Institute for Historical Studies, Wednesday May 5, 2021

The History Faculty New Book Series presents:

Imperial Science: Cable Telegraphy and Electrical Physics in the Victorian British Empire

(Cambridge University Press, 2021)

A book talk and discussion with

BRUCE J. HUNT

Associate Professor of History

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/huntbj

In the second half of the nineteenth century, British firms and engineers built, laid, and ran a vast global network of submarine telegraph cables. For the first time, cities around the world were put into almost instantaneous contact, with profound effects on commerce, international affairs, and the dissemination of news. Science, too, was strongly affected, as cable telegraphy exposed electrical researchers to important new phenomena while also providing a new and vastly larger market for their expertise. By examining the deep ties that linked the cable industry to work in electrical physics in the nineteenth century – culminating in James Clerk Maxwell’s formulation of his theory of the electromagnetic field – Bruce J. Hunt sheds new light both on the history of the Victorian British Empire and on the relationship between science and technology.’Lucid, brilliantly well-informed and replete with fresh insights, Imperial Science is destined to be an indispensable classic. Bruce J. Hunt gives us a rich account of how radical developments in cable telegraphy and the theory of electromagnetism were intertwined, with profound consequences for the everyday lives of millions of people all over the world.’

–Graham Farmelo, Churchill College, University of Cambridge

‘Well before the internet, information flowed through British submarine cable telegraphy. Bruce J. Hunt’s fascinating study explores how physicists and telegraph engineers managed competing methods and demands to create this first global communications system. These nerves of empire transformed international affairs, accelerated commerce, provided rapid access to news, and revolutionized physics.’

–Kathryn Olesko, Georgetown University

With impressive skill, Bruce J. Hunt brings together the commercial and engineering practices of Victorian telegraphy with the construction of the new physics of electromagnetic field theory. In so doing, he powerfully reinvigorates the history of nineteenth-century physics as a major academic arena grounded upon, but not determined by, imperial engineering and technology.’

–Crosbie Smith, University of Kent

Dr. Bruce Hunt is an Associate Professor in the Department of History, at the University of Texas at Austin, where he specializes in the history of science and technology. He is the author of The Maxwellians (Cornell University Press, 1991) and Pursuing Power and Light: Technology and Physics from James Watt to Albert Einstein (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011). Professor Hunt’s current work focuses on the relationship between technology and science in the 19th century, and particularly on the interaction between theory and practice in the Victorian telegraph industry. He also has strong interests in the history of nuclear weapons and of evolutionary theory. His teaching interests include the history of modern science, the history of technology, and modern British history. Read more about this work on his profile page, and personal website.

This discussion is part of the IHS History Faculty New Book Series.

Sponsored by: Institute for Historical Studies in the Department of History, and Center for European Studies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

NEP Author Spotlight – Ilan Palacios Avineri

The success of Not Even Past is made possible by a remarkable group of faculty and graduate student writers. Not Even Past Author Spotlights are designed to celebrate our most prolific authors by bringing together all of their published content across the site together on a single page. The focus is especially on work published by UT graduate students. In this article, we highlight the numerous contributions to the magazine made by Ilan Palacios Avineri.

Ilan Palacios Avineri is a doctoral student in the Department of History at UT Austin. His research broadly focuses on the militarization of daily life during the twentieth century in Central America. More specifically, his Master’s Report traces the relationship between Cold War-era security initiatives and the post-peace policing of urban centers in Guatemala. In the process, he explores the United States’ role in the implementation and continuation of state surveillance in Central America and interrogates fundamental assumptions that preface U.S. foreign policy in the isthmus. Before arriving at UT, Ilan received his Bachelor’s Degree in History from Willamette University where he graduated cum laude.

The legend of La Llorona is ubiquitous in Latin America. The tale typically centers on a woman who, upon learning of her husband’s infidelity, drowns their son and daughter in a moment of madness. She soon realizes what she has done and drowns herself in a river. Despite her contrition, she is unable to enter heaven and wails incessantly throughout the night. For this reason, she is known as La Llorona, the weeping woman.

In Jayro Bustamente’s 2019 film adaptation, La Llorona cries for her children once more. But rather than being killed by their own mother, the Guatemalan director foregrounds Enrique Monteverde (Julio Díaz), a former Guatemalan general during the nation’s civil war, as the perpetrator.

Read the full review here.

Standing in the outskirts of western Huehuetenango, Juan Gonzalez described to me the fields which surrounded his childhood home during the 1970s. “Our family used to raise a few cows in this area,” he said softly, “I used to tend to one named Membrio.” The bull’s hair was tan and tough on the outside, like the quinces people often eat growing up in Guatemala. He remembered being very happy those days. “I grew up without shoes,” he said, “same as all my siblings…but we had enough for basic things…and we cared for each other.” But everything began to change for Gonzalez when a 7.6-magnitude earthquake struck in 1976 and the Guatemalan military started setting up l tents in those precious fields. His story captures the profound turmoil wrought by the Guatemalan military during the civil war, a pattern of disruption that continues to drive outwards migration extending even into the present.

Read the full article here.

Medical professionals are often viewed as apolitical, but what happens when they come to challenge a government? On February 4th, 1976, a cataclysmic earthquake brought an embattled Guatemala to its knees. Amidst a raging civil war, the terremoto (earthquake) razed countless houses and killed roughly 21,000 people in just 39 seconds. Thousands more emerged from the rubble with serious injuries and over a million, disproportionately Mayas from rural regions, were left homeless.

As Kjell Laugerud García’s right-wing regime scrambled to rebuild critical infrastructure, the country’s crippled hospitals became inundated with a flood of patients. In the crisis’s aftermath, doctors and nurses grew increasingly embittered by the abysmal state of public hospitals and began to agitate for more rights.

Read the full article here.

