What happens when someone googles your name? Whether the search result pulls up your forgotten MySpace page highlighting your 2007 obsession with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows or your meticulously curated personal website, the answer to that question is entirely dependent on how you have cultivated your online presence. As we move further into the Digital Age, it is increasingly important as graduate students and scholars to establish ourselves online. The Internet is an invaluable resource to research, communicate, and share knowledge with a truly global community. Developing a strong online presence to take advantage of this unparalleled connectivity is a vital step to take in a young scholar’s career. In this article, I trace my journey to establish an academic presence online. I lay out three steps that I believe every young scholar can, and should, take to firmly establish an active and robust digital presence.

1) Department Profile

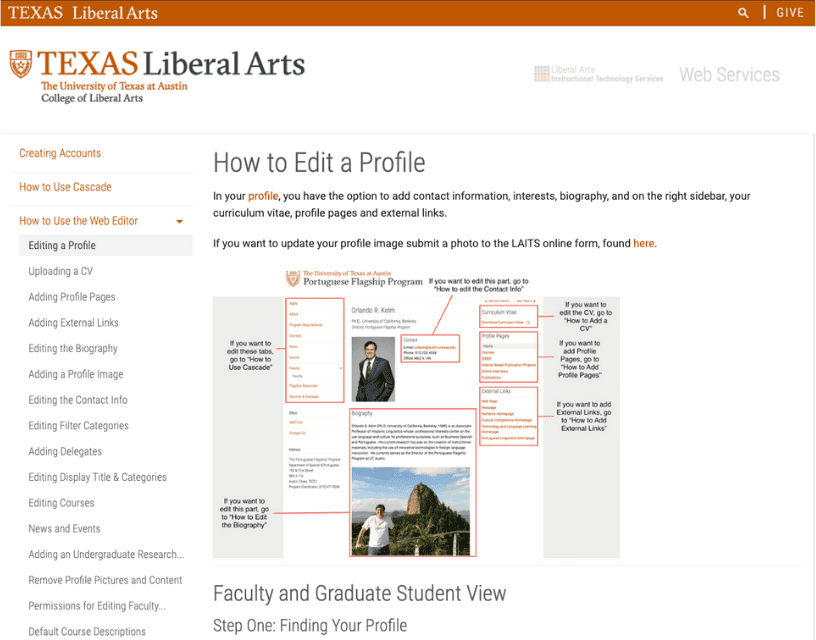

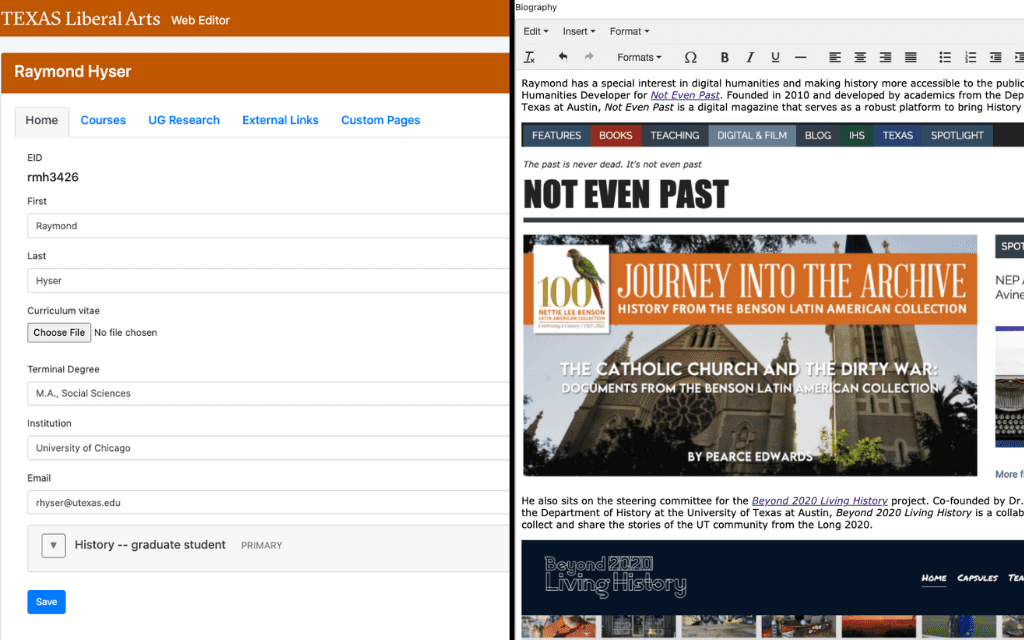

The first step to building your academic presence online starts on your department’s website with your student profile page. While I specifically discuss developing a UT student profile, the general process and the principles I touch on can readily be applied to a profile at any department and university. As a UT graduate student, a student profile page is automatically created for you. It is up to you, however, to develop it to its full potential. There are two key resources to use to create an outstanding UT student profile: the Web Editor and its companion website, the aptly named How to Use the Web Editor. Other universities will most likely have their own equivalents to these two sites. The “how-to” guide provides a wealth of information on the various aspects of the web editor and does a relatively good job walking you through the necessary steps to accomplish virtually everything you want to do with your profile. UT’s web editor provides a multitude of different fields for you to provide the information pertinent to building a successful student profile. The web editor is, unfortunately, a bit clunky and there is no “preview page” option for you to look at your changes before publishing, so plan accordingly!

There are several key elements that every profile should have. The very first thing you should add is an email address that you frequently check. No matter how good your profile is, if potential collaborators or employers cannot contact you, it’s not especially helpful. The second element to add is a short, but informative biography. Successful biographies take the form of the time-honored “elevator pitch,” but consider this your chance to deliver the most polished elevator pitch that you have ever given, albeit in written form. Think of the biography as a means to both advertise yourself and to stake out your scholarly territory within your particular field. The first one or two lines of your biography are critical as those are the lines that appear as part of the website preview in a Google