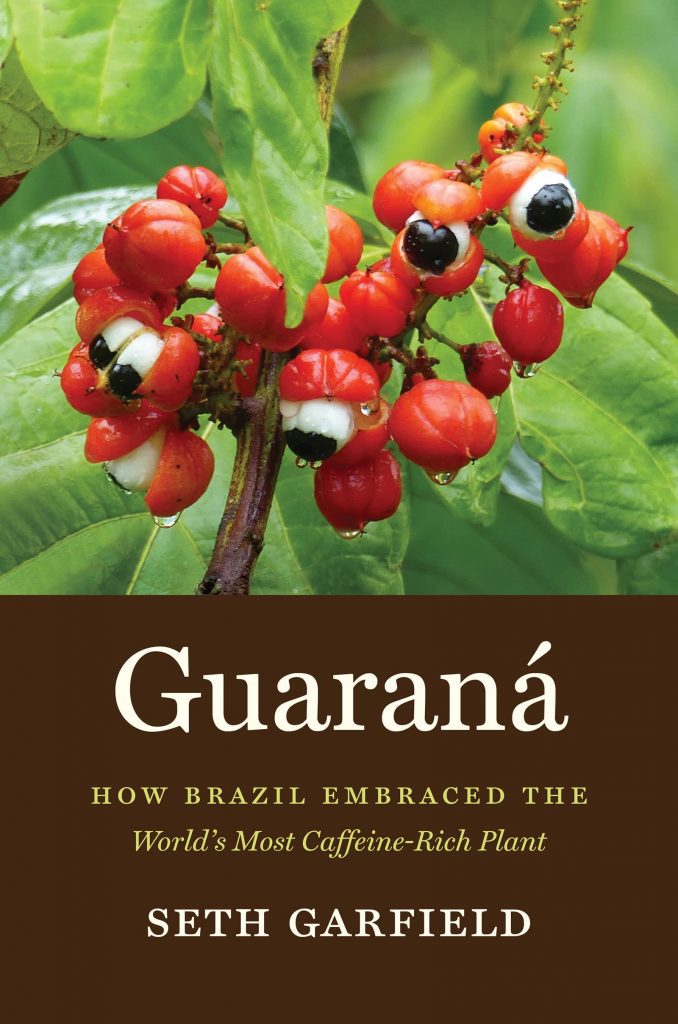

Guaraná: How Brazil Embraced the World’s Most Caffeine-Rich Plant is a luminous social biography of a single Amazonia fruit. Historian Seth Garfield re-invigorates the abiding relevance of the history of commodities as an entry point into Latin American history. As a history of consumption, science, and national mythology, the book invites readers into new terrain in the social life of things. Garfield explores guaraná’s many meanings and pathways over three centuries as it was transformed through Indigenous knowledge, European colonization, modern state-building, and the story of capital. By the mid-twentieth century, guaraná had become Brazil’s iconic national soda, famous for its golden hue and energetic punch. Garfield traces the many transnational dynamics and flows that shape guaraná’s uses and meanings. But the book as a whole keeps Brazil and Brazilians center stage.

Guaraná is a gem of a read, as exuberant as Guaraná Espumante champagne. Elegantly written and immensely interdisciplinary, Garfield seamlessly weaves anthropology, history of science, food systems analysis, feminist scholarship, cultural theory, and ethnic studies together. His narrative is peppered with ironic and often humorous insights alongside somber accounts of exploitation and loss. Who knew that guaraná had so many uses? At different times and places, it appears as a cosmic history of the gods, a sexual stimulant, a smart pill for children, a cure for “lady headaches,” and an on-ramp for women to enter public spaces. Lizzie Borden was high on guaraná tea when she allegedly axed her parents in the 1890s. Brazilian soccer teams relied on guaraná soda to fuel victories over Argentina in the 1950s. By the 1990s, Guaraná diet supplements promised lean and toned bodies ready for the beach.