Speaking in Honduras’ Río Blanco in 2013, Berta Cáceres rallied a sea of supporters against the construction of a new hydroelectric dam. She stressed that the joint economic effort, pursued by China’s state-owned Sinohydro company, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation, and Honduras’s Desarrollos Energéticos company, threatened to disrupt countless communities along the Gualcarque River. The project would not only prevent villagers from accessing water for agricultural and traditional medicines, but signaled the plundering of sacred lands. After lambasting the dam, Cáceres briefly paused to ask her supporters if they understood the risks involved in fighting the powerful interests before them. “Are you sure you want to fight this project,” she asked with intensity, “[because] I will fight alongside you until the end, but are you, the community, prepared?” The captivated crowd instantly raised their hands in support of Cáceres and the forthcoming fight against the imperialist venture. Just three years later, however, Cáceres was brutally murdered in her hometown of La Esperanza in western Honduras.

Read the full review here.

Sitting in a humble home in Huehuetenango, Manuel Alvarez told me the story of his near execution at the hands of the Guatemalan military. It was 1982 when the soldiers, under the direction of a Pentecostal dictator, first shoved his helpless body to the pavement and then placed an ice-cold muzzle against his back. “They told me that I better believe in Jesus,” he said softly, “because only Dios could save me from their bullets.” While Alvarez miraculously survived this encounter, he returned home that night deeply disturbed by the soldiers’ threats. He knew that his country’s military frequently killed, mutilated, and disappeared civilians. Yet he never before experienced how swiftly his body could be seized without repercussions or retribution. If he were to die on that pavement, he imagined, his family was unlikely to identify him and they would be forever haunted by not knowing what happened. In the wake of this terror, Alvarez called his brother Felipe to his bedroom and asked him to tattoo both his arms, to identify his body if need be.

Read the full article here.

From Peaceful Village to Army Outpost: Memories of Militarization in Huehuetenango

Standing in the outskirts of western Huehuetenango, Juan Gonzalez described to me the fields which surrounded his childhood home during the 1970s. “Our family used to raise a few cows in this area,” he said softly, “I used to tend to one named Membrio.” The bull’s hair was tan and tough on the outside, like the quinces people often eat growing up in Guatemala. He remembered being very happy those days. “I grew up without shoes,” he said, “same as all my siblings…but we had enough for basic things…and we cared for each other.” But everything began to change for Gonzalez when a 7.6-magnitude earthquake struck in 1976 and the Guatemalan military started setting up l tents in those precious fields. His story captures the profound turmoil wrought by the Guatemalan military during the civil war, a pattern of disruption that continues to drive outwards migration extending even into the present.

The soldiers began storming Huehuetenango in the aftermath of the 1976 terremoto(earthquake). The earthquake had leveled houses, roads, and bridges across the country, and the army needed to reconstruct critical infrastructure. Specifically, the military sought to build a new base in Huehuetenango, the Quinta Brigada de Infanteria MGS, as a staging ground for attacks against the insurgent Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP). The armed forces believed that this massive project could be achieved through the labor of hundreds of Huehueteco/as, who, in their view, would work for little money to build their damaged homes.

Gonzalez remembers being drawn into the Guatemalan military’s construction project in 1976. On his first day working on the base, he was tasked with trenching. He dug alongside indigenous Mayas who the army trucked in from neighboring villages to exploit for the most grueling tasks. Occasionally, the trenches would collapse, Gonzalez recalled, “and the ground would open and swallow people whole.” Twice a week, soldiers would arrive from Guatemala City in armored jeeps, carrying cases of cash to pay the laborers who earned roughly 30 cents for two weeks’ work.

Occasionally, the trenches would collapse, Gonzalez recalled, ‘and the ground would open and swallow people whole.‘

The army effectively transformed Huehuetenango’s western outskirts, the Gonzalez family’s neighborhood, into a full-blown military town. Despite the poor pay, “which was just barely enough for food,” hundreds flocked to the base to work as laborers, plumbers, masonry workers, and carpenters. They constructed sewer lines, guard towers, and prison cells. These workers did not know that such sites would later be used to torture suspected subversives.

For Gonzalez, who was 17 at the time, this period marked the end of his childhood. The Guatemalan Civil War had officially arrived in Huehuetenango. When construction on the base ended, the armed forces became a permanent feature in the town. Soldiers began infiltrating communities in the early 1980s, conscripting all the city’s men into patrols called the Patrullas de Autodefensa (PACs). These civil defense units were tasked with monitoring their own neighborhoods for suspicious activity. Troops would seize people off the streets near the town center or use comisionados (local military leaders) to ensure civilian participation. “None of us wanted to do it,” Gonzalez said, “but if you didn’t join, they could kill you for being a suspected guerrilla.”

On some days, even PAC membership did not offer protection from the Guatemalan Army’s suspicion. Gonzalez’s brother, Antonio, recalled being ambushed by soldiers one day. The army — looking for guerrillas suspected of bombing a nearby airfield —grabbed Antonio off the streets near his home. The soldiers beat him up and strangled him. He only survived by pretending to be dead. “They eventually stopped,” Antonio said softly, “they said, ‘just leave him, he’s dead already’.”

This violent episode was one among many that consumed the life of the Gonzalez family during this period. “They grabbed me off the street too once,” he said, “and attacked me after bursting into my friend’s house.” He began planning when he could he leave home and which roads to take to avoid being stopped and frisked by troops.

By the mid-1980s, the military’s surveillance pushed Gonzalez into a deep depression. “I saw so much destruction,” he shared, “I knew people who just vanished…there was no future for any of us.” He felt sick constantly, from headaches, nausea, and fatigue. “I used to save all my money to go to the doctor…” he remembered, “and they would tell me nothing was wrong with me.” But eventually, Gonzalez decided to flee to the United States. “As soon as I made that decision…I felt healthy again…and suddenly there was hope.”