search result. Do not write a novel for your biography as page viewers will be less likely to read a wall of text. Instead, aim for a few short paragraphs that highlight the most important details about your scholarly endeavors. The last critical component of your student profile is listing your scholarly fields or what the UT web editor classifies as “interests.” This section may seem superfluous, but it is an important one as it quickly conveys to your page viewers what kind of research you conduct and what topics interest you. Additionally, using terminology that is frequently used in your research field(s) increases the chances of other scholars encountering your profile through keyword searches in Google.

Additionally, there are several other sections that you can add to develop a truly successful profile. The first is images. Adding a high-resolution profile picture is a great addition to your page as it allows viewers to visually connect with you by putting a face to your name. Plus, it adds a bit more of your personality to your profile. Although you have to submit your intended profile picture through the LAITS online photo submission form to add it to your profile, the form is easy to fill out and is certainly worth it. Additionally, incorporating other visual material into your biography will create a more aesthetically pleasing profile and give you an additional opportunity to show off your work. This is especially true for UT student profiles as the default color palette is an overwhelmingly white page with some burnt orange accents, so adding colorful images from your work will elevate your profile and make it stand out. For instance, on my profile, I added screenshots of websites that I have worked on to break up the wall of text of my biography and to visually highlight projects that I am proud of. UT’s web editor also allows you to create custom pages that show up as hyperlinks along the right-hand side of your profile’s main page. Although the customization options are fairly limited, you can use them in a variety of different ways to highlight specific aspects of your work. The page that I customized houses all of my writings that I have written for Not Even Past under one roof. Adding a downloadable CV, as well as external links to your other projects and writings, are also great additions to your department profile. One of those external links could (and should) be a link to your academia.edu page, the next step to building your academic presence online.

2) Academia.edu Profile

Academia.edu is an academic research-sharing platform that allows academics, professionals, and students to upload and read scholarly work. The site has, at least at the time of writing this article, 156,949,639 registered academics and researchers, and hosts over 22 million uploaded papers. Needless to say, academia.edu boasts a massive scholarly ecosystem. Many people categorize academia.edu as an academic version of LinkedIn. While both websites share several key attributes, they ultimately serve different purposes and offer different services.

