By Tania Sammons

This essay is reproduced from the book we are featuring this month, Slavery and Freedom in Savannah, edited by Daina Ramey Berry and Leslie Harris. If you would like to know more about the book and especially about the sidebars that feature short essays on interesting figures and events related to the Owen-Thomas House and the history of Savannah, you can watch the video interview we posted with the editors.

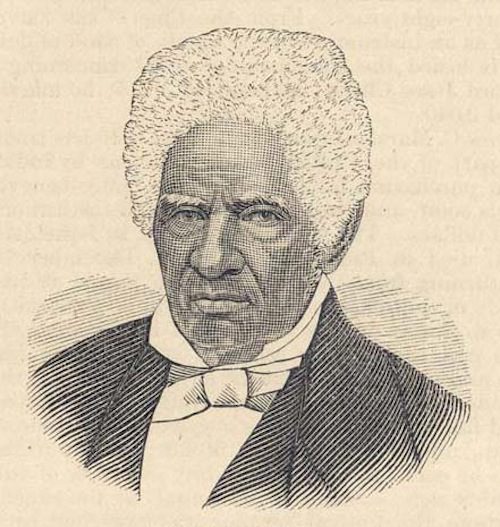

Andrew Cox Marshall was Savannah’s most important African American in the pre-Civil War period. Born into slavery in the mid-eighteenth century, Marshall acquired his freedom and went on to become a successful businessman and an influential religious leader with far-reaching ties throughout Savannah’s diverse free and enslaved African American community; he was also well known among Savannah’s white elite. The lives of those who gained freedom before slavery ended were restricted by laws that limited their economic and social opportunities. Yet Marshall managed to navigate such constraints and achieve some level of success and autonomy.

Andrew C. Marshall. In James M. Simms, The First Colored Baptist Church in North America, Constituted at Savannah, GA, January 20, .D. 1788 With Biographical Sketches of the Pastors (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1888), 76. Courtesy of Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries.

Born in South Carolina around 1755 to an enslaved woman and an English overseer, Marshall wound up in Savannah as a result of two failed manumission promises and ownership by five prominent slaveholders, including John Houstoun, the governor of Georgia in 1778 and 1784, and Joseph Clay, a businessman and judge. Accounts of Marshall’s life indicate he participated in activities that supported the United States in the American Revolution and War of 1812. He purportedly received pay for his work in both wars and had the opportunity to meet General George Washington. Marshall later served as President Washington’s personal servant on his visit to Savannah in 1791. Richard Richardson purchased Marshall in 1812, and Marshall purchased his freedom at some point soon thereafter with funds lent to him by Richardson, who was a merchant, banker, slave trader, and the first owner of the Owens-Thomas House. Richardson became Marshall’s first guardian, which the law required of free blacks. Marshall’s wife, Rachel, and their three daughters—Rose, Amy, and Peggy—had previously gained their freedom through the efforts of Marshall’s uncle, Andrew Bryan, the popular and influential pastor of the First African Baptist Church, as well as Richardson and other white elites in the community. As a free man, Marshall established a home with his family in Yamacraw on Savannah’s west side. He set up a successful drayage (hauling) business that allowed him to accumulate sizeable wealth. In 1824, the tax assessment of his real estate was valued at $8,400, and his will indicates that he had acquired shares in a state bank. At the time of his death, in 1856, he owned several buildings, including a brick house that he left to his immediate family. His fine clothes and silver watch he bequeathed to his enslaved cousin Andrew, showing the strong connections binding the enslaved and the free.