Gonzalez’s story reveals the effects of the Guatemalan military’s counterinsurgency campaign on one small community in Huehuetenango. Over the course of a decade, the armed forces transformed a relatively peaceful town into a military outpost. They conscripted citizens into their campaign and terrorized communities in the process. For people like Gonzalez, the troops reduced life to a set of strategies for survival and eliminated the hope of a better future. In many ways, this story captures the physical and emotional costs of the Guatemalan military project writ large.

Perhaps, most importantly, Gonzalez’s description of the army’s relentless intimidation during the Cold War also resonates with what historians Julie Gibbings and Heather Vrana call “post-peace Guatemala.” After the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996, which formally ended the Guatemalan Civil War, the country’s security forces continued to monitor young men across urban centers. Police officers routinely cast them as gang members or, at the very least, gang sympathizers. Such social marginalization has become a principal factor driving Guatemalan youth into gangs. In this way, the testimony of Juan Gonzalez not only highlights Guatemala’s longer history of state terror, but implores us to consider the continued human costs of police and military surveillance.

Not Even Past, Year in Review, 2020-21

Year in Review 2020-21 by Adam Clulow

IHS Panel: Oil, Water, and Climate: Environmental Histories of Texas

Institute for Historical Studies, Monday April 12, 2021

Featured Panelists:

- “Arroyo Flood Control in the Chihuahuan Desert”

C. J. Alvarez

Assistant Professor, Department of Mexican American and Latino/a Studies

Faculty Affiliate, Department of History and Center for Mexican American Studies

University of Texas at Austin

Abstract: Deserts are, by definition, dry places. They are implicated in global climate change just as much as coastal regions, but instead of sea level rise and tropical storms, deserts are afflicted by widespread droughts well beyond the threshold of their natural aridness. In this talk, however, I will introduce you to an extremely local way of understanding water in the Chihuahuan desert, the largest desert in North America. Focusing on arroyo flood control projects, I aim to illuminate an important feature of desert people’s lives that is almost always overlooked or taken for

granted. This localized focus argues for a broader approach to the environmental history of deserts that focuses on desert dwellers instead of outsiders’ reactions or impressions of drylands.

- “Texas Climate Change: Past, Present, and Future”

Jay L. Banner

F. M. Bullard Professor of Geological Sciences, the Jackson School of Geosciences, and

Director, Environmental Science Institute.

University of Texas at Austin

Abstract: Texas’ climatological and geopolitical location has the potential to put extreme stress on its water and other resources. Paleoclimate records indicate that the region experienced periods of significant drought over the last thousand years. These droughts were longer than the 1950s ‘drought of record’ that is commonly used in planning and occurred independently of human-induced climate change. Model simulations for the 21st century project that Texas will experience droughts that are unprecedented in terms of length and intensity. A projected doubling of the state’s population by mid-century will drive increased demand for water, which will create synergistic challenges to the state’s resilience.

- “Deep Roots Make Strong Trees: Climate Adaptation Rooted in Community History”

Alison M. Meadow

Associate Research Professor, Arizona Institutes for Resilience

University of Arizona

Abstract: Communities throughout the Southwest are facing an uncertain future as climate change places our health, infrastructure, and natural environments at risk. This talk will focus on using community-based research approaches in order to ground climate change adaptation planning in the history and culture of communities so that long-term plans build on community strengths and priorities, even as we recognize the need for change to meet the challenge of our new climate reality.

- “The Petropolis: Where Oil and Water Meet”

Christopher C. Sellers

Professor of History, Stony Brook University, and

Research Fellow, Institute for Historical Studies, University of Texas at Austin

Abstract: If oil and water have a sturdy reputation for not mixing, Texas has long been a place where they unavoidably meet, especially in cities that arose on the back of the state’s oil industry, Petropolises. Taking the Houston metro area as an example, my talk will sketch out three eras from the late nineteenth century to the present in its historical relationship between water and oil. In the first two, while it also weathered occasional storms and floods, this like other cities associated with the petroleum and petrochemical industries increasingly took toxic pollution as its main waterborne challenge. More recently, the prevailing threat has come from hurricanes and floods, intensifying thanks to the global effects of its favored industry and placing the entire region in a new kind of jeopardy.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Review of Memory’s Turn: Reckoning with Dictatorship in Brazil by Rebecca J. Atencio (2014)

On November 18, 2011, Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff launched the National Truth Commission (Comissão Nacional da Verdade or, CNV). The CNV’s mandate included the investigation of torture, disappearances, executions, and other human rights abuses committed between 1946 and 1988. The commission’s period of inquiry covered twenty-one years of military rule, from 1964 to 1985.[1] The National Truth Commission began more than two decades after the dictatorship’s end, and this delay makes Brazil one of the last countries in Latin America to undertake a state-sponsored investigation of human rights violations committed during the Cold War.

Source: Isaac Amorim

Brazil, the third country in Latin America to undergo a democratic transition, has lagged behind many of its neighbors in the fight for truth and accountability. This occurred, in part, because of the gradual nature of the transfer of power. The military regime had achieved a relatively successful socioeconomic record and maintained a significant level of societal support. As a result, the armed forces exercised a high degree of control over democratization and successfully negotiated the conditions of this transition.[2]

Among the most substantial concessions won by the military was the 1979 Amnesty Law, which granted pardons for political or related crimes perpetrated between 1961 and 1979. Interpreted broadly since its passage, the 1979 amnesty has guaranteed impunity for state agents who committed human rights abuses. In Memory’s Turn: Reckoning with Dictatorship in Brazil, Rebecca J. Atencio, a professor of Brazilian literary and cultural studies, takes 1979 as democratization’s starting point and traces Brazil’s transitional justice process within a regional context.