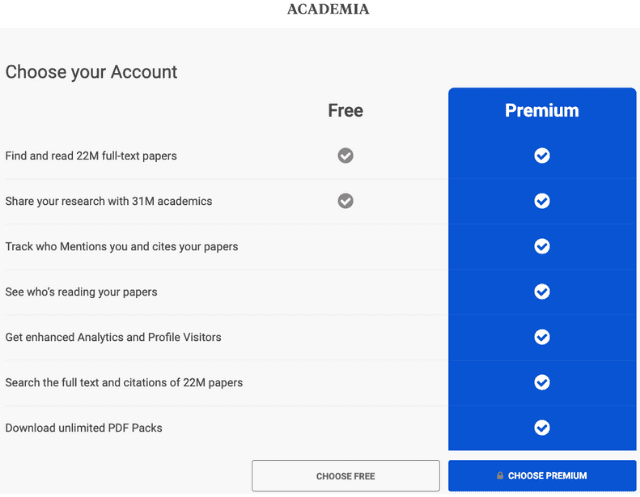

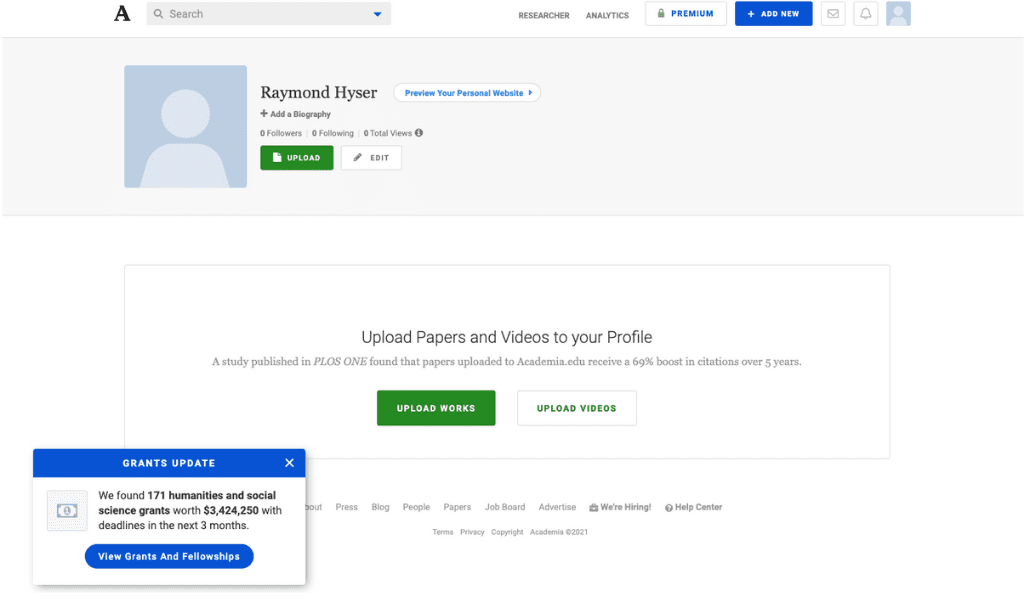

You can sign up for an academia.edu account using either a Google or Facebook account, or you can use an email address. I suggest signing up with a university-affiliated email or Google account to keep all your university-related correspondence and accounts in one place. Once you are signed up, you have the option of opening either a free or premium account. The free account gives you reading access to all the uploaded papers on the platform and allows you to upload your research as well. The free version also comes with a minimalist profile where you can write a biography, add your research interests, and arrange your uploaded papers. The premium account provides you with several added benefits, including tracking who mentions you and who cites your papers. You can also download unlimited PDF packs from the platform and see who is reading your papers. Academia.edu also recently added course offerings for premium account holders that provide resources on a variety of useful topics, such as grant writing. While the premium account is reasonably priced for graduate students, $49.50 billed annually, and offers some good features, I do not think the additional features justify the costs for most graduate students. That being said, later-stage graduate students with more publishable writings to upload may find the enhanced analytics of the premium account worth the cost. I went with the free account.