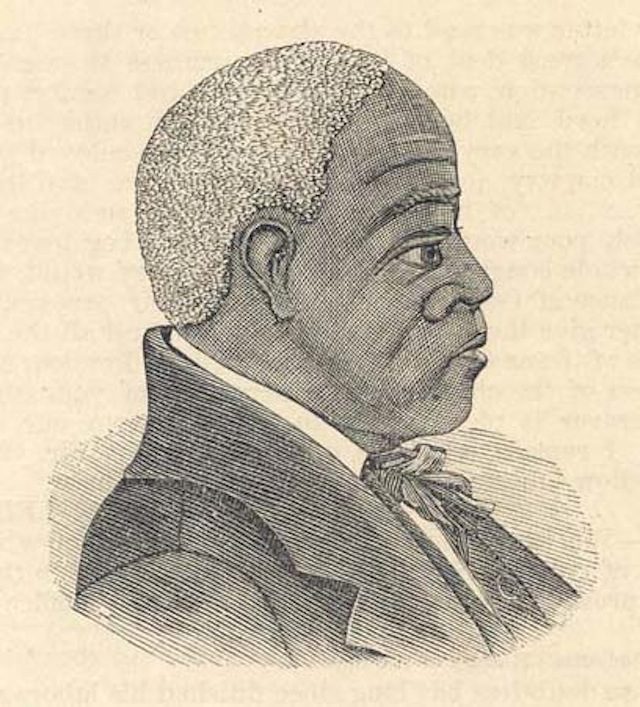

Image of Rev. Andrew Bryan from History of the First African Baptist Church, From its Organization, January 20th, 1788, to July 1st, 1888. Including the Centennial Celebration, Addresses, Sermons, Etc. by E.K. Love

In addition to family, home, and business, Marshall focused his attentions on building up the congregations of black Baptists in Savannah. In 1815, at about the age of sixty, Marshall took over as pastor of the First African Baptist Church. He served in that position twice for a total of more than thirty years. During his leadership, Marshall baptized nearly 3,800 people, converted 4,000, married 2,000. His widespread and diverse religious activity included traveling around the country to preach, taking a special interest in the poor and infirm, and beginning a Sunday school. He even addressed the Georgia legislature. Beginning in 1840, he directed that church funds be used for foreign missions to Liberia, the African country established by Americans for the resettlement of free blacks.

Marshall’s prominent position did not keep him from suffering the indignities visited upon other free or enslaved blacks. He did not always agree with his peers or guardians and was sometimes called out or put in his place. Around 1820 he was sentenced to be publicly whipped for making an illegal purchase of bricks from slaves. His guardian and former master, Richard Richardson, and others spoke in his behalf to ensure the whipping did not “scratch his skin or draw blood.” Nonetheless, the public spectacle was meant to make clear to Marshall and all the free and enslaved people of Savannah the limits of their power.

Within the Baptist association and his own church, Marshall suffered repercussions because of his support of the work of the controversial white minister Alexander Campbell of Virginia, a reformed clergyman who favored the emancipation of slaves. Marshall showed interest in Campbell’s movement, known as the Disciples of Christ, and invited him to speak at the First African Baptist. Marshall’s association with Campbell resulted in a split within the church, with 155 members leaving First African Baptist to establish their own church, Third African Baptist. The Sunbury Baptist Association, the regional Baptist organization run by whites, sought to have Marshall dismissed from his post by the members of his church. When that didn’t work, they removed First African Baptist from their association from 1832 to 1837. The First African Baptist Church was readmitted to the association only after Marshall recanted his support of Campbell and asked forgiveness for his errant ways. In addition, his apology helped ease tensions with the white elites in the community.

Andrew Cox Marshall lived an extraordinary life, not least for reaching the age of one hundred. He experienced slavery and freedom, witnessed and participated in key moments in American history, and spent much of his time helping his fellow men and women. He died in December 1856 after returning home from a preaching tour in Richmond, Virginia, meant in part to raise money to build a new church in Savannah. Hundreds of people attended his funeral. A newspaper account noted “an immense throng without respect to color or condition collected in the Church, the floor, aisles, galleries and even steps and windows of which were densely packed [and] hundreds [were] unable to gain admittance.” He was buried in a family vault at Laurel Grove South Cemetery.

Tania Sammons is senior curator for decorative arts and historic sites for Telfair Museums. Sammons oversees the reinterpretation of the museums’ two National Historic Landmark buildings, the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Owens-Thomas House. She also produces original exhibitions and related materials on decorative and fine arts and history. Her publications include exhibition catalogues The Story of Silver in Savannah: Creating and Collecting Since the 18th Century; “The Art of Kahlil Gibran,” in The Art of Kahlil Gibran; The Owens-Thomas House; and Daffin Park: The First One Hundred Years. Recent originally curated exhibitions include Sitting in Savannah: Telfair Chairs and Sofas; Journey to the Beloved Community: Story Quilts by Beth Mount, and Beyond Utility: Pottery Created by Enslaved Hands.

Image of Andrew Bryan courtesy of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Website: http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/love/love.html This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text.

Image of First African Baptist Church, Savannah (Chatham County, Georgia) via Wikimedia Commons