The first book to analyze institutional and cultural responses in the aftermath of state terrorism in Brazil, Memory’s Turn (2014) seeks to understand the dynamic relationship between transitional justice mechanisms and exceptional cultural works (literature, television, film, and theater). Atencio’s innovative approach attempts to bridge two distinct fields: memory studies and transitional justice studies. Memory’s Turn asks readers to consider whether activity in one realm affects outcomes in the other. Atencio does not argue there is a causal relationship between artistic-cultural production and institutional mechanisms, but she does contend that interplay between the two realms can “magnify and prolong the impact of both and thereby lay the foundation for further institutional steps.”[3]

Atencio primarily concerns her study with the public reception and framing of cultural works. This emphasis leads her to rely on mass media, scholarly criticism, and published interviews by artistic producers (memoirists, actors, network producers, screenwriters) as well as the cultural works themselves. Although Atencio consulted scholars, creators, and activists during her research, she does not include personal interviews in her analysis. The reliance on published statements reflects her desire to understand how cultural producers framed their works and agendas in public debates.

In order to study the interaction between cultural production and transitional justice, Atencio first selected key institutional measures and then identified “linked” works. She considers cultural and institutional acts linked when they launch around the same time, and the general public begins to associate the two events with one another. This creates what Atencio defines as an “imaginary linkage.” Once the public has paired cultural and institutional mechanisms, individuals or groups can leverage the connection in order to promote their agenda. Atencio refers to this multi-part process as a “cycle of cultural memory.”[4]

Over four chapters, Memory’s Turn traces four cycles of cultural memory that took place between the 1970s and early 2010s. Not all works that emerge concurrently with an institutional mechanism become paired, so Atencio focuses her analysis on a few exemplary artistic-cultural productions that achieved this imaginary linkage. Chapter one analyzes how Brazil’s Amnesty Law became associated with two memoirs published by former militants: O que é isso, companheiro by Fernando Gabeira and Os carbonários by Alfredo Sirkis. The following chapter explores the television mini-series Anos rebeldes, partially inspired by Sirkis’s memoir. The show coincided with the impeachment process initiated against Fernando Collor de Mello, Brazil’s first-democratically elected president following the dictatorship, and became tied to popular student protests. In chapter three, she examines Fernando Bonassi’s novel Prova contrária in conjunction with the commission formed to award reparations to the families of those disappeared under the military regime. The final chapter investigates the connection between the play Lembrar é resistir and the establishment of Brazil’s first official site of memory at a former torture center in São Paulo.

By evaluating individual cycles of cultural memory, Memory’s Turn moves chronologically from the dictatorship’s end to the present day. Atencio brings these case studies together in her concluding chapter, which analyzes the longer arc of transitional justice and collective memory processes in Brazil within a global context. Ultimately, Atencio concludes that the linkage between cultural works and institutional mechanisms can foster wider public engagement and new efforts to reckon with the past.[5] As a result, cultural producers, along with human rights groups and activists, have led the turn to memory in Brazil and pressured the state to abandon its politics of silence.

Although Brazil’s long period of official silence presents some challenges to transitional justice studies, the Brazilian case emerges as a test case to assess the impact of delayed mechanisms. Unlike its regional counterparts, Brazil has adopted a more gradual approach to reckoning with its authoritarian past. The first institutional measure, a reparations program, did not arrive until ten years after the democratic transition. As trials and memory work continue to progress throughout Latin America, Brazil provides insight into how and why transitional justice approaches change over time. Shifting social and political landscapes influence trajectories and outcomes.

Memory’s Turn traces the evolution of Brazil’s transitional justice process and acknowledges its complexities without treating the Brazilian experience as unusual or exceptional. By placing Brazil within a regional context, Rebecca Atencio offers a unique theoretical insight for transitional justice studies. Memory’s Turn provides scholars a model for conceptualizing the dynamic relationship between legal mechanisms and cultural works in post-conflict societies. Over the long term, Atencio’s theoretical framework will apply to other national and regional contexts and help scholars better understand the long-term impact of transitional justice measures in post-conflict societies.

[1] “Brazilian Truth Commission Has Historic Responsibility,” International Center for Transitional Justice, last modified May 11, 2012, https://www.ictj.org/news/brazilian-truth-commission-has-historic-responsibility.

[2] Zoltan Barany, The Soldier and the Changing State: Building Democratic Armies in Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012), 128.

[3] Rebecca J. Atencio, Memory’s Turn: Reckoning with Dictatorship in Brazil, (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014), 8.

[4] Ibid, 6-8.

[5] Ibid, 125.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Confessions of an Archives Convert: Reflecting on the Genaro García Collection

From the editors: In 2021, Not Even Past launched a new collaboration with LLILAS Benson. Journey into the Archive: History from the Benson Latin American Collection celebrates the Benson’s centennial and highlights the center’s world-class holdings.

This article first appeared in Tex Libris, a blog from the Office of the Director of the University of Texas Libraries. The original can be accessed here.