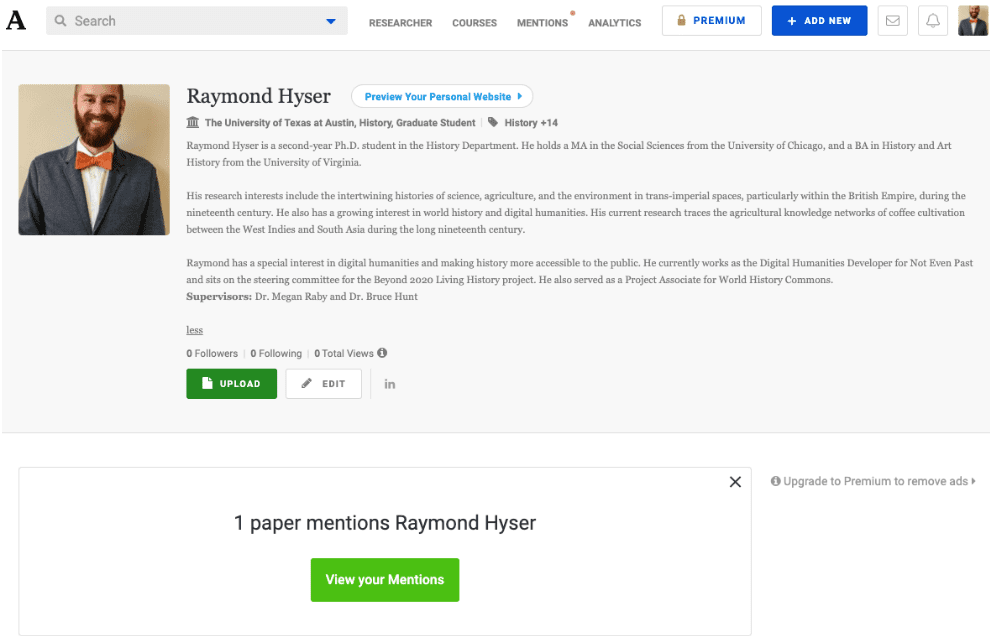

Once you have selected your account type, the next steps are to build out your academia.edu profile. Your academia.edu page should have the same three components as your departmental profile. Editing your profile on academic.edu is significantly easier than using UT’s web editor. Simply click on the “edit” button on your page and select which section you want to edit. Although it is easier to use than the web editor, you have fewer options on how to format your content and what elements you can incorporate into your profile. For instance, you cannot add images to your academia.edu biography like you can on your student profile. Adding a profile picture (which is recommended) can be tricky because you cannot edit photos within academia.edu and the website automatically centers the photo for you, which can lead to some unfortunate cropping mishaps. Since the website offers limited customization of your biography, I recommend writing only a short biography that provides pertinent biographical information and touches on the major aspects of your research. There is also a dedicated space within the biography tab to add the name(s) of your dissertation supervisor(s). Providing this information can be helpful and can potentially attract more traffic to your page. Like your student profile, adding your research interests helps page viewers to quickly identify the kinds of scholarly conversations you are interested in. These tags also have the added benefit of helping academia.edu’s algorithm create better reading suggestions for you. Your academia.edu profile also provides you with another opportunity to post a downloadable CV.

