by Kate Grover

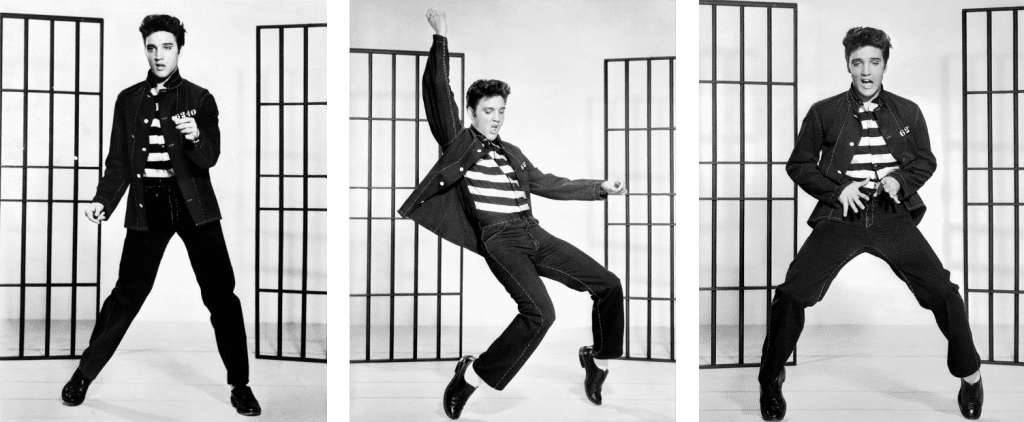

Elvis Presley promoting the film Jailhouse Rock, 1957 (via Wikimedia Commons)

When I was nineteen, I was bestowed with some of the highest praise a person can receive.

It happened at a rehearsal for The Vagina Monologues (go figure…) when some cast members I hadn’t met approached me for the first time:

“You’re Kate, right? Cool Kid Kate?”

“What?”

“Cool Kid Kate. There’s another Kate in the cast, so we’ve been calling you that to know which one we’re talking about.”

I was stunned. “Wow. Thank you,” was all I could say. We talked for a few more minutes, but at that point, I had completely checked out of the conversation. The compliment pinballed around my brain, igniting pleasure centers that I didn’t even know existed.

Cool kid Kate. Cool kid Kate. Ohmigosh…that is so cool!

This anecdote highlights a more-or-less universal truth: cool—as a concept, a descriptor, and a category—is potent force. For me, hearing someone say I was cool was much-needed validation, reassurance that the way I was living, acting, and being in that moment was acceptable. Better than acceptable—cool!

But while I had no doubt what cool meant to me, it remains an elusive concept. What is the mysterious power of cool? And where does it come from?

Believe it or not, scholars have been asking these questions for the last thirty years. Since the late-1980s, several writers have attempted to define cool and position it as a distinctly American concept. In the 1940s, African-American jazz musicians first popularized cool as a way of describing both the new, more restrained style of jazz and a form of emotional and aesthetic self-possession. For example, jazz saxophonist Lester Young, the figure scholars most widely cite as the first to bring cool into American vernacular, used the phrase “I’m cool” to communicate being in control and relaxed. Cool was different from hip, another staple in the lingo of African-American jazz culture, which meant being streetwise and aware of new trends and ideas.

Lester Young in New York, 1946 (via Flickr)

Though cool and hip have similar roots, it is important to distinguish these two concepts and validate their specific meanings in postwar African American culture. At the same time, it is also important to recognize that, for many people in decades past, cool and hip have come to mean the same thing: what is new, what is now, and what’s in vogue. Consequently, some of the early scholars studying cool have used the term in different ways. Two of the first major studies to explore ideas about coolness, by Richard Majors and Janet Mancini