by Nathan Stone

They weren’t all the same. We know of at least one soldier who had a conscience. There were several, actually. Most were weighty figures, captains and colonels who refused to follow orders. Some of them quit or went into exile. Others died. But I’m talking about conscripts, the powerless boys who were in military service when the decision was made to interrupt the institutional process of the Chilean state on September 11, 1973. When the elected socialist government of Salvador Allende was overthrown by the US-backed Chilean military. When those boys were commanded to arrest, torture, and kill their own brothers and sisters.

Rodolfo González was one such conscript. He was proud that he had been chosen for the Air Force. He was just eighteen. After the coup, he was commissioned to serve at the DINA, Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional. That was General Pinochet’s secret police.

Rodolfo wasn’t an agent, but he did participate. He had guard duty. He delivered messages. He got coffee for the boss when the boss got tired of torturing someone.

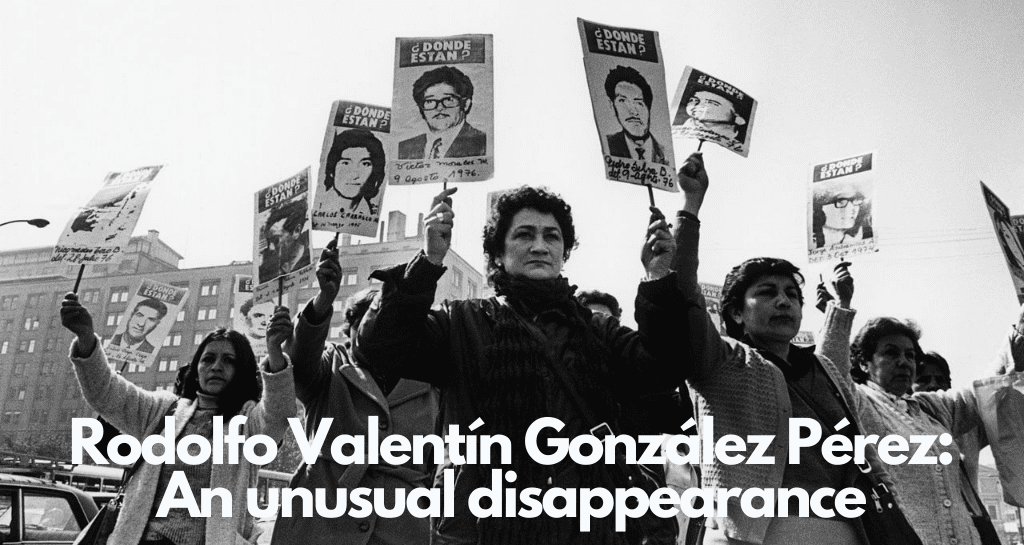

He lived with his aunt, María González. I knew her. She was a member of the Association of the Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared (Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos-Desaparecidos) until the day she died. She marched alongside Doris, Inelia, and the mothers of so many others who had disappeared, carrying her placard with the picture of Rodolfo. María González was an anomaly. Rodolfo was unusual company for the other prisoners at Villa Grimaldi, too.

María González said that, when her nephew started out at the DINA, he stopped wearing a uniform. They gave him a dark suit and black shoes. They picked him up in a car every day, a black Chevrolet Impala with tinted windows. Once, Rodolfo showed his military ID to his aunt. It identified him as a member of the DINA. That was a violation of protocol. The first one.

During the dictatorship, showing military ID was understood as a threat. It was a way to cut in line and get preferential treatment. But the DINA was different. You weren’t supposed to show that one anywhere, except at the door. They had several doors, actually, all of them, secret.

Rodolfo Valentín didn’t do well at the DINA. His own humanity betrayed him. Some days, he was sent to guard prisoners with bullet wounds, internal injuries, and broken bones at the Military Hospital. He would use his privileged access to tell to the prisoners what their respective situations were. Later, he contacted some family members, letting them know where their loved ones were and in what condition.

Maybe he wasn’t so clever. Maybe Rodolfo really thought that was how it was done. That was, after all, the Chilean way. But not in the DINA. One would think he had been thoroughly briefed. My suspicion is that our Rodolfo Valentín was very clever. If so, he was in open rebellion.