The most important and beneficial aspect of academia.edu is the ability to upload your writings so other scholars can read and cite them. You can host a wide range of writings on your profile from book reviews to fully-fledged articles. You can also upload videos as well as draft papers to receive commentary on them. When uploading materials to the site, be mindful of possible copyright infringements. This is particularly true for your writings that have been published elsewhere, such as in academic journals. Refer to academia.edu’s copyright policy for more information. While the focal point of the website is uploading your writings and reading the work of other scholars, it is not entirely necessary to maintain a vast library of writings on your profile or to have any for that matter, for academia.edu to be an incredibly powerful tool. This is directed, in particular, toward early-stage scholars, like myself, who do not have a substantial portfolio of writings to choose from and upload onto the site. The website’s “follow” function, operating similarly to many social media sites, allows you to curate a list of scholars whose work intersects with your own or you are simply interested in the writings of particular scholars. The “follow” functions allow you to maintain a library of scholars pertinent to your work and provides you with an alert whenever a scholar on your “follow”’ list uploads new content to their page. Academia.edu also provides a useful “message” function that allows you to directly message other scholars to ask questions or discuss specific writings that they have on their profile. The message function also gives you an opportunity, if you follow the previously mentioned steps, to show off your research through your robust profile because, more often than not, they will click on your profile to discover more about you.

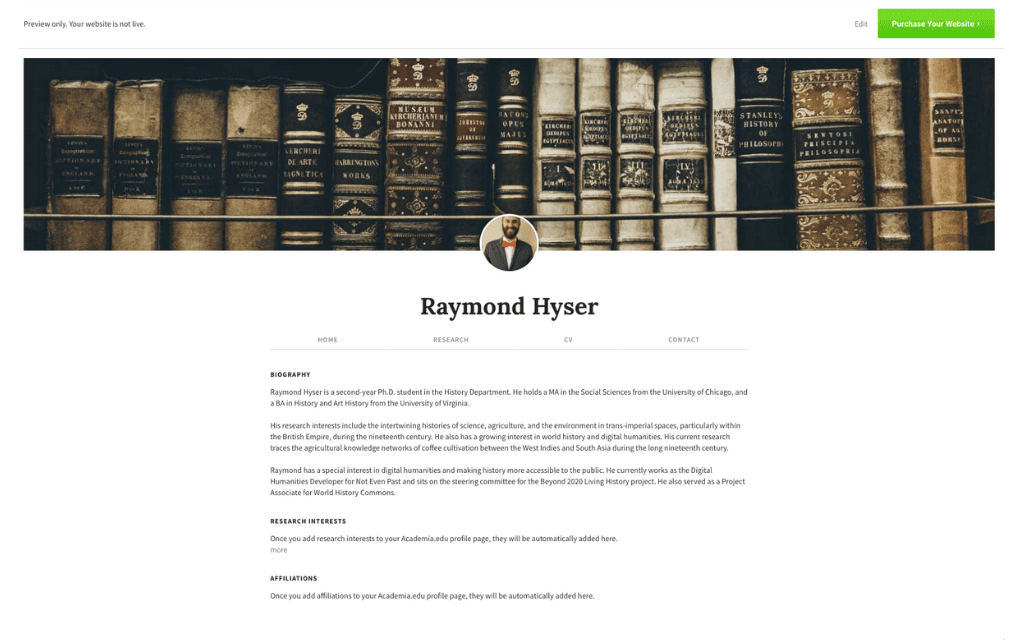

Another benefit to having a premium account on academia.edu is that you get a personal website with a unique website domain of your choosing (if the domain is not taken by another user already). The personal website is significantly more aesthetically pleasing than the profile page that comes with a free account. Your academia.edu website offers a better presentation of your biography and your writings, and also provides a better navigating experience for the viewers who come to your page. That being said, the personal website, like your student profile, has a limited capacity for customization. While academia.edu’s personal website price is particularly low, for only a few dollars more per month you can purchase website building software that provides you with virtually limitless possibilities for curating the best personal website.

