By Sandy Chang

On the eleventh floor of the National Library of Singapore, I sit with a pile of large, gray boxes stacked high on a trolley. I am hoping to be transported to the island’s past. The boxes are filled with legal documents from the British colonial era, mainly affidavits, writs of summons, bills of costs, and occasionally testimonies from witnesses in the Straits Settlements. The pages are sepia-colored, some speckled with mold – a reminder of the gulf of time that separates me from the people who produced these very documents I now hold in my hands. To be a historian is almost always to be cognizant of the passage of time and the changes that accompany it.

For historians, archives are portals into the past. They offer tantalizing, if partial, glimpses of a different era; snapshots of those who inhabited a world different from our own. Engaging with primary sources, in the words of historian James Warren, entails the experience of “’passing over’…a crossing over to the standpoint of another culture, another way of life, another human being” and to return with a deeper understanding of the past. Of course, historians know that our sources are not unmediated versions of history nor do they contain self-evident truths about the lived experiences of others. Nonetheless, we search longingly for that one document, one photograph, or one artifact that we hope will bring us closer, back in time, to the worlds we study.

The papers I rifle through are part of the Koh Seow Chuan Collection, named after its donor, a retired Singaporean architect. Koh was one of the founders of DP Architects, a company responsible for the design of the famous Esplanade Theaters by Marina Bay. He also happened to be an avid collector of stamps, art, and historical artifacts. In 2009, he donated 1,714 heritage items to the National Library Board of Singapore, consisting of rare maps and photographs, old letters and envelopes, and legal documents dating back to the early nineteenth century. The legal documents in Koh’s personal collection include records from the Straits Settlements Supreme Courts and District Courts, filling over four hundred boxes. In them, historians can locate the records of many prominent members of the Straits Chinese community, including Lim Boon Keng, Lim Nee Soon, and others.

I am, however, using these documents to search for traces of Chinese migrant women who sailed across the South Seas and settled in British Malaya in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Far from the thrilling adventure I had anticipated, the process feels tediously dull. Combing through the dense law cases and reading the highly formulaic legal rhetoric for evidence of migrant women can feel like searching for a needle in a haystack. In the first week, I encountered a gamut of historical characters: planters and traders, merchants and bankers, manufacturers and small shopkeepers, pineapple preservers and cake-makers. While some of their stories offered delightful anecdotes, I could not help but notice the absence of women. It made me wonder, were these documents appropriate sources for my research or did I need to change the questions I was asking altogether?

With time and patience, the women in these documents gradually became visible to me. At first, their appearances were elusive: a woman sued by her father-in-law for jewelry; a sister embroiled in a legal battle with her half-brother over the administration of their father’s estate; and six women petitioning the court to be legally recognized as the wives of one Chinese man. These were exciting discoveries, but I was baffled by how I would piece together these scraps to construct a coherent narrative of the past. How could I make sense of the “smallness” of these stories within the broader context of a rapidly changing regional maritime economy and of Chinese labor migrations into and around the British Empire in Asia?

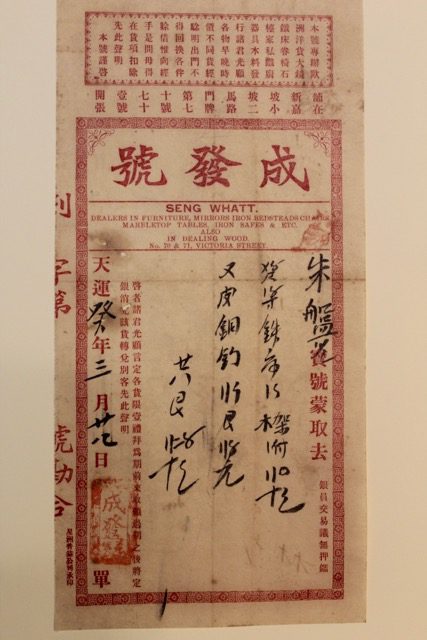

Bill of goods; transaction between a trader and opium shopkeeper, 1913 (via Koh Seow Chuan Collection, National Library, Singapore).

The fragments of these women’s stories emerged slowly, but collectively they gathered momentum. A marked pattern became clear: women almost never appeared in colonial Supreme Court records, either as plaintiffs or defendants, unless they were widows. Of course, the colonial records of the Police or District Courts in the Straits Settlements tell a different story. But, in the colonial Supreme Court, women were first and foremost recognized by the state as conjugal subjects. In case after case, the marital statuses of Chinese women were meticulously recorded: “married woman,” “widow,” or “spinster.” Not all women, however, had equal access to legal recourse via the Supreme Court. Lengthy legal battles, expensive civil litigations, and the practical challenges of serving writs of summons to individuals in a highly transient and mobile colonial society meant that only the very wealthy could take their disputes to court. As such, the women in these records were almost always propertied individuals with substantial wealth.

Chinese Lady-in-Waiting Attending to Her Chinese Mistress’ Hair, c.1880s (Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore).

In Koh Seow Chuan collection, I encountered widows who appealed to the colonial state for maintenance; others who sued for outstanding debts owed to their husbands; some who battled one another for the distribution of the family estate. Their stories reveal a fascinating and complicated relationship between conjugality and wealth, gender and colonial law. Collectively, they demonstrate how migrant Chinese women increasingly utilized colonial legal institutions as one way of resolving transnational family disputes concerning inheritance, succession, and property rights. At the same time, their stories also shed light on their vulnerability within the colonial legal process itself – a process that was in many ways arbitrary and precarious.

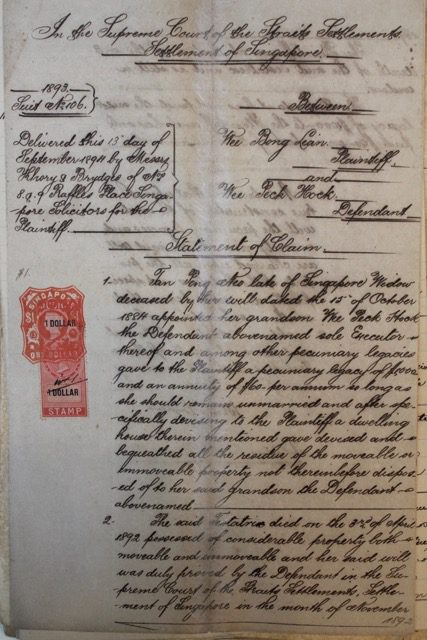

Statement of claim by a Chinese widow, 1893 (via Koh Seow Chuan Collection National Library Singapore).

Historians often dream of finding that one treasure trove that will unveil the secrets of the past; that one document from which we could write a whole chapter. Sometimes, we are given four hundred boxes instead. Their contents, which at first appear to be “run-of-the-mill,” require us to scour through them carefully. Only then does the past come momentarily into focus. In the digital age, we are often tempted to shuffle through our sources quickly for relevant finds and discard those that don’t “fit” the scope of our research; there’s a temptation to photograph first and read later. But, practicing patience in the archives and learning to sit still with the sources we are given can yield surprising rewards. It enables us to “pass over” to the other side and to see patterns that arise only when we attend to both the absence and presence of women’s lives in the colonial legal archive.

![]()

You may also like:

History faculty recommend Great Books on Women’s History: Crossing Borders.

Isabel Huacuja reviews The Forgotten Armies: The Fall of British Asia, 1941-1945 by Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper (2006).

Mark Lawrence discusses a CIA Study: “Consequences to the US of Communist Domination of Mainland Southeast Asia,” October 13, 1950.

![]()