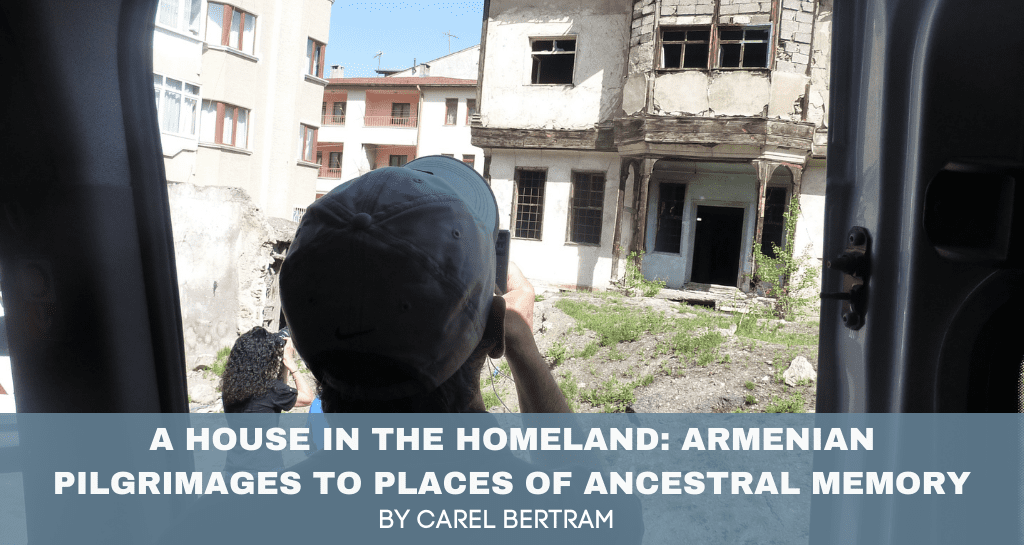

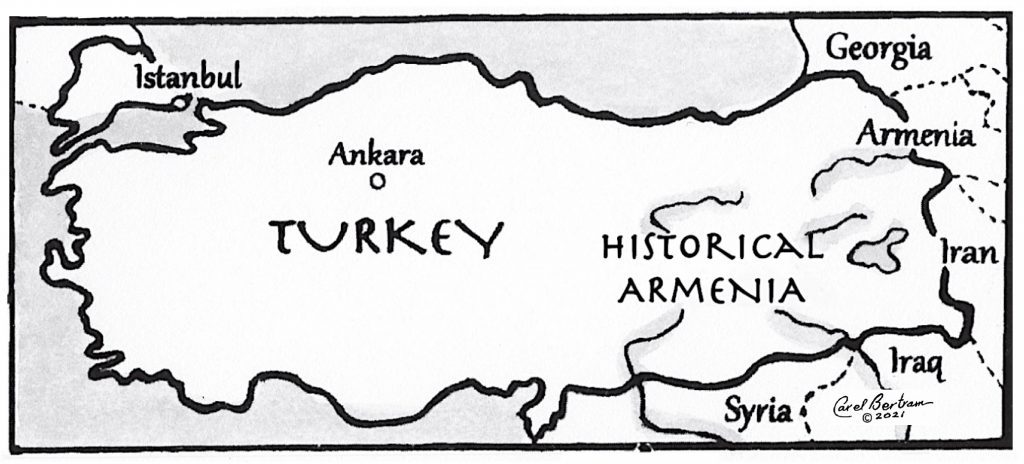

Between 2007 and 2015, I traveled with small groups of Armenians from the diaspora who were “returning” to a place they had never been. Each one was seeking the hometown or village lost to their own parents or grandparents who had survived the Armenian genocide of 1915. And so, although we were traveling mostly in the east of modern Turkey, it was “Historical Armenia,” their lost Ottoman Armenian homeland that they saw outside the windows of their mini-buses.