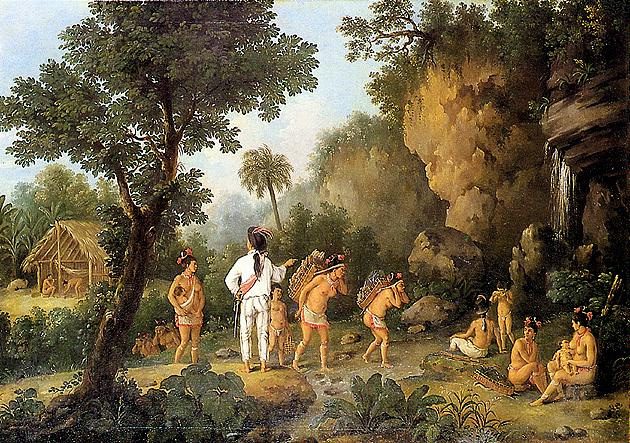

A singular achievement of this book is the way in which Garfield centers Indigenous knowledge and practice in the history of food and consumption. Very few histories of commodities do this, and I know of no book that does it so well. The monograph opens and closes with chapters on the Sateré-Mawé. The particularly insightful first chapter provides a rich discussion of Native production and use, sexual divisions of labor, Indigenous discovery, experimentation, and innovation. The author elaborates both an ethnography and an intellectual history of Sateré-Mawé meanings that makes a strong case for Indigenous knowledge as science. Garfield attributes the same explanatory power to Sateré-Mawé exploration and story-telling of guaraná as he does to eighteenth-century Jesuit plant collectors and nineteenth-century botanists who interpellated tropical plants within Western networks of knowledge.

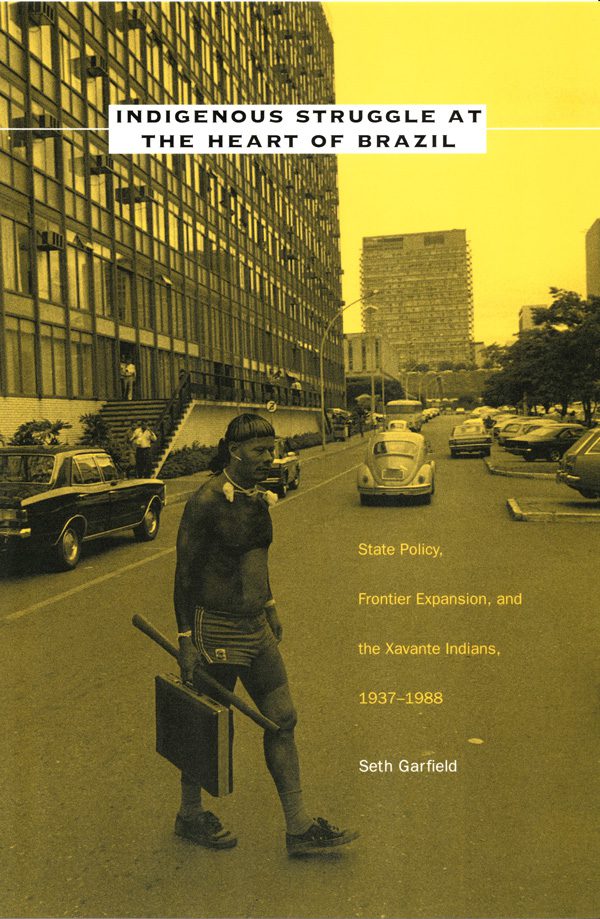

Other chapters argue that Indigenous knowledge formed a basis of modern medical and pharmaceutical development, even as Brazilian and American scientists elaborated racial hierarchies that occluded that truth. Garfield insists that modern-day scholars recognize Indigenous people as “colleagues” not mere “informants” of Western biochemistry and foodways.” He underscores that Indigenous people should be afforded similar intellectual property rights and centrality in the history of science. These arguments come to the fore in the book’s last chapter on “Indigenous Modernity,” where Garfield circles back to the insights of his own first monograph, Indigenous Struggle at the Heart of Brazil: State Policy, Frontier Expansion, and the Xavante Indians, 1937-1988 (2001). In Guaraná, Garfield highlights how Sateré-Mawé are politically savvy and modern in their own ways, despite the horrific violence and material loss that Indigenous people of the Amazon suffered during military rule. By the late twentieth century, the Sateré-Mawé were tapping into global discourses about Native sovereignty and Indigenous environmentalism to assert land rights and to forge a commercial presence in marketing their own guaraná as eco-friendly Fair Trade products for the Global North.