3) Personal Website

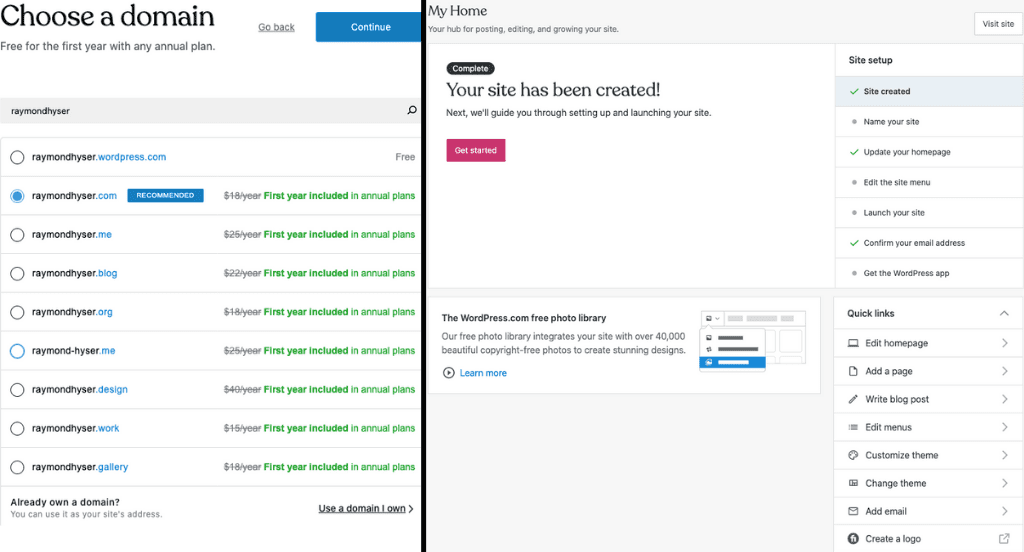

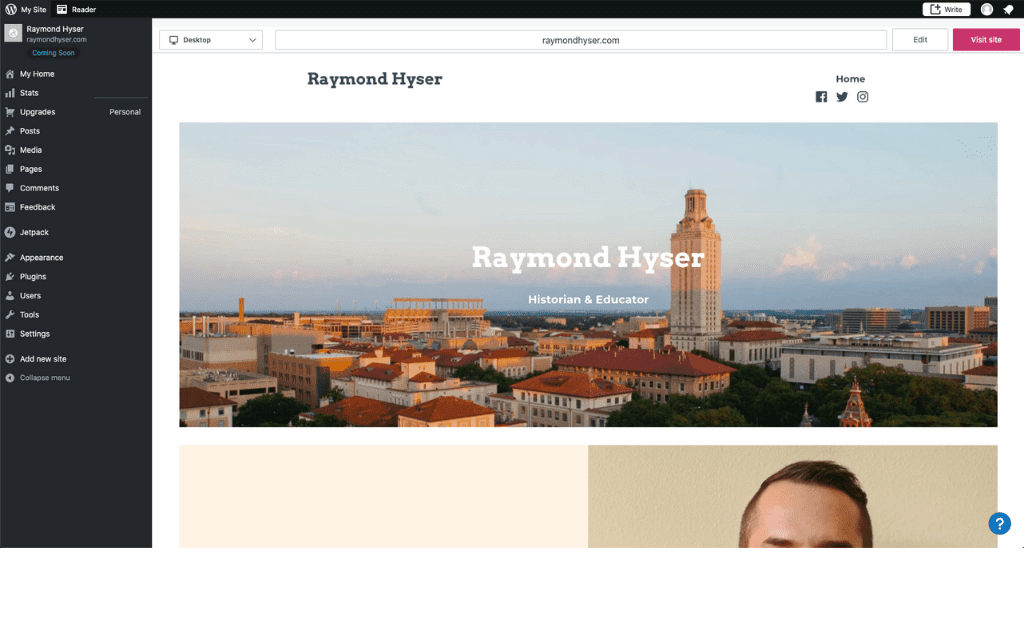

Although a premium academia.edu account allows you to quickly and easily create a personal website, I would recommend spending the extra money on dedicated web-building software to create your personal website. Because website development is a large industry, there are myriad of services and software that you can use to build your website. Given the breadth of options, choosing the right platform for you can be daunting. WordPress, Squarespace, GoDaddy, and Wix are four excellent website builders that provide a robust range of customization tools and are relatively inexpensive. These are three of the most popular options, but the web development space is massive and there are many more alternatives out there. Do not be afraid to Google one that fits your taste, technical skill level, and your wallet. For my personal website, I chose the $8 a month (billed annually) Premium WordPress account.

