ph.D. when it was held in Chicago in 1981. Over the years, I have watched the organization grow, become more welcoming to women, and include more social history, reflecting salutary changes in the field. I have been consistently impressed with the variety and high quality of the work on Mexican history.

Olson: The conference theme this year, “Federalisms in the History of Mexico and Mexican Texas,” focuses on how Mexico and its neighbors have attempted to achieve the promises of a united federalism. What are some lessons we, as historians, and primarily social historians, can take from focusing on this subject, and how can we presently apply them?

Arrom: A prominent theme for the republican period of Mexico (1824-1857) is the conflict between federalism and centralism. Historians’ narratives emphasize the weak and fragmentary Mexican state, one that is trying to unite the country but doing so fitfully and not very successfully—one step forward, two steps back. Historians often claim that the Constitution of 1857 and the Reforma solved these problems, and from there on out, the dominant narrative emphasizes the strengthening of the central state and downplays regionalism. What I have learned, especially in studying social welfare, is that we’ve gone too far in that direction. The state was much weaker than we usually assume during the porfiriato (1876-1910) and the post-revolutionary period (1917-onwards). There were, in fact, many regions where it had very little presence.

When we look at how the welfare system worked in practice, it becomes evident that public institutions were few, far between, and woefully inadequate. Private organizations, often religious, stepped in to fill the gap, especially outside major cities. But historians have believed the narrative of the state as the Father of the Poor, with public welfare replacing private charity, and have overlooked the work of private and religious organizations.

Today, when we look at the breakdown of law and order in many regions of Mexico, it becomes clear that the narrative of state consolidation can be misleading. That narrative emphasizes the glass half full, but I believe we need to look at the glass half empty, that is, to recognize the Mexican state’s uneven presence, its absences, and how it worked through local actors. These local actors are critical, as the state has frequently delegated responsibility to them, thus appearing to have a presence in that area. For example, that is how volunteer police forces have worked in many small towns over the past century.

Historians need to study how state actions played out on the bottom, at the local level, in the lives of individuals, instead of focusing on legislation and the upper echelons of government. This will require us to resurrect some of that older narrative of a weak state struggling but not always succeeding in uniting Mexico’s disparate regions and not progressively supplanting the church or private organizations either. In sum, scholars should question the propaganda of the liberal and then the revolutionary state.

Olson: Your newest book, La Güera Rodriguez: The Life and Legends of a Mexican Independence Heroine, covers the federalist period in Mexico and tracks not only the life of the fabled heroine, María Ignacia Rodríguez de Velasco, but also the use of her story in Mexican lore after her death. What was her experience during the Independencia and her hope for the future of Mexico?

Arrom: My book on La Güera (as she was usually called because she was very fair) explores both her life and her afterlife in Mexican arts and letters. During her lifetime she was known as a beautiful and charming socialite. However, only in the mid-twentieth century did she become an independence heroine, one of the many myths circulating about her.

She was not, in fact, a major heroine. She never came out publicly in favor of independence and she was never tried or punished as an insurgent, as many women were. We have very few of her private letters either. So we don’t have many documents that show her political convictions or her hopes for the future of Mexico.

We do know that in 1808 she was part of a criollo group centered around the Mexico City ayuntamiento (city council) that favored provisional self-government until the French invaders left Spain and the rightful king, Fernando VII, could return to the throne. This group wanted autonomy but not yet a break from the mother country. In 1809—a full year before the Grito de Dolores—La Güera was involved in a conspiracy against the leader of the Yermo Coup that had squelched that project, and she was banished from Mexico City for a few months and exiled to Querétaro. The very detailed files on this incident do not mention any link to the independence movement. They only say that the intrigue was based on personal resentments and that, by spreading too many rumors, La Güera was exacerbating tensions in the capital city. She thus appears to have been a critical node in the mouth-to-mouth information network of the time because she was a great gossip and very sociable.

After she returned to Mexico City, she was careful to maintain a low profile. After all, as a widow with five children, she couldn’t risk another punishment. However, we do know that on at least one occasion she gave some money to the rebels who occupied her valuable haciendas, probably to buy protection for those properties rather than out of sympathy for the cause. In vain, because the rebels left the estates in ruins and she lost her main source of income.