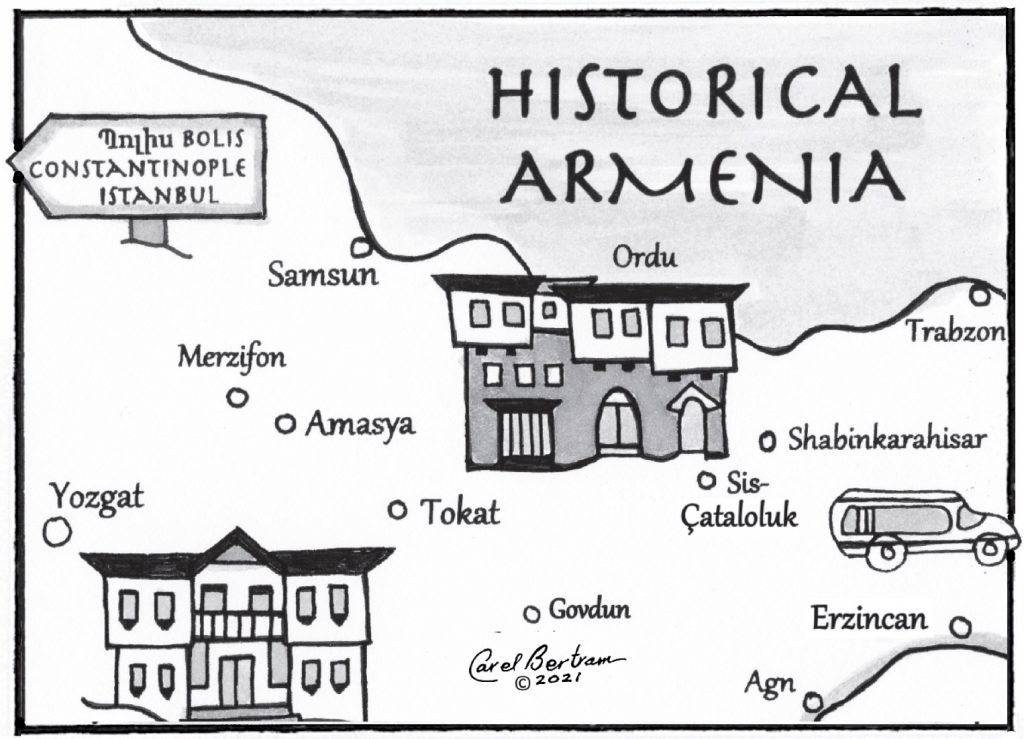

From the map of Historical Armenia traveled by pilgrims, in House in the Homeland ©Carel Bertram

For the most part, these “return travels” have been led by Armen Aroyan, who dedicated his life to this difficult quest, and whose help was sorely needed. Driving through eastern Turkey, he could lead us on unmarked and unpaved roads, and following his own knowledge or instincts, could find villages now emptied of Armenians, possibly emptied of any architectural remains at all, and whose names had been changed to erase their Armenian past.