Once you have selected your website building software, you have to decide on what your domain name will be. Your domain name is the website’s address, often ending in a “.com”. Unless you own a domain name already, you have to pay a yearly registration fee to create a new one. Picking the right name for your website is vital to its success because it will be how someone finds your website on the great expanse of the web. Simply using your name or the title of one of your projects for your domain name are always a safe bet. Once you have your name, you need to decide on what direction you want your website to take. Generally speaking, there are three directions you can take to your website. The first is a generalized personal website that replicates much of the same information found on your student profile and your academica.edu profile, but in a much more aesthetically pleasing way. The second direction is to orientate your website toward a specific research project and the third direction is a combination of the first two options.

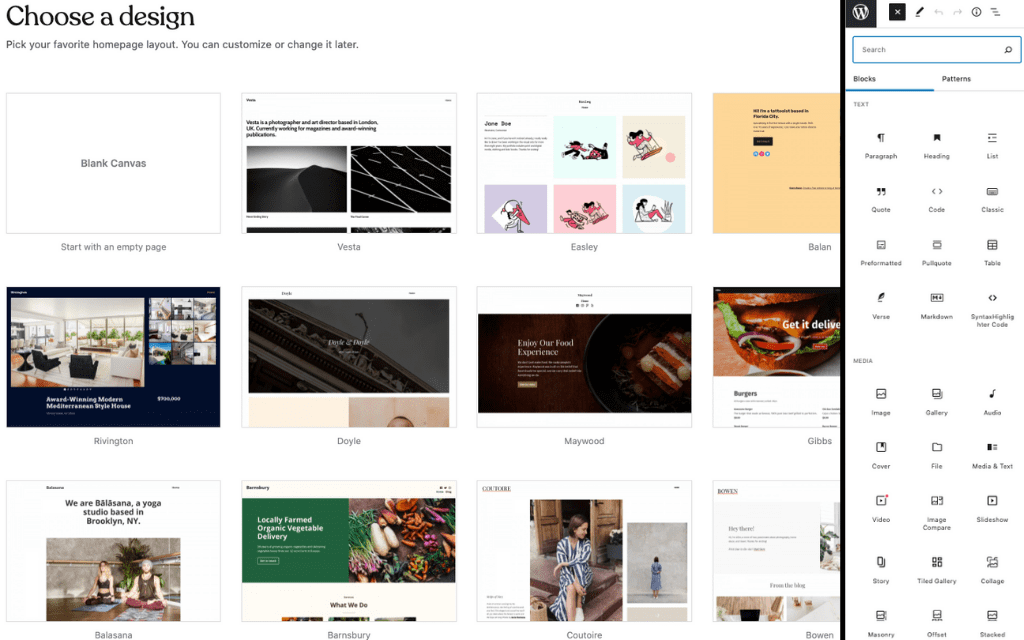

After deciding on which direction you want to take your website, you can start building out your website. Unlike your student and academia.edu profiles that conform to a rigid template, website building tools like Squarespace and WordPress provide you with almost boundless possibilities for customization. Deciding which templates, color schemes, and features you want to incorporate into your website vary considerably from person to person, and you should pick which features you want based on your specific tastes and needs. Although your personal website can take on many different forms, there are still several general components that your website should have. While I am getting repetitive at this point, your website must have your contact information and a biography at the bare minimum. There is no longer a dedicated space to list your research interests like in the previous two steps unless you create one, but it is still important to incorporate keywords that pertain to your research fields into your website as it will help bump your website up in search results. Another key aspect to a successful personal website is hosting a feature that gives viewers a reason to interact with your website and to keep coming back to it. A great way to do this is by writing a series of blog posts that you post regularly on your site. Having a continuous stream of new content, interesting content about your research will give people a reason to come back to your website and gives you an opportunity to show off your research. Additionally, adding teaching and research resources to your website is a great way to generate foot traffic to your website. Curating a library of syllabi, lists of suggested readings and links to digital resources are a few great things to add to your website that will strengthen your site’s content and motivate people to visit your website.

