by Ben Weiss

Robert Allen’s The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective constitutes an impressively holistic approach in economic history to a topic that can be infinitely multifaceted and is often severely oversimplified. Considering that the causes of British industrialization have been the subject of heavy debate for the better part of a century, if not longer, Allen offers a refreshing infusion of nuance to classic questions in European and global economic history. He provides a well-rounded account of why Britain industrialized without becoming either too technical or too simplistic in its dialogue with other economic explanations.

Robert Allen’s The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective constitutes an impressively holistic approach in economic history to a topic that can be infinitely multifaceted and is often severely oversimplified. Considering that the causes of British industrialization have been the subject of heavy debate for the better part of a century, if not longer, Allen offers a refreshing infusion of nuance to classic questions in European and global economic history. He provides a well-rounded account of why Britain industrialized without becoming either too technical or too simplistic in its dialogue with other economic explanations.

Allen argues that industrialization occurred in Britain because institutionalized labor costs were comparatively higher there than in other places in the world. The use of coal to provide energy to its burgeoning commercial centers was associated with costs that were drastically lower than those of other industrial contenders. Healthy wages engendered a comparatively well-educated class of laborers, which also helped generate significant technological innovation and investment. Allen contends that his combination of advanced labor and cheaper energy not only explains why the industrial revolution began in Britain, but also why it had to occur there.

Throughout the book, Allen refutes earlier arguments that see science, the Enlightenment, politics, demographic shifts, agricultural movements, and numerous other issues as the singular key factors in industrialization. His discussions of each of these alternate explanations for the industrial revolution systematically detaches, or at least makes an effort to detach, strict causality from each. For many of these accounts, such as the role of agricultural, technology, and population change, he is able to avoid direct confrontation with scholars in his field by incorporating their arguments into his own interpretations of the importance of wage labor and the pursuit of economic opportunity.

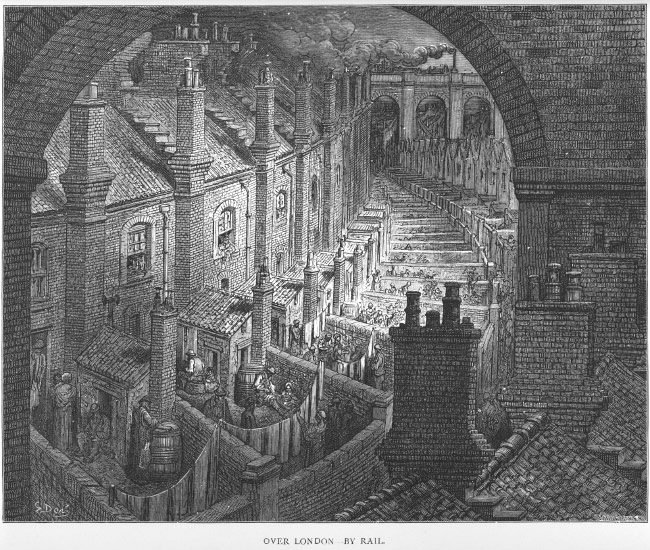

Philip James de Loutherbourg’s “Coalbrookdale by Night,” which depicts the Madeley Wood Furnaces (Science Museum, London)

While a few of Allen’s comparisons and data may require more interrogation from the arena of political and cultural history, his attempt to cover as many counterarguments as possible features valiantly throughout the work. Most impressive for an economic history is the way in which domestic British cultural evolution is meticulously addressed. For example, Allen carefully examines the qualitative influence of shifts in agriculture, technology, and literacy rates on generating a willingness to engage in the social and economic opportunities created by energy and labor circumstances in Britain.

Allen’s book will prove a helpful introduction to the traditional literature of industrialization. Though its argument, which is deeply rooted in economic methodology, may be insufficient for readers who desire substantial political and social explanations, its comprehensiveness in the arena of economic history is admirable. Most importantly, Allen does well to seat his analysis in the current scholarly emphasis on globalization, and in the case of economic history, the global dimensions of commerce. These dimensions help Allen situate the rise of Britain as a core financial power with complicated connections to the global peripheries. Fundamentally, The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective delivers a refreshing account of an old narrative in industrial economic history.

More on British history:

Robin Metcalfe on the history of London’s meat market

And Jack Loveridge’s review of The Decline, Revival and Fall of the British Empire