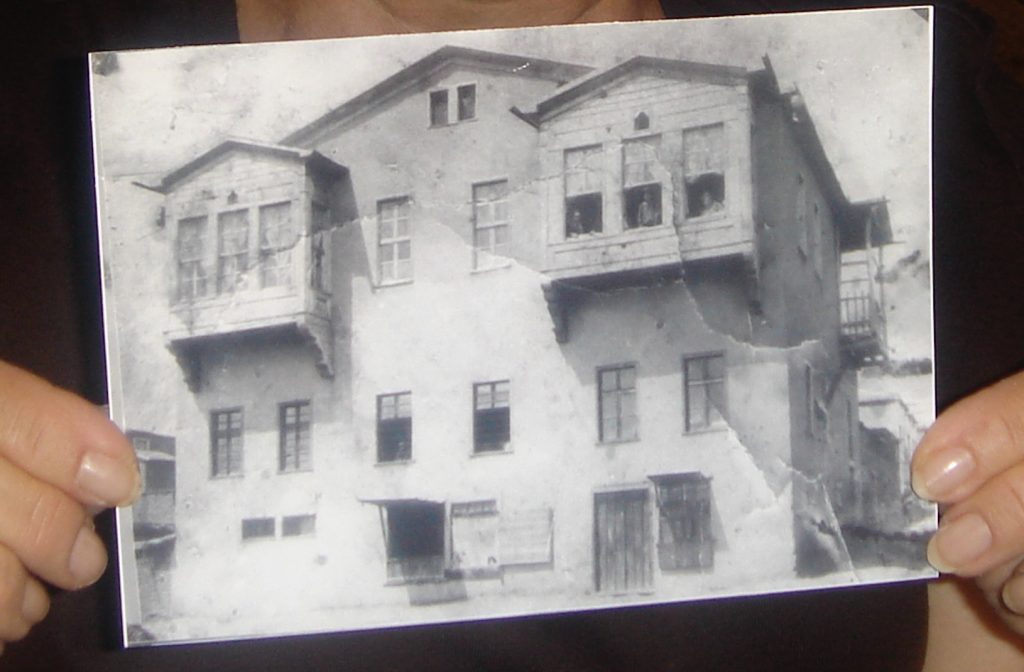

Together with some few precious hand-drawn maps used to locate former houses, these travelers carried luggage filled with “survivor items”: photographs, title deeds, insurance receipts, and letters sent from a lost place in the “before time.” One traveler, Mary Ann, brought a copy of a 1911 painting of her ancestral town of Yozgat made from memory by her great uncle who had left for Philadelphia in 1910. I used it as the cover for my book.

Each of these items had a story to tell and a claim to make. But most of all, these travelers carried stories, ones they had heard from their older family members about this place, making their attachments especially profound. For them, their own town or village represented “the homeland,” and if they found it, they hoped to find their ancestral house, which they considered its beating heart.

Because all were seeking spiritual solace, most called these journeys pilgrimages, and referred to themselves as pilgrims. Having traveled with them, I do, too. The result of my journeys with them is A House in the Homeland, Armenian Pilgrimages to Places of Ancestral Memory, (Stanford University Press), which shows the many ways by which they created a pilgrim’s reward. Grounded in an ethnographic methodology, A House in the Homeland is based on a unique archive and a compelling theoretical structure with its own vocabulary and poetic vision. Fittingly, its publication date coincides with April 24th, the day set aside to commemorate the Armenian Genocide.

An Ethnographic Methodology and a Unique Archive

I travelled on over a dozen pilgrimages to “Historical Armenia” with Armen Aroyan and thus watched well over 100 individuals experience their homeland towns and villages. Some actually found their houses, but many found only a fragment – a gate, foundations, a tree or a fountain, or even the house’s footprint.

Two cousins, Bob and Steve, did not have sufficient clues to find their ancestral house in the town of Yozgat, but an ethnographic museum in a historically Armenian neighborhood worked as a proxy. It seemed close to the descriptions that they had heard about it, and its status as a museum meant they could enter. Inside, in a room that had no guard, they hid a photo of the family who had escaped several years after the genocide. The museum held no information about any Armenian connection.

Pilgrims on other trips did the same thing, but I could not understand these actions fully just by watching or, as it turned out, by their telling me that they “had brought their families home.” Spending at least ten days with each pilgrim group allowed for many conversations as well as a building of trust. But what allowed my ethnography to be so productively granular was the sustained conversations that followed, many still ongoing, and many leading to permanent friendships. While working on A House in the Homeland, I could make phone calls or send texts or emails to many pilgrims, including the cousins, Bob and Steve, as I tried to untangle and contextualize the story behind their transgressive act.

Over time, Bob and Steve sent me a variety of materials, but only in later conversations did I learn that they owned an unpublished oral history of their survivor uncle Avedis, one of the relatives who had finally escaped from Yozgat. On reading it, I found it to reveal an astonishing family history that became a full chapter in my book, for it made clear that their poignant act, while seemingly so similar to others who had sequestered secret photos, pointed to a distinctive meaning that served their individual spiritual needs. Only my large archive of pilgrim experiences allowed for such similarities to emerge, and only its depth allowed these to be evaluated in the context of the pilgrims’ memory stories, which is what these photos represented.

An archive of this size holds a lot of stories, but I was able to enlarge it even further by adding the experiences of several hundred other pilgrims with whom I had not traveled. This was done through their descriptive books, journals, memoirs, blogs, letters, and creative works. Many of these travelers were among the several thousand pilgrims who had traveled with Armen Aroyan over the years, and my information about them includes some of the videos he took of their pilgrimages, now housed at the University of Southern California’s Institute of Armenian Studies. Important, too, were the articles that they sent him for his collection of pilgrim experiences, The Pilgrim Speaks, which is currently unpublished. Furthermore, I was able to contact many of these people who often became important pen-pal informants, some even friends, widening the breadth and deepening my stratified archive’s record of individual, shared and communal memory and sensibilities.

