By Adam Clulow and Tom Chandler

The Virtual Angkor project aims to recreate the sprawling Cambodian metropolis of Angkor at the height of the Khmer Empire’s power and influence in the twelfth century. A collaboration across disciplines and technologies, it has been built from the ground up by a team of Virtual History Specialists, Archaeologists and Historians at Monash University in Melbourne, Flinders University in Adelaide and The University of Texas at Austin across a period of more than ten years.

Although it has been used for research, Virtual Angkor was constructed specifically for the classroom and can be used at both secondary and tertiary level. It deploys advanced Virtual Reality technology, 3D Modeling and Animation to bring a premodern city to life, to place students on its streets and allow them to interact with a historical environment.

Angkor and the Khmer Empire

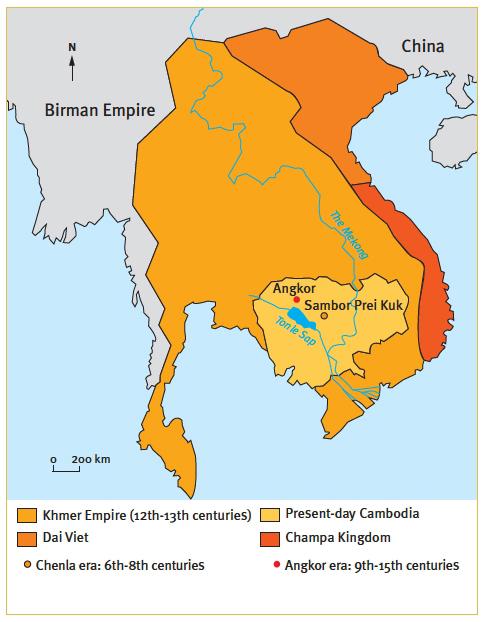

For approximately 500 years from the ninth to the fifteenth centuries, the Khmer empire dominated the politics and economy of Southeast Asia. Located in modern day Cambodia, it was unique in the history of the region, extending direct influence across a vast swath of territory, encompassing most of present-day Thailand and the southern provinces of Laos and Vietnam.

Today, the Khmers are most famous for the remarkable architectural sites they left behind. Stretching over some 400 square kilometers, the Angkor Archaeological Park in Cambodia contains the remains of successive capitals of the Khmer Empire including an extensive network of stone temples. Together, these form one of the most important archaeological sites in Southeast Asia. At its peak in the twelfth century, the city is estimated to have been home to around three-quarters of a million people. This means that Angkor was, in the words of one archaeologist, “the most extensive city of its kind in the pre-industrial world.”

While the name Angkor conjures up immediate images of crumbling stone temples in a verdant jungle, reconstructing the city represents a huge challenge. Apart from inscriptions on temples, no written records from the period have survived the ravages of time and the monsoonal environment. The more important source comes in the form of extensive archaeological surveys of Angkor undertaken by the French School of Asian Studies (École française d’Extrême-Orient), the Greater Angkor Project, and the Khmer Archaeology Lidar Consortium. Together, they have produced detailed, multilayered maps of temple complexes, rice fields, roads, canals and settlement mounds throughout the Angkor Archaeological Park. These surveys provide the spatial foundations for any subsequent reconstruction of the city’s architectural and environmental landscapes. For written sources, historians rely especially on observations made by Zhou Daguan, a Chinese official dispatched to Angkor in 1296 by the Temur Emperor, who produced a detailed account of the city and its inhabitants.

