In The Global Interior, Megan Black uses the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) controversial history to examine how the U. S. government wielded political and economic power to access natural resources in the American West and influence international policy. The book’s title illustrates the irony of a department responsible for internal affairs being involved in foreign policy. Covering the Department of the Interior’s evolution over the course of two centuries, Megan Black examines its effectively colonial approach to securing access to resources and expanding U. S. power, from the occupation of the American West to the recent use of technologies such as Landsat satellites to map resources and open them to private American companies.

Created in 1849, the Department of the Interior’s initial objective was the development of the American West. In the wake of military-led expansion, control over territory passed into the civilian hands of the Interior, creating a benevolent cover-up that concealed a colonial enterprise. The Department of the Interior assisted in the colonization of territory expropriated after the Mexican-American War and facilitated the expansion of capitalism into Indigenous lands. However, the closing of the Western frontier in the 1890s forced the Interior to expand its activities overseas under the guise of national security and based on the colonial framework. Hence, the activities of the Interior supported cooperation with developing countries to trade and extract minerals essential to American industry during the 20th century. For instance, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy in the 1930s established relationships with Latin America in part through cooperative mineral ventures and land-use planning. The Department of Interior’s procedures for exploiting resources were replicated by the United States in Latin America, the Philippines, Japan, and other sites around the world.

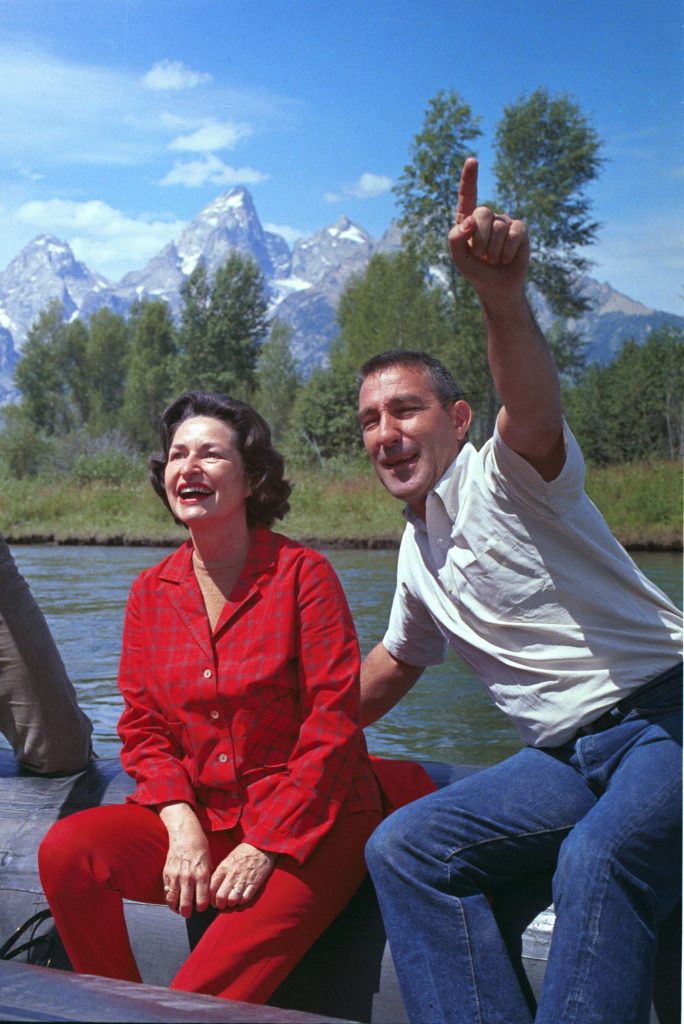

Black analyzes both the hard and soft edges of Interior’s global strategy. The Department simultaneously supported the exploitation of natural resources and nature conservation programs, providing intelligence about natural resources in a way that would benefit US commercial exploitation. In the mid-1960s, Stewart Udall, a DOI official, promoted multiple conservation programs across Latin America while offering technical support to foreign governments interested in developing their mineral economies. Subsequent decades saw the Department of the Interior extend US influence into the developing world’s agricultural sector since modern farming depends on mineral fertilizers like phosphorus and nitrogen.

Due to the geographical scale of its influence, the Department of the Interior’s work was often accomplished through support for private economic activity. However, President Reagan’s deregulation policies in the 1980s also had an impact on the Interior’s funding. Stigmatized as a costly middleman, Interior had to reduce its role. At this point (and towards the end of the book), Black turns her narrative back towards the heartland of the United States to examine an unusual organization: the self-styled “Indigenous OPEC.” Black shows how the Interior’s retreat and the emergence of a market system in its place led Indigenous communities to organize themselves as capitalist institutions in dialogue with private companies. Curiously, the wastelands allocated to Indigenous people by the Interior ended up being rich in minerals, including oil.

Using the tools of environmental history, The Global Interior contributes to debates about environmental politics and international relations, demonstrating the intricacies of cooperation and unilateralist policies. The Global Interior draws a connection between mineral policy, varying forms of colonialism, and international conservation. The book argues that U. S. environmental policies are designed to accrue economic benefits and ensure access to natural resources around the world. Black highlights the tension between environmentalism and economic production.

Daniel Silva is a Ph.D. student in Geography and Environment at the University of Texas at Austin. He conducts research on land use change, environmental policy, and agricultural economics. Co-authored policy briefs and papers with a focus on the Brazilian Amazon and the Cerrado biome.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.