Some of these materials document pilgrimages that predate these contemporary trips. In A House in the Homeland, I also analyze the journeys of actual survivors, whom I term “natives”– to separate them from the “descendants,” the children and grandchildren who form the central part of my observations and insights. Although the survivors who wrote these pilgrimage memoirs were gone, I was able to speak with many of their children. Thus, this archive documents the affective reach of homeland for two dispossessed cohorts, one just before and one closely following its loss.

Memory, Memory-Stories, Assembled and Re-assembled Memory

The houses that descendant pilgrims searched for evoked all the emotions held by exiles forced from home: warmth, wholeness, fear, trauma and rage. But what drove the urge to find them was memory. Yet it was clear, almost by definition, that a memory of their houses or of the genocide was only applicable for the earliest pilgrims, those native pilgrims who had once lived in those houses. By having information from both groups, however, I was able to construct a new category of memory that differentiated pilgrims who were the direct descendants of these survivors from the survivors themselves. I term this descendant category memory-stories because the memories these descendants brought with them were stories that they remembered hearing from their relatives from the survivor generation. Furthermore, because the descendant pilgrims themselves had no firsthand memories of the houses and places they sought, the emotional burden ascribed to those lost houses was in large part a resonance of the pilgrims’ emotional attachment to these survivor family members. Additionally, these stories, told and heard in the diasporic host-land, which, in this study was usually the United States, meant that these memory-stories were as place-related as those of the survivor generation; but rather than being linked to villages, they were linked to places like Racine, Watertown, Fresno, Glendale, Philadelphia, and New York City. Most critically, then, this approach addresses both survivor memory and descendant memory-stories as wholly autobiographical, bringing to light how the autobiographical content of the descendants’ memory is always in construct with the host-land.

The accumulation of these memory-stories is what makes up what I term each descendant’s “assembled memory,” the affective history of their homeland that they have assembled as their received truths across generations. For Bob and Steve, the memory of their house came from memory-stories from their survivor parents and grandparents that told of how most of their individual families, having perished, lived together in Yozgat for several years after the genocide in relative affluence, but in painfully compromising circumstances that included living as Muslims.

Gesturing to Mircea Eliade’s work on the sacred and Gaston Bachelard’s on the poetic reverie in which memory operates, I suggest that the pilgrims’ memory-stories seem to “erupt” (Eliade would say “irrupt”) into consciousness when pilgrims find their houses, or the places where they must once have been. As these stories activate and then flood their reverie, the place is given a sacred quality as it invites interactions with their elders whose spirits are there, but whose stories they know from the diasporic host-land. It is in this transcendent opening that rituals emerge. For example, on arriving in the southern Anatolian village of Hasanbeyli, Alidz found that memory-stories arose to identify the sacred realm of her house —that “was from my childhood inscribed on my soul,” —through a treasury of stories heard from her grandmother when they lived together in Beirut. This led to a flood of daydreams and reveries:

I’m sitting next to my grandmother

my eyes on her sewing basket and colorful wools

I’m eight years old.

Alidz, led by Armen Aroyan and traveling with her cousins, performed a pilgrimage ritual that I call “communion,” in which they shared a meal and prayers with the spirits of their grandparents at the place where they had lost their past. Having made Hasanbeyli into the village where they shared communion with their family, they returned with a new memory added to the one of violent loss, and softening some of the rage they almost could not bear.

Rituals, then, are one of the ways that, when these memory-stories arrive at the place where they had taken place, the pilgrims’ actions cause memory to be re-assembled.

Bob and Steve’s ritual was the placing of their photo as an ex-voto: an expression of gratitude that their family survived spiritually, able to live again and flourish as Armenians in Pennsylvania. That is, their action was not meant to intervene in the lives of their ancestors, magically allowing them to reclaim the lives they had been denied. Instead, it was meant to impact the meaning —and thus their memory— of place by bringing the history of the house up to date. When the cousins left Yozgat, it was with a feeling of elation, for their house now held the photograph of a healthy, reconstituted family as visual proof of the miracle they had become.

In this way, as pilgrims make their past homes present, A House in the Homeland identifies the many prongs of pilgrims’ agency, but especially as they insert themselves into a positive narrative of the house, which forever more will include their own affective experiences. For some, for example, the ancestral house was identified as theirs by a sudden sign from an elder’s spirit, for some, singing their ancestors’ beloved songs in their ancestral houses made them believe that their ancestors were singing with them. It is these experiences that actuate the re-assembling of memory, for as pilgrims become actors in their house’s narrative, the story includes them, too.