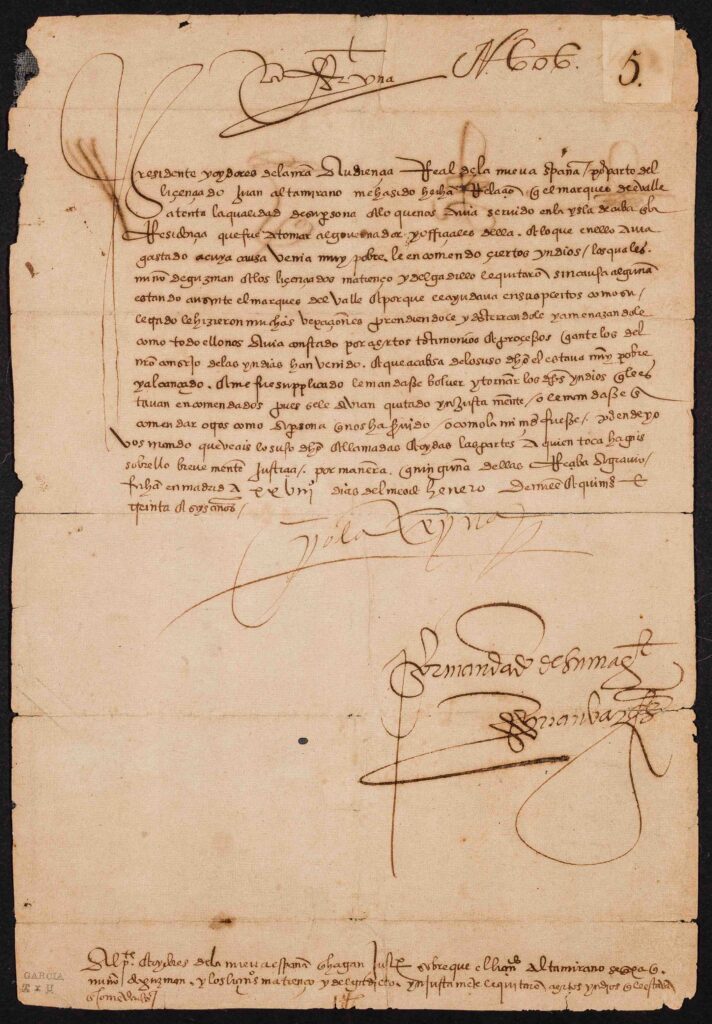

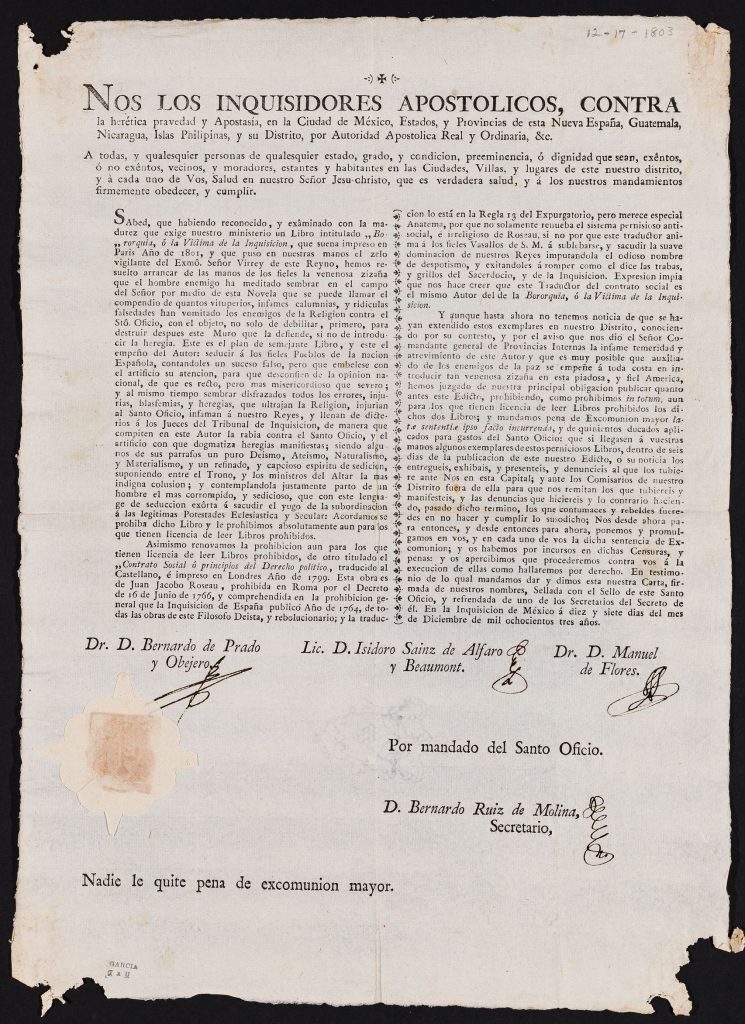

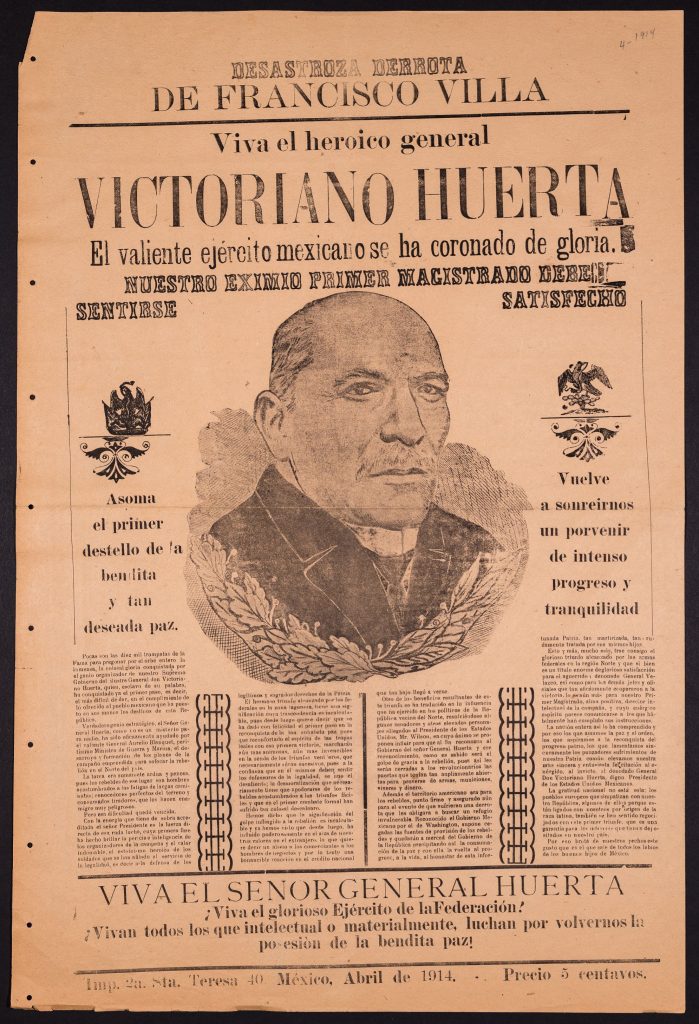

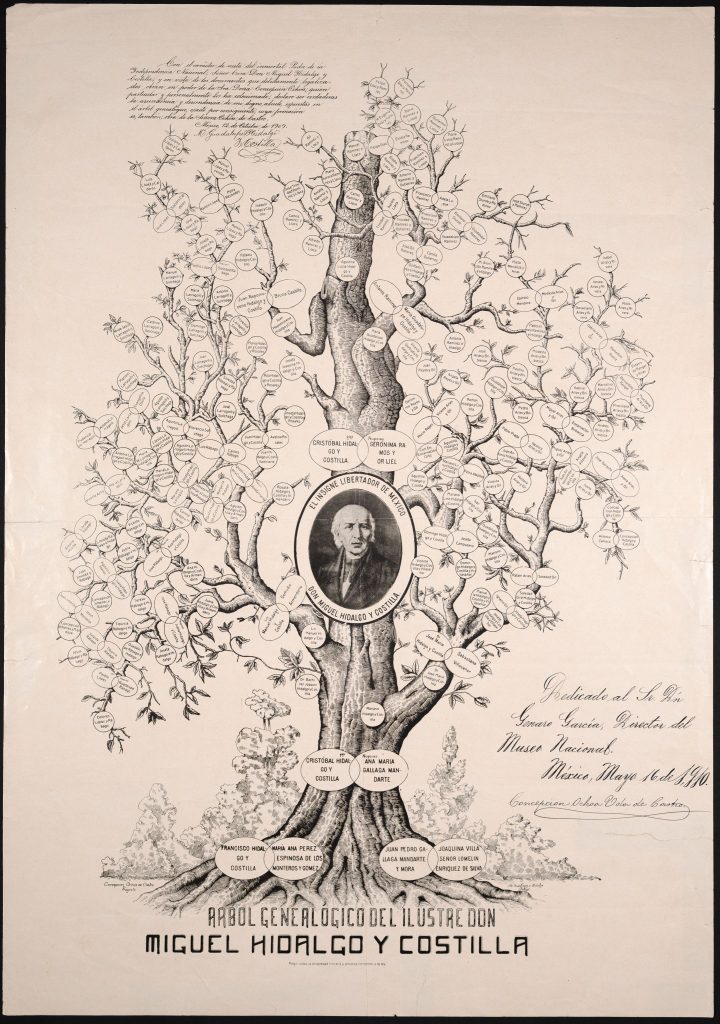

Voluminous lists of banned or redacted books, laced with sanctimonious commentary—or, early modern Spanish “cancel culture.” The illustrated family tree of a womanizing, bald curate named Miguel Hidalgo. Op-eds fawning over every viperous protagonist of the Revolution.

Researchers will find these items and more in the Genaro García Collection. A Zacatecan politico-cum-historian, and eventual director of Mexico’s Museo Nacional de Historia, Arqueología y Etnología, García began amassing books and other items documenting the history, culture, and politics of his country at a young age—a habit he, thankfully, never broke. In 1921, a year after his death, García’s family sold his vast treasure trove of Mexicana to the University of Texas after the Mexican government had reportedly demonstrated little interest. Seven tons of manuscripts, books, periodicals, photographs, and other printed materials made their way to Austin, becoming the seeds of what would flourish into the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection. It is one of the world’s premier archives for the Mexicophile.

Unlike many aspiring young historians, I was never a devotee of archives. I never revered the yellowed, brittle sheets of paper and the “stories” they harbored. Nothing was less appealing to me than spending the better part of a workday in some record office, wearily attempting to distill something relevant from a sea of irrelevancies, surrounded by researchers whose social ineptitude rivaled my own. I had ventured into multiple repositories and each time failed to become a convert. Perhaps this is why I gravitated toward intellectual history when it came time to find my niche. I am a believer in the book and the essay—heresy to the ears of some in the historical profession.