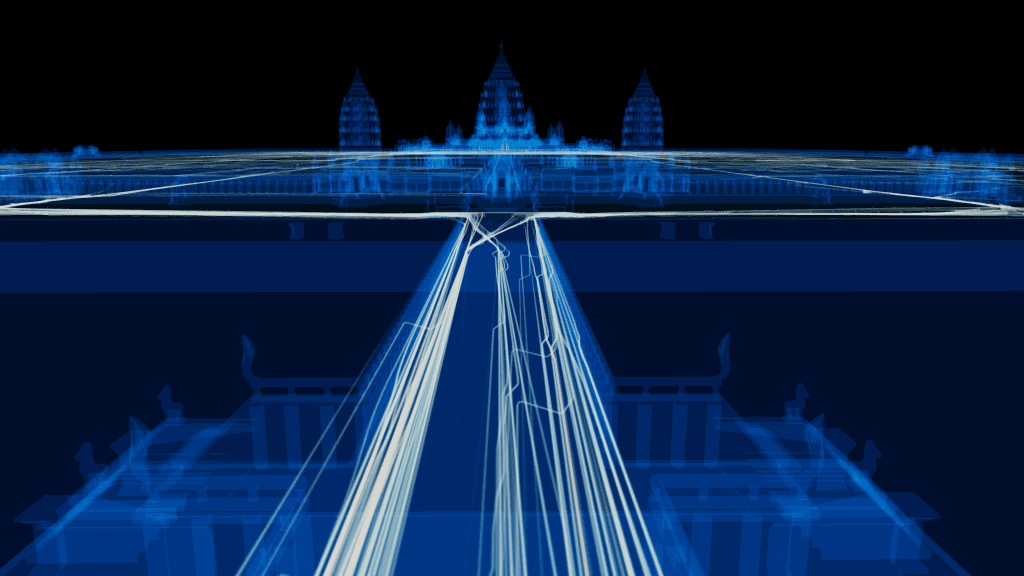

Teaching

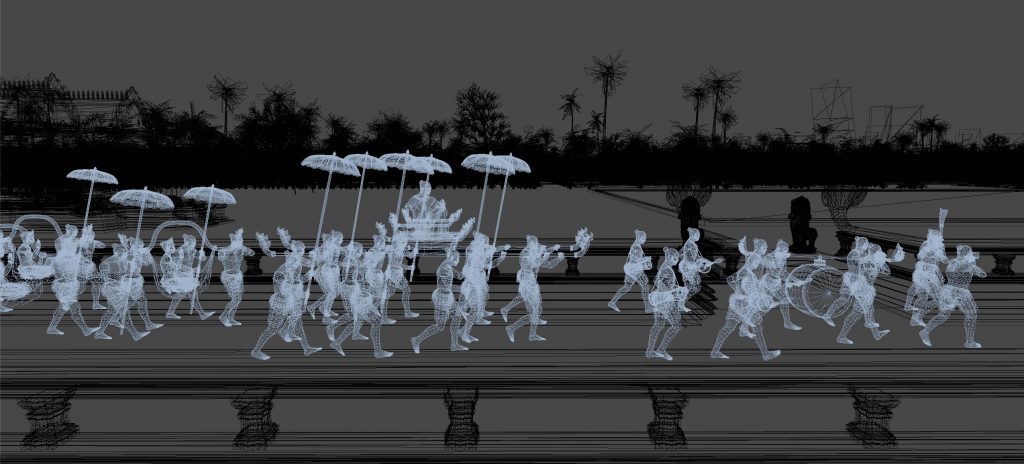

Most Asian history survey courses make reference to Angkor but the standard black and white illustrations contained in textbooks make it difficult for students to gain a sense of the scale and grandeur of the city. The Virtual Angkor project allows educators to place students inside the Angkor Wat complex, to view the famous bas-reliefs first hand without leaving their seats, to sail down one of the hundreds of canals crisscrossing the city, to inspect a marketplace selling goods from across Southeast Asia and to watch as thousands of animated people and processions enter, exit, and circulate around the complex.

The project, which went online in January 2018, can be experienced in multiple ways, through Virtual Reality headsets, online 360° videos that provide a glimpse into the city, short animated scenes that highlight episodes in the daily life of Angkor, and interactive teaching modules.

The most immersive experience comes via a Virtual Reality headset combined with earphones as the project includes multiple soundtracks of the environment complete with music, snatches of conversation, and sounds of daily life. The experience can be dizzying for students who jump to move aside as processions pass, who experience vertigo as they look down from elevated structures, and who become aware of the sun slowly rising in the sky above them.

While such equipment is usually available in university laboratories, it is also bulky and expensive. As a result, Virtual Angkor is designed to be accessed using student’s smartphones. In History classes, with their focus on close analysis and discussion, the phone is often seen as the enemy of the instructor, a source of distraction and diversion from the material at hand. But it can also be turned into a key educational tool. In this case, Android phones can be paired with relatively crude headsets such as Google Cardboard, which can be purchased for less than $20, to create an immersive environment. In addition, students can interact with the project via 360° panoramas which enable them to look around the city from the particular stationary point or by watching short 15-20 second animated scenes.