A second major contribution of Guaraná is the way it reverses the gaze of more conventional histories of commodities and consumption. Garfield asserts the importance of a plant and commercialized food product that never became a global hit. Despite the best efforts of advertisers and scientists, guaraná never had as much of a market outside Brazil. Histories of Latin American coffee, sugar, and other fruits like bananas and grapes, stake their importance on the fact that U. S.-Americans and Europeans consume these goods. Garfield shows that the commodity-subject need not circulate in the North Atlantic to be significant, even foundational, to Latin American histories. In this story, it is Brazilian actions and their impacts that matter most. Guaraná was transformed by international dynamics of colonialism and capitalism, science and technology, but why guaraná matters is a Brazilian story. The ‘transnational turn’ has produced many fine histories of how goods, people, and ideas circulate. Yet Garfield’s global framework emphasizes the effects of Brazilian agency and knowledge on Outsider Others: German Jesuits, Harvard scientists, U.S. corporations. He highlights Brazilian innovation in pharmacology and beverage manufacturing. All of this de-centers Europe and the United States within the history of commodities. If Brazil’s popular Brahma-brand guaraná soda built on German technologies for producing carbonated water or borrowed Coca-Cola’s marketing strategies, it was fundamentally a Brazilian invention, the taste for which did not originate in, or appeal to, the U. S. A.

