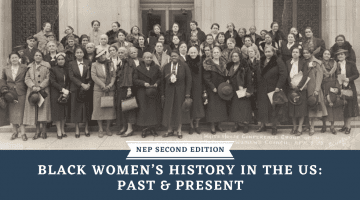

From the editors: To mark Women’s History Month, we collected a range of Not Even Past articles and reviews and assembled them here, on a single page devoted to resources on women’s history. We’ve organized our content around seven topics. The articles grouped under each topic heading highlight groundbreaking research. However, they are also intended […]