Then I began my position as the Castañeda Graduate Research Assistant at the Benson Latin American Collection. The job entailed creating metadata for digitized selections from the García Collection. I considered it a simple way to add some much-needed lines to my curriculum vitae, not to mention supplement my miserly graduate student salary. Yet it ended up washing away much of the aversion I felt toward archives, and introduced me to another career possibility.

After the initial new-job jitters, there was something serenely satisfying about delving into this collection. I was not a visiting researcher working against the clock to find useful bits of evidence for my own studies. I was there to calmly soak it all in, and then produce data, without any personal motive. Moreover, examining these raw materials of Mexican history proved to be a first-rate course in the subject—far more enlightening than any three-month-long seminar could ever be.

Writing metadata is, essentially, an element of the historian’s craft. One has to sit with and scrutinize an item in order to correctly interpret it. Often, this requires a healthy dose of research. Because I was not trained as a historian of colonial Latin America, documents created before the 19th century required additional research to properly contextualize them, as well as a resolute eye to decipher early-modern script. Then there is the authorial question, which occasionally demands another mini investigative journey. The end products are detailed, bilingual descriptions, and other data that, ideally, facilitate the researcher’s job.

I began working mostly with documents dating from about 1810 to 1920. The Images and Imprints section of the García archive consists of graphic materials, such as maps, lithographs, and posters. The Broadsides and Circulars portion, on the other hand, is more textual and consists of widely distributed papers relating to Mexico’s War of Independence (1810–1821) and the Revolution (1910–1920), but is no less captivating. These approximately 1,200 items are now viewable on the collections portal, and materials from the photographs, archives and manuscripts, and rare books parts of the collection are continually being uploaded.