Her story represents, I believe, that of many Mexicans who experienced the war years as a time of crisis and economic insecurity, who were unsure of what position to take, and who tried to play all sides in order to protect themselves and their families above all. This narrative contrasts with the story that historians like to tell about the independence period because it is not clear-cut, but a story of ambivalence, vacillation, and suffering. It is not the standard triumphalist story but much more complicated.

It was only in 1949, when Artemio de Valle-Arizpe wrote a historical novel about her, that she was catapulted back into public consciousness. By inventing many facts and manipulating others, he created the myth of La Güera as an intrepid heroine and sex pot who had affairs with the leading men of the independence period. So appealing was his story that it has been endlessly repeated—and embellished—to create the legendary figure of a strong, liberated woman who was also a bold patriot.

Olson: You talk about how this book has been in the making for nearly half a century. How has the research process changed throughout your career and in relation to your evolving understanding of the role of social history in the academy?

Arrom: I first met La Güera as an undergraduate when I read Fanny Calderón de la Barca’s lively travel account, Life in Mexico. This book changed my life. I was always interested in Latin America because my parents were Cuban. This book made me a Mexicanist and opened my eyes to social history. At a time when my courses emphasized political and military events, with a smattering of economic and intellectual history, Life in Mexico included women and the family, the poor, and social relations. In retrospect, I realize that I’ve devoted my entire career to studying those subjects, in the same place and time as Fanny’s book.

Then, as a graduate student wandering the used book stalls in Mexico City, I found a battered copy of Artemio de Valle-Arizpe’s book, La Güera Rodriguez, which paints an unforgettable—though I now know largely fictional—portrait of this marvelous personage. In doing my dissertation on women in Mexico City I found several documents about her, including the fascinating judicial records of her first husband’s suit for a separation, and I published an excerpt of that case in 1976, in my book on ecclesiastical divorce.

So she’s been at the back of my mind for a long time. But I could not have written this book until recently. During my early career, I was a militant social historian who studied groups of people who were largely invisible in the historical record. I would never have written the biography of one individual—let alone an aristocratic lady—nor would I have devoted nearly half my book to tracing her posthumous journey from history to myth. These approaches reflect changes in the field beginning in the late 1980s, namely the emergence of the New Biography and the Cultural Turn.

The New Biographies study less famous people, often women; examine their private as well as public lives; and portray them warts and all, rather than elevating them into archetypes. And they have shown how much you can learn about daily life as well as big historical processes by studying an individual, especially because biographies can combine political, economic, cultural, and legal as well as social history.

The Cultural Turn led scholars to think about history not just as a collection of facts but as a narrative that we should treat as a story. And it showed that we need to study the historians telling the stories as well as the stories themselves to gain a fuller understanding of the past. This was the inspiration for the second part of my book that analyzed the emergence and dissemination of the false facts and apocryphal stories that made her a legend.

Another factor that influenced how I wrote this book was that I wanted to reach a broader audience beyond the scholars who read traditional monographs. I have found that stereotypes about the past often persist because specialists are mainly talking to one another. For instance, I challenged many stereotypes in my 1985 book The Women of Mexico City, such as that women had the same legal status as minors, which I showed was not true. But that message didn’t reach enough readers. I hope that a well-written biography, if it’s not too long and complicated, can educate the public without being terribly pedantic. That was my goal.

Olson: You describe your book as a meditation on the construction of history and on the differences between historical memory versus history. Can you talk more about that?

Arrom: In my decades of teaching I’ve learned that many students believe everything they read, especially if the professor assigns it. However, in my classes I try to get students to evaluate each text by asking who wrote it, when, why, and on the basis of what sources, and to consider how this context might shape the argument. These class discussions were a major factor that led me to write the last part of my book, which examines the politics of memory.

In other words, I study how La Güera’s story is constantly reworked to fit the present, according to each author’s views of gender, race, politics, and nation, and according to their fantasies about the past they wished had existed. The book thus has a didactic purpose, to show the reader how we can separate fact from fiction—a very useful skill in this age when we are bombarded by “fake facts” that take on a life of their own.

Silvia Arrom will deliver the presidential address, “Reflexiones sobre una vida en la historia,” at the XVI International Meeting of Historians of Mexico, Austin. Program and information: https://xvireunion.utexas.edu/programa/

Interview: Madeleine Olson (Ph.D. student, UT-Austin)

[1] https://brandeis.academia.edu/SilviaArrom

[2] https://brandeis.academia.edu/SilviaArrom

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.