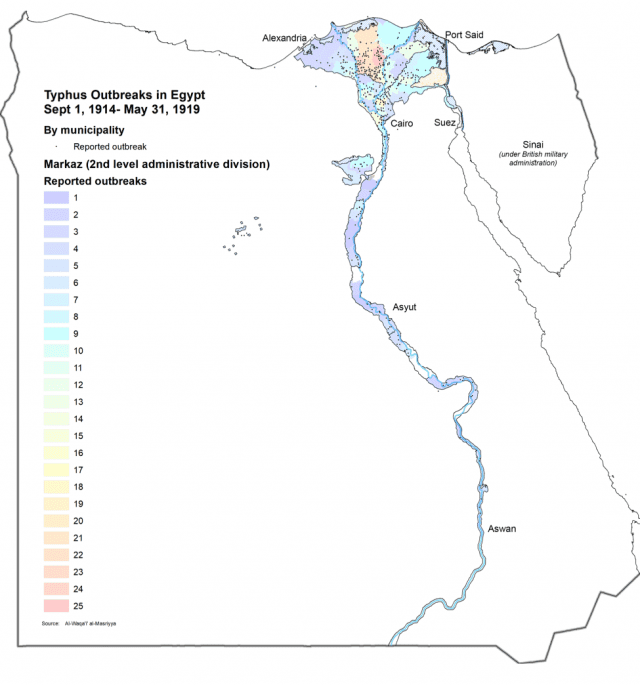

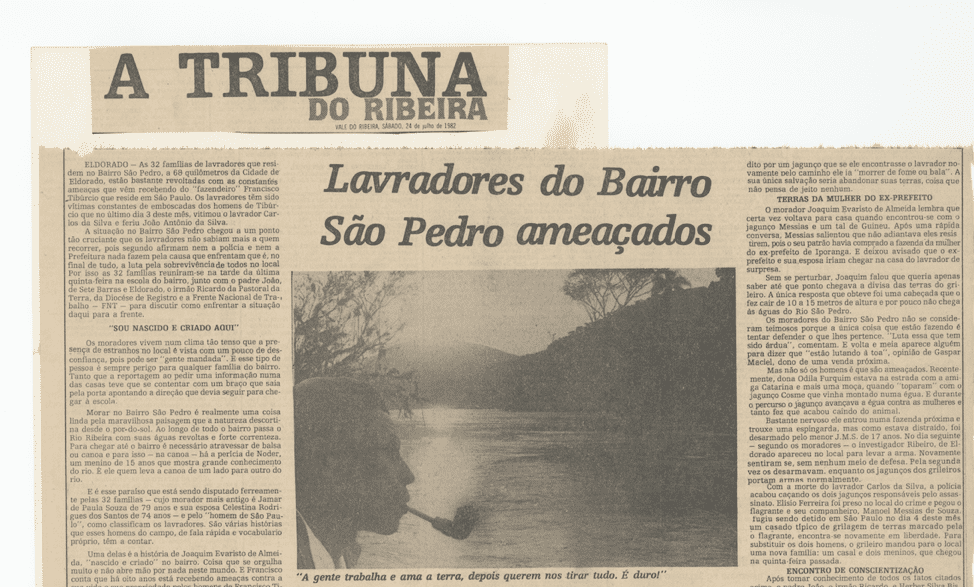

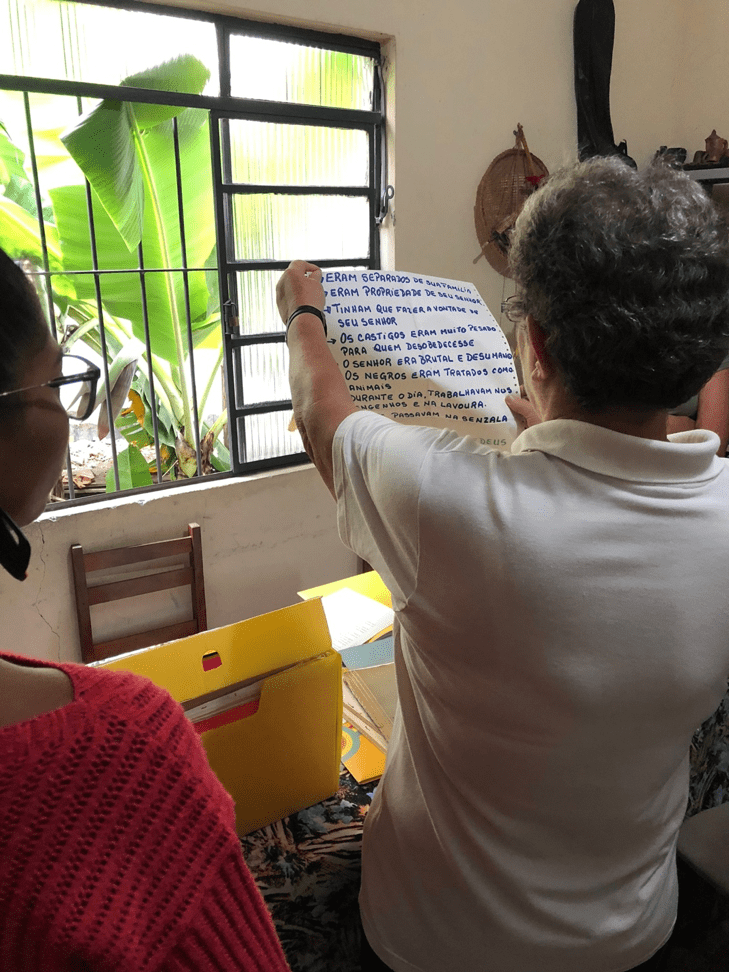

A third contribution is Guaraná’s emphasis on the history of meaning. As a historian of labor and commodities myself, I appreciated that Garfield places his main analysis of agrarian capitalism late in the book in chapter seven, which details guaraná’s economic boom during the military regime’s destructive “green revolution” in the Amazon. This important chapter underscores just how much the “economic miracles” of neoliberalism depended on authoritarian states that sought to conquer “final frontiers” of Indigenous and peasant lands. Historians of Chile, Peru, Colombia and elsewhere will recognize the pattern. But Garfield’s placement of this more familiar history of capitalist production near the book’s end stems from more than just historical chronology. Guaraná is imbricated in other forms of capitalist production long before the Cold War boom-years.

The late staging of political-economy in this history foregrounds knowledge-production and the history of cultural meanings as necessary antecedents to capitalist development. In this story of capital, guaraná had to first be imagined as desirable in the minds of scientists and doctors, Brazilian industrialists, a state longing for national symbols, women and men out on the town. This inverts the logic of most other histories of commodities that more often begin with what and how capitalism is producing, and then backs into a discussion of the social use and cultural meaning. As the logic goes, capitalists produce stuff to make money, and then figure out how to sell it; economic base begets the superstructure of cultural systems. Garfield flips that script and foregrounds the history of ideas and aspiration.

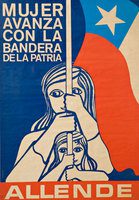

Finally, Garfield’s attention to how guaraná produces hierarchies of gender, race, and region deserves special praise. His analysis ranges from guaraná’s original “discovery” by a Sateré-Mawé woman and the strict sexual divisions of labor in which Native men cultivate the fruit and women prepare it as food, to later associations of guaraná champagne and dietary supplements with whiteness and urban cosmopolitanism, to guaraná’s modernization of patriarchy. Garfield chronicles how guaraná soda allowed women to sip non-alcoholic beverages in public, while men continued to have license to get soused on beer. Black bodies were associated with serving guarana to others, or, for Black men, to signify prowess in sports and music. Exotic spice for a more fundamentally white color of modernity. Garfield reminds us that “mass consumption” can both empower and subordinate. It is a terrain of struggle and constant transformation.

Heidi Tinsman, University of California, Irvine

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.