The site also includes a series of interactive modules focused on three themes: Architecture and Power, Water and Climate, and Trade and Diplomacy. These use the technology as a jumping off point for more conventional historical enquiry. To cite one example, students can look around a thriving marketplace in the city before making use of primary and secondary sources to consider how Angkor was integrated into wider networks that stretched across the region. For this particular week, the site combines a visualization of the marketplace with Zhou Daguan’s description of “sought-after Chinese goods” and an important article on Chinese ceramics in Angkor. These combine to push students to reassess the place of Khmer merchants and consumers in regional networks of trade.

Viewed as a whole, the Virtual Angkor project represents an attempt to harness advances in technology to create an immersive environment that allows students to use their phones to experience one of the great cities of Global History. Moving forward, its broader goal is to take the site and its underlying technology to new audiences via a partnership with Ubisoft, a video game company famous for its construction of elaborate historical environments, and a traveling IMAX exhibition that will move between multiple cities.

Further Reading

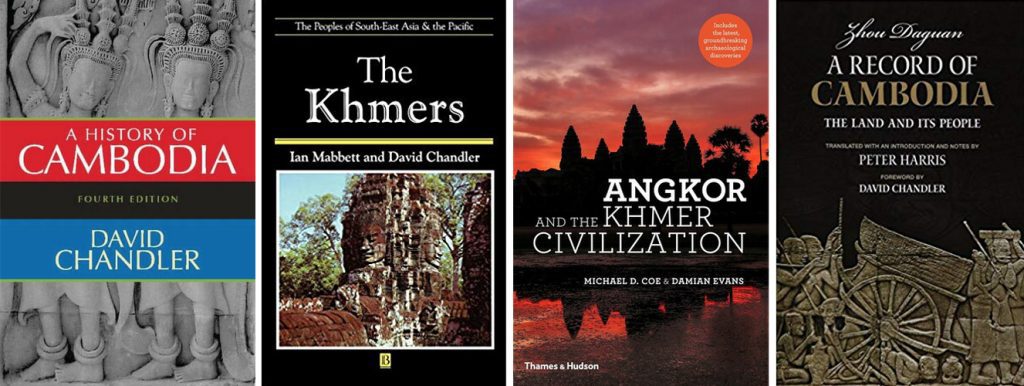

David Chandler, A History of Cambodia, 4th Edition (2008).

The definitive general history book on Cambodia from ancient times to the 21st century written by the foremost scholar in the field.

Michael Coe and Damian Evans, Angkor and the Khmer Civilization (2018)

A concise survey of Cambodian history from the beginning of recorded Khmer history to the expansion of French colonialism into Cambodia in the 18th century.

Damian Evans, Christophe Pottier, Roland Fletcher, Scott Hensley, Ian Tapley, Anthony Milne and Michael Barbetti, “A comprehensive archaeological map of the world’s largest preindustrial settlement complex at Angkor, Cambodia,” Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences of the United States of America 104, no. 36 (2007): 14227-14282. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0702525104

The most extensive exploration of the geography of Angkor, which was developed through a combination of decades of on-the-ground mapping surveys with cutting-edge remote-sensing technologies developed in conjunction with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and NASA.

Adam Clulow and Tom Chandler, “Modeling Virtual Angkor: An Evolutionary Approach to a Single Urban Space,” IEEE Computer Graphics & Applications, Volume 40, Issue 4 (2020), 9-16

Roland Fletcher, Damian Evans, Christophe Pottier, Chhay Rachna, “Angkor Wat: An Introduction,” Antiquity 89, no. 348 (2015): 1388-1401. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2015.178

A brilliant introduction to a special series of articles dedicated to exploring the latest developments in archaeological research on Angkor Wat and its surroundings.

Ian Mabbett and David Chandler, The Khmers (1996).

An authoritative monograph covering 2,000 years of the Khmer people and their culture.

Zhou Daguan, A Record of Cambodia, The Land and Its People, trans. Peter Harris (Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, 2007)

A first-hand account written by the Chinese diplomat, Zhou Daguan, describing his stay in Angkor from 1296 to 1297. Offers a tantalising glimpse into the intricacies of Khmer society from the eyes of an outsider.

Andrew M. Koke, “Virtual Reality in the Classroom: How Historians Can Respond,” Perspectives on History, Oct. 1, 2017.

Virtual Angkor images: Tom Chandler and Mike Yeates, SensiLab, Monash University