I don’t know if he really thought he had a chance of not getting caught. Maybe, like many others, he believed the military government would be over soon. Or, maybe, he was just very brave. Rodolfo was already a witness to the wildness of the DINA. If he wasn’t on board, then he was dangerous. The day would come when he would speak out.

He had an older brother who was a leftist militant. He had been given temporary asylum at the Argentine embassy.

Rodolfo was the third of ten. He had lived with his aunt since he was small. His father had died in ’64, leaving his mother more mouths than she could feed. His aunt had raised him to lighten the load. But someone had taught him very young that there are things one would never do to another human being. Perhaps that was his father.

He fell in step with the DINA at the beginning. Afraid, perhaps, or just following orders, as they say. And, maybe, he missed his father. That would leave any boy vulnerable to the military style. And maybe he was the favorite recruit of someone important. Military hierarchy works that way, believe it or not. And it just might be true that Rodolfo was momentarily tempted by the unlimited power of the DINA. It was naked, corrupt, clandestine, total power.

One thing we know for certain. His parents loved the cinema. That’s how he got the name Rodolfo Valentín. Perhaps, they were romantics, fans of Gardel, the tango singer. The cosmopolitan night life of Santiago in the ‘50’s ended, for them, abruptly. A heart attack, or an accident; I’m not sure. Rodolfo was ten when he went to live with his aunt.

The DINA caught him, of course. Communicating with the incomunicados. The next day, he was one of them. They took him from aunt’s home on the night of July 23, 1974. He could have met Inelia’s boy, Héctor, first as a DINA man, with infinite power over him, and, a few days later, as a comrade in the anonymous darkness at Villa Grimaldi.

During the Popular Unity years, Luz Arce had belonged to the Socialist Party. She was taken in June 1974. Rodolfo was her guard at the Military Hospital. He became too friendly. He even asked for her advice about how to get his brother out of the country.

Then, Luz Arce defected to the enemy. First, she became an informant and, later, a full-blown DINA agent. Stockholm Syndrome, that’s what they called it. When someone who is abducted begins to collaborate with their abductors. It’s what happened to Patty Hearst.

In 1990, when military rule was over, Luz Arce recanted. She told everything she knew to the Rettig Commission. She said she saw Rodolfo at Villa Grimaldi. He had his leg in a cast. Out of desperation, he had thrown himself from the tower. Maybe he thought he could escape, but no one ever escaped from the DINA.

They might have thrown him from the tower. The DINA agents were especially cruel with Rodolfo. For them, he was a traitor. Because of his brother, they figured he was a leftist infiltrator.

That wasn’t true. The other prisoners even said he was different. He had no political background. Leftist parties had training. Militants knew the drill. They knew what to expect when they were tortured. Rodolfo, they said, was “like a virgin.” An inexperienced, innocent boy.

Luz Arce said that the last time she saw Rodolfo alive, he was stripped naked and hanging from a beam at Villa Grimaldi. We don’t know if he was hanging by his hands, by his feet, or in some unimaginably painful stress position, barely breathing and wishing he could stop.

In 1977, two Air Force officials showed up at his aunt’s apartment in Santiago to confiscate Rodolfo’s military insignia. It seems they made a special effort to make sure that he never reappeared. Or maybe they did it just to be cruel. Why they waited so long was a mystery.

If all children had someone to teach them right from wrong; someone who would say that sometimes the authorities are evil; that power and goodness are not the same thing; then there would be no DINA, no CIA black ops, no My Lai massacres. There would be no cruelty, no abduction and no torture. I am surprised that there were so few like Rodolfo. Sometimes, in this world, there seem to be more cowards than heroes, more darkness than light. It doesn’t have to be that way.

There were nearly 2,000 who disappeared in Chile between 1974 and 1976. Most of them were convinced of an ideology. They had chosen to sacrifice their lives for the dream of a better world. But Rodolfo’s option was more primitive. He decided that he could not become a torturer, even if it meant he would be tortured. He chose solidarity, and it cost him everything he had.

For more on Chile’s disappeared ones, see www.memoriaviva.com.