Currently on my docket are digitized selections from Archives and Manuscripts. This section contains individual historical manuscripts from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Those from the 1500s have proven to be the most challenging, not only due to my lack of paleography skills but also my unfamiliarity with early-modern Spanish grammar. But a fair share of focus and tenacity goes a long way. The “Archives” portion holds the papers of several prominent 19th-century characters, such as Lucas Alamán, the conservative statesman and intellectual, and Antonio López de Santa Anna, the peg-legged vendor of national territory. It will be a welcome break from my travails through the colonial era.

I am glad to play a pivotal role in the Benson’s initiatives to develop its digital collections. Digitization, after all, serves to democratize research and pedagogy by making rare and remote materials easily accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Now, scholars unable to jet off to Austin from, say, Genaro García’s home country of Mexico, can consult his collection from their laptops. Digital content also allows for innovative exhibition practices, like online showcases with interactive features. And perhaps most importantly, digitization safeguards our cultural heritage by producing a virtual “backup.”

The digitization and metadata creation for the Images and Imprints and Broadsides and Circulars materials were generously funded by the Latin Americanist Research Resources Project (LARRP), Center for Research Libraries, with additional funds provided in honor of Consuelo Castañeda Artaza and her sons. Of course, none of this could have been accomplished without the dedication of several Benson employees. David Bliss, Itza Carbajal, Robert Esparza, Mirko Hanke, Dylan Joy, Ryan Lynch, Madeleine Olson, and Theresa Polk all made indispensable contributions to the digitization and publication of these items.

It has been over two years since I began this position. I am still a devout fan of books and other easily available, published sources. But I am no longer agnostic about the pleasures of archives, at least not the one described here.

Diego A. Godoy is a PhD candidate in Latin American history at The University of Texas at Austin and Castañeda Graduate Research Assistant at the Benson Latin American Collection. Before coming to Texas, he earned an MA in history from Claremont Graduate University. He is broadly interested in the intellectual and cultural history of the region. His particular focus is on the history of criminology, detection, and crime writing. He is author, most recently, of the article “Inside the Agrasánchez Collection of Mexican Cinema,” which appeared in the fall 2020 issue of Portal magazine.

Support the Benson Centennial! Visit benson100.org to learn more.

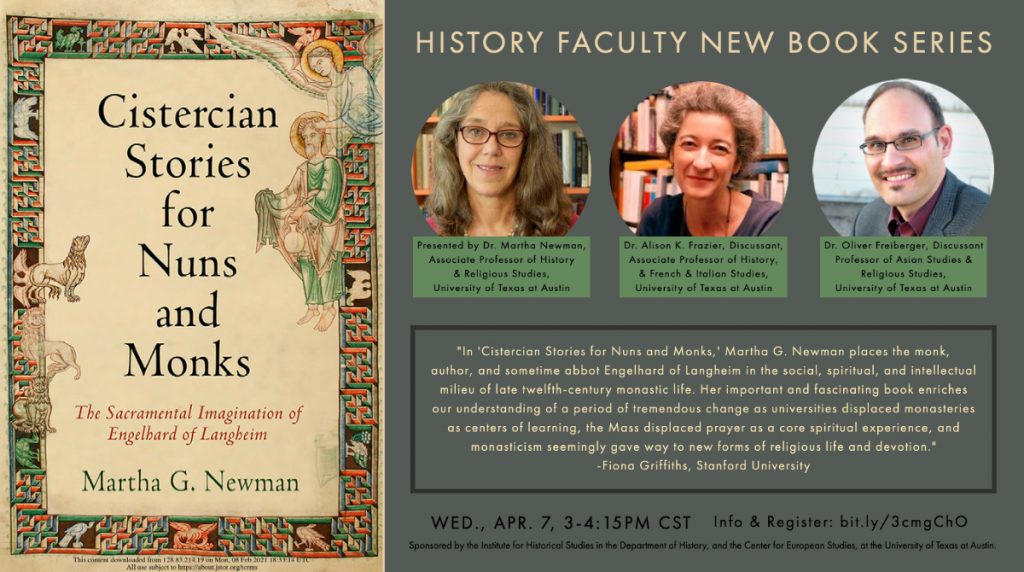

IHS Book Talk: Cistercian Stories for Nuns and Monks

Institute for Historical Studies, Wednesday April 7, 2021

The History Faculty New Book Series presents:

Cistercian Stories for Nuns and Monks The Sacramental Imagination of Engelhard of Langheim

(University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020)

A book talk and discussion with

DR. MARTHA G. NEWMAN

Associate Professor of History

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/newmanmg

With discussants:

DR. ALISON K. FRAZIER

Associate Professor of History

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/history/faculty/akf7035

DR. OLIVER FREIBERGER

Professor of Asian Studies and Religious Studies

The University of Texas at Austin

https://liberalarts.utexas.edu/asianstudies/faculty/of63

Around the year 1200, the Cistercian Engelhard of Langheim dedicated a collection of monastic stories to a community of religious women. Martha G. Newman explores how this largely unedited collection of tales about Cistercian monks illuminates the religiosity of Cistercian nuns. As did other Cistercian storytellers, Engelhard recorded the miracles and visions of the order’s illustrious figures, but he wrote from Franconia, in modern Germany, rather than the Cistercian heartland. His extant texts reflect his interactions with non-Cistercian monasteries and with Langheim’s patrons rather than celebrating Bernard of Clairvaux. Engelhard was conservative, interested in maintaining traditional Cistercian patterns of thought. Nonetheless, by offering to women a collection of narratives that explore the oral qualities of texts, the nature of sight, and the efficacy of sacraments, Engelhard articulated a distinctive response to the social and intellectual changes of his period.