On returning home, the cousins hosted an extended family reunion, with a slide presentation that offered their family an updated Yozgat, now to be imagined and remembered with a particular house that radiated the faces of their Pennsylvania family. It was only by being in Yozgat that the cousins’ memory-stories could activate a transgressive agency capable of intervening in the arc of their homeland history, and one that could be take root in the future.

The Book: A UT Story

The foundation of my work is my archive of over 400 pilgrimage experiences, plus extensive contextualizing historical research. But for the picture of the pilgrims’ engagement to emerge, I would need time to organize my material, compare earlier pilgrimages to what I knew of later ones, and explore my hunches. Fortuitously, I was selected as a Fellow at the Institute for Historical studiers at UT Austin, for the academic year 2013-14. There, under the supportive direction of Seth Garfield, its fellows gathered to further each other’s work on the theme, “Trauma and Social Transformation.” I already had a group of Austin friends and colleagues, as I had been a lecturer, sponsored by UT’s Center for Middle East Studies and the Department of Art and Art History for the three years following the earning of my doctorate in 1999. My dissertation, then unknowingly, had been a preparation for A House in the Homeland, for I had written about vernacular Ottoman architecture, especially those beautiful houses like the ones that Bob and Steve’s Ottoman Armenian merchant families had lived in.

While teaching in Austin, I honed my dissertation into a book that followed how, as the Ottoman empire lost its footing, and Western ideas and concrete apartment houses were taking over the landscape, those beautiful houses began to grow in the Turkish imaginary as an icon of lost Ottoman Turkish values. When I left UT Austin for San Francisco State University, Imagining the Turkish House, Collective Visions of Home was in the good hands of Jim Burr who saw it to publication in 2008 by the University of Texas Press. It was my first effort of tracing the history of the attachment between memory and place.

During my 2013-14 fellowship year in Austin, as I conceptualized A House in the Homeland, it seemed that the Armenian pilgrims I had come to know had much in common with their Turkish counterparts in Imagining the Turkish house. Both were products of the tumultuous end of the Ottoman empire, and for both groups, continuity with traditional values was often rooted in their ancestral houses. But Bob and Steve’s house and the house of every pilgrim who searched for their own, had not been lost to the exigencies of time but to traumatic exile, and to the brutal deaths of their families. Furthermore, modern Turkey had denied Armenians a link to their own history, first by permanent expulsion, second by denying that there had even been a genocide, and third, although this is hard to reconcile with the second, by the nation’s relentless propaganda that branded the pilgrims’ ancestors as traitors to the state, asserting that the Armenians had somehow deserved their fate. Thus, the pilgrims’ houses were at the center of not merely a transformative, but a catastrophic historical experience. A House in the Homeland shows how countering displacement and trauma by poignant performances in their home spaces made their experience part of an affective historical analysis.

Writing about this process for “Not Even Past” brings this journey full circle. Not only are these words of William Faulker, and the title of this monthly offering from UT’s Department of History, apt for many historians, but they are almost prescient to the many like myself who speak to a universal need to bring the past into the present, whether to heal its wounds or to do the hard work of intergenerational continuity. Certainly these words are true for the Armenian pilgrims chronicled in my book: With luggage filled with family documents and photographs, they established a soulful sense of personal ownership of what history had denied them; by performing rituals of their own creation, they animated their houses’ spiritual powers; and by singing its songs and dancing its dances in the places of their origins, they linked their ancestral houses to their host-land homes, where they had learned them and where they will live on. Moreover, by inserting themselves into the origins of their stories, they built new memories into their pasts, and forged new connections for their future. They could not heal the genocide, an impossible quest, but, perhaps, they could create a past they could live with.

Carel Bertram is Professor Emerita in Middle East and Islamic Studies, Dept. of Humanities, San Francisco State University. Her MA in Near Eastern Studies was taken at the University of California at Berkeley, her PhD in Islamic Art History at UCLA. Trained in the visual culture of the Ottoman and post-Ottoman era, she uses art, architecture, cities, literature, ethnography and oral histories to study how we use space and place to represent ourselves in the world; and also how it is that the memory of places creates a particular historical consciousness, especially when remembering a home lost to time or exile.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.