If you follow these three steps you will be well on your way to establishing a strong academic presence online. Google searches will no longer return your cringy MySpace page, but rather several carefully curated sites that illustrate your many attributes as a budding scholar. As the Internet becomes an ever-increasing part of academia, and our lives more generally, it is important to firmly establish yourself online and to leverage all the advantages the Internet has to offer to your benefit.

Addendum – #academictwitter

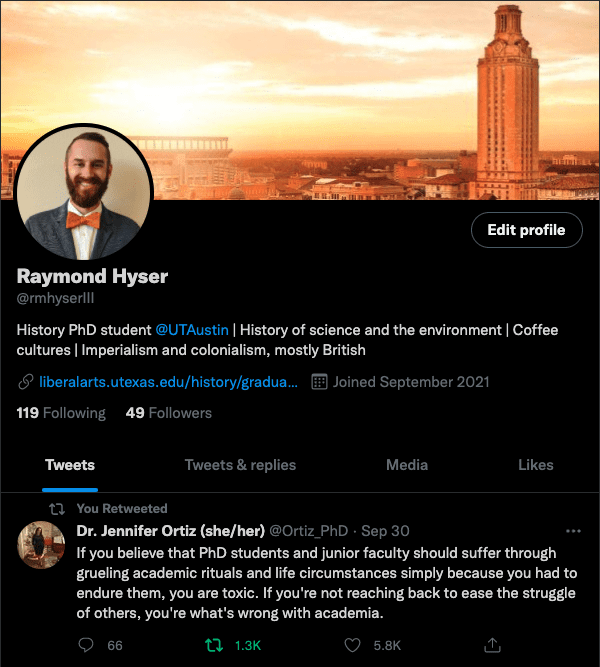

An additional step to take to solidify your academic presence online is creating an account on Twitter and becoming a #twitterstorian. Twitter is a microblogging and social networking service that allows users to write messages (Tweets) and to interact with other users’ content. Creating a Twitter account is as easy as entering a few personal details (name, phone number, etc.) and then choosing your Twitter handle (username). While you can make your handle whatever you want, it is part of your professional identity online and your handle should reflect this. Using your name is always a safe and logical choice. Like in the previous steps, adding a professional photograph for your profile picture is always a good addition to your profile. More important than your profile picture is your Twitter bio. Use your bio to briefly introduce yourself, your affiliations, and your research interests. Your bio is key because if people do not know who you are and what you study, they will not follow you! Since your bio is limited to 160 characters, you can (and should) link a website, such as your personal website, to your Twitter profile so users can learn more about you and your work.

Screenshot of my budding Twitter account

Once your profile is set up, start following other accounts! Twitter is a massive community with tens of millions of potential accounts that you can follow. Initially, you will want to focus your attention on following “high-value” accounts. These include, but are not limited to, influential scholars in your field, professional organizations, publishers, colleagues, and universities. As your Twitter presence gains momentum and you become accustomed to the inner workings of Twitter, you can start curating what accounts you follow to fine-tune what content you want to see on your newsfeed. After your initial round of account following, you should turn your attention to the bread and butter of Twitter: Tweeting. Tweets are a great way to share your ideas, provide research updates, and engage with fellow #twitterstorians. Since Tweets are limited to 280 characters or less, Tweeting is also a terrific exercise in developing a writing style that is brief and to the point. Twitter is a tremendously powerful tool that offers scholars the opportunity to showcase their research and network with academics across the world. Creating a Twitter account is a great way to further cement your academic presence online.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.