In analyzing Engelhard’s stories, Newman uncovers an understudied monastic culture that resisted the growing emphasis on the priestly administration of the sacraments and the hardening of gender distinctions. Engelhard assumed that monks and nuns shared similar interests and concerns, and he addressed his audiences as if they occupied a space neither fully sacerdotal nor completely lay, neither scholastic nor unlearned, and neither solely male nor only female. His exemplary narratives depict the sacramental value of everyday objects and behaviors whose efficacy relied more on individual spiritual formation than on sacerdotal action. By encouraging nuns and monks to imagine connections between heaven and earth, Engelhard taught faith as a learned disposition. Newman’s study demonstrates that scholastic questions about signs, sacraments, and sight emerged in a narrative form within late twelfth-century monastic communities.

- “In Cistercian Stories for Nuns and Monks, Martha G. Newman places the monk, author, and sometime abbot Engelhard of Langheim in the social, spiritual, and intellectual milieu of late twelfth-century monastic life. Her important and fascinating book enriches our understanding of a period of tremendous change as universities displaced monasteries as centers of learning, the Mass displaced prayer as a core spiritual experience, and monasticism seemingly gave way to new forms of religious life and devotion.”

–Fiona Griffiths, Stanford University

Dr. Newman is a scholar of medieval European history who explores the ways religious practices and ideas intersect with social change. Her research focuses on Christian monasticism, especially monastic miracle collections, monastic attitudes toward women and the poor, and religious conceptions of labor. In the last year, she has published two essays in addition to her book under discussion today. One, “Defining Blasphemy in Medieval Europe: Christian Theology, Law, and Practice ” appeared in Blasphemies Compared: Transgressive Speech in a Globalised World, edited by Anne Stensvold; and the other, “The Benedictine Rule and the Narrow Path: The Place of the Charter of Charity in the Exordium Magnum and Other Late Twelfth-Century Cistercian Texts,” appeared in La Charte de Charité 1119-2019. Un document pour préserver l’unité entre les communautés [The Charter of Charity 1119-2019. A document to preserve unity between communities], edited by Éric Delaissé. Her other publications include The Boundaries of Charity: Cistercian Culture and Ecclesiastical Reform, 1098-1180, and numerous book chapters and articles dealing with medieval Christianity. In 2006-07, she was the William Cottrell Member of the School of Historical Studies at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Princeton. Her work has been supported as well by the National Endowment for the Humanities and by competitive fellowships from the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Newman has served in numerous service positions during her tenure at UT-Austin, including Associate Chair of the History Department, Associate Director of the Plan II Honors Program, and Director of the History Honors Program. She is currently the Graduate Advisor for the Department of Religious Studies and the Director of the Medieval Studies Program. Her classes include “The Medieval Millennium,” “The Twelfth-Century Renaissance,” “The Crusades,” and “Religions in Practice.”

This discussion is part of the IHS History Faculty New Book Series.

Sponsored by: Institute for Historical Studies in the Department of History, Center for European Studies

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

This is Democracy – Afghanistan War

Guest: Dr. Aaron O’Connell is an Associate Professor of History at UT Austin and Director of Research at the Clements Center for National Security. He is a military historian who focuses on military strategy and culture. His first book was entitled, Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps. His second book was a collection of essays entitled Our Latest Longest War: Losing Hearts & Minds in Afghanistan. Dr. O’Connell served for 26 years in the U.S. Marine Corps, with the current rank of colonel. He served as a Special Advisor to General David Petraeus in Afghanistan. Later, he served as a Special Advisor to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, where he wrote on issues of terrorism and strategy. Dr. O’Connell also served in the Obama Administration as Director of Defense Policy & Strategy on the National Security Council Staff.

Jeremi and Zachary along with their guest, Aaron O’Connell discuss America’s longest war, the Afghanistan War, and the implications within our proposed withdrawal on the 20th anniversary of the September 11th attacks. Zachary sets the scene with his poem titled “When a War Lasts 20 Years”.

About This is Democracy

The future of democracy is uncertain, but we are committed to its urgent renewal today. This podcast will draw on historical knowledge to inspire a contemporary democratic renaissance. The past offers hope for the present and the future, if only we can escape the negativity of our current moment — and each show will offer a serious way to do that! This podcast will bring together thoughtful voices from different generations to help make sense of current challenges and propose positive steps forward. Our goal is to advance democratic change, one show at a time. Dr. Jeremi Suri, a renowned scholar of democracy, will host the podcast and moderate discussions.

This is Democracy – Black Resistance to Slavery in Early America and its Legacies

Guest: Daina Ramey Berry is the Oliver H. Radkey Regents Professor of History and Chairperson of the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin. She is a Fellow of the Walter Prescott Webb Chair in History and the George W. Littlefield Professorship in American History, and the former Associate Dean of The Graduate School. Professor Berry is a scholar of the enslaved and a specialist on gender and slavery as well as Black women’s history in the United States. Professor Berry’s books include: Swing the Sickle for the Harvest is Ripe: Gender and Slavery in Antebellum Georgia; The Price for Their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved from Womb to Grave in the Building of a Nation; and A Black Women’s History of the United States, with co-author Kali Nicole Gross.

Jeremi and Zachary turn to expert Dr. Daina Ramey Berry to discuss the history and legacy of slave revolts and maroon societies in the United States, and lack of education on these subjects today.

Zachary sets the scene with his poem, “One You Have Not Heard”.

About This is Democracy

The future of democracy is uncertain, but we are committed to its urgent renewal today. This podcast will draw on historical knowledge to inspire a contemporary democratic renaissance. The past offers hope for the present and the future, if only we can escape the negativity of our current moment — and each show will offer a serious way to do that! This podcast will bring together thoughtful voices from different generations to help make sense of current challenges and propose positive steps forward. Our goal is to advance democratic change, one show at a time. Dr. Jeremi Suri, a renowned scholar of democracy, will host the podcast and moderate discussions.