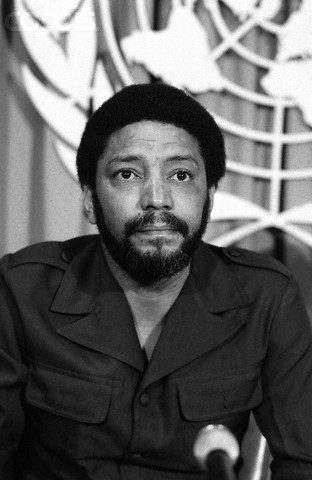

On October 19, 1983, members of Grenada’s People’s Revolutionary Army assassinated Prime Minister Maurice Bishop of Grenada and seven of his associates, triggering the sequence of events that led to the sudden end of the Grenada Revolution. With the prime minister dead, the hastily established ruling military council unsuccessfully attempted to restore order to stave off the military invasion being planned in Washington, D.C. But just days after Bishop’s death, President Ronald Reagan launched Operation  Urgent Fury to save American lives and ostensibly restore democracy to the island of Grenada. Having established their authority, U.S. military officials rounded up the leadership of Grenada’s socialist party, the New Jewel Movement, and the army high command, whom the Grenadian people and the U.S. blamed for the murders. Later known as the Grenada 17, these men and women would be tried, convicted, and sentenced to hang for the deaths of Bishop and his compatriots, despite a lack of credible evidence linking them directly to the assassinations.

Urgent Fury to save American lives and ostensibly restore democracy to the island of Grenada. Having established their authority, U.S. military officials rounded up the leadership of Grenada’s socialist party, the New Jewel Movement, and the army high command, whom the Grenadian people and the U.S. blamed for the murders. Later known as the Grenada 17, these men and women would be tried, convicted, and sentenced to hang for the deaths of Bishop and his compatriots, despite a lack of credible evidence linking them directly to the assassinations.

In Omens of Adversity, Caribbean anthropologist David Scott wrestles with the connection between time and tragedy, engendered by what the Grenadian people experienced as the catastrophic collapse of the popular movement as they lived on in the post-socialist moment. In the wake of the assassinations and the U.S. intervention, Grenadians who came of age during the revolution and watched its ruin found themselves “stranded” in the present, bereft of hope for the future, and grieved they had to be rescued by the United States, whose power the New Jewel Movement had set out to challenge. Adding insult to injury, the U.S. played a role in the disappearance of the bodies of Bishop and the others, robbing the families of the deceased and the entire revolutionary generation of a chance to mourn the prime minister and the future free of Western hegemony he had embodied. In assessing the socialist experiment in Grenada and its end, Scott argues that although the Grenada Revolution is often forgotten, it is nevertheless a key event in the world history of revolutions because it signaled an end to the possibility of post-colonial socialist revolution and the ascendancy of Western neo-liberalism.

Traditionally, scholars of liberal political change see trials such as that of the Grenada 17 as markers that signify the transition from the illegitimate old regime to the new transparent liberal order. However, despite the apparent triumph of the Western tradition, the transition to liberal democracy has had its flaws. Using the trial of the Grenada 17 and its aftermath, Scott raises questions about truth, justice, and democratic transitions. The investigation and trial were full of irregularities, including the torture of the defendants. Scott emphasizes that instead of an earnest attempt to secure information and justice, the goal of the 1986 prosecution of the Grenada 17 was to criminalize the NJM leadership and their political ideology. He describes the proceedings as a late Cold War “show trial” crafted to demonstrate what happened to those in America’s “backyard” who sought revolutionary socialist or communist self-determination. Instead of indicting the 17, Scott reframes them as “leftovers from a former future stranded in the present.”

Members of the Eastern Caribbean Defense Force participate in Operation Urgent Fury (Wikimedia Commons)

Although the jury found the Grenada 17 guilty, the anomalies in the investigation and trial meant that the Grenadian people still had questions about what happened and why. Public interest was aroused when a group of high school boys began investigating the disappearance of the victims’ bodies. A truth and reconciliation commission was constituted and began to research the events of October 19 in late 2001. However, these efforts were tainted, too. The report recapitulated the standard narrative of the events, complete with anti-communist biases that demonized the NJM – unsurprising in light of the commissioners’ refusal to meet with the Grenada 17. However, Scott’s reading of the report’s appendices containing statements from NJM leadership shows that a different story could have been told. Unfortunately, it seems unlikely that the people of Grenada will ever know the full truth about what happened to Maurice Bishop and the others. After all, in the neoliberal era, the socialist past can only be a criminal one.

You may also like Lauren Hammond’s reviews of Tropical Zion: General Trujillo, FDR, and the Jews of Sosúa and The Dictator’s Seduction: Politics and the Popular Imagination in the Era of Trujillo