Kacey Manlove

Rockport Fulton High School

Senior Division

Historical Paper

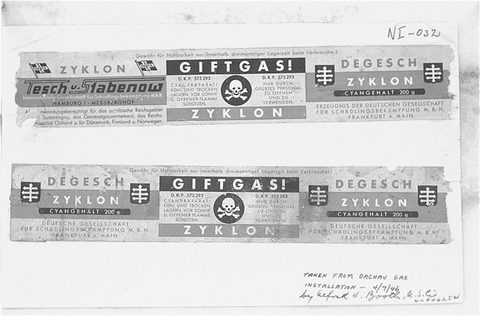

Nazi Germany was not only responsible for death and violence across Europe. The Third Reich also enslaved millions in their factories. In particular, the German industrial giant I.G. Farben, which produced the Zyklon B that murdered so many during the holocaust, enslaved thousands in order to make its deadly products. But after the war’s conclusion, Norbert Wollheim, formerly an enslaved laborer for I.G. Farben, demanded reparations–both financial and moral–for his country’s use of slavery.

Kacey Manlove, a student at Rockport Fulton High School, wrote a research paper for Texas History Day that tells Wollheim’s remarkable story. You can read two excerpts below and open the full paper above.

By the time World War II began on September 1, 1939, Hitler had already annexed Austria and the Sudetenland, and his army then rapidly advanced through Europe, implementing Anti-Semitic laws and creating pools of available laborers. Farben followed the German army to lay claim to chemical industries in annexed or conquered countries, increasing its holdings and profits five-fold to become the largest chemical company in the world. Hitler’s Reich exclusively utilized Farben’s fuel for armament, its chemicals for medical experiments, and its Zyklon B pesticide for executing prisoners incapable of work. By November 1940, Farben’s quota for synthetic rubber (buna) exceeded what its plants could produce. To satisfy the Reich’s needs, Farben agreed to quickly build two new plants, one an extension of their current plant in Ludwigshaften, Germany, the other in Auschwitz, Poland, home of the Nazi’s largest concentration camp system (appendix D). Farben officials specifically selected the Auschwitz location to use raw materials from the nearby Furstengrube coal mines for energy and existing railways for easy shipping. The Auschwitz camp system also provided access to prisoners whom Farben utilized for slave labor in exchange for a nominal payment to the Schutzstaffel [SS]. Slave laborers built Buna/Monowitz, the first industry-based concentration camp, to accommodate Farben’s needs (appendix E), and by 1945, Farben utilized more than 100,000 slave laborers in its various plants. Nazi Labor General Fritz Sauckel authorized Farben’s employees to exploit prisoners “to the highest possible extent at the lowest conceivable degree of expenditure.” After the war, this policy would become the core principle in Norbert Wollheim’s suit against Farben for redress.

Labels taken from canisters of Zyklon B from the Dachau gas chambers (USHMM, courtesy of National Archives)

Norbert Wollheim’s suit and subsequent agreement with German industrial giant I. G. Farben not only reclaimed rights for survivors in Buna/Monowitz but also set a precedent for toppling other German industry giants that had used slave laborers to support Nazi Germany. Governments of both America and the Federal Republic of Germany played critical roles in concluding the reparations process that the Wollheim Agreement had begun. All German firms stipulated that their settlements represented a moral obligation, not an admission of any legal responsibility, but to former slave laborers, the monetary redress they received provided a sense of closure, exemplifying the justice they had been denied at Nuremberg. Against great odds, Wollheim’s civil suit had cast the first stone, defeating an industrial giant. The ripple effect caused by that defeat paved the way for additional settlements that have compensated over 1.6 million former slave laborers for their loss of rights during one of the greatest human rights violations in the twentieth century.

Check out the latest Texas History Day projects at Not Even Past:

O Henry Middle School student Maura Goetzel’s paper on liberty and security in early America

And a group of Westwood High School students’s website on America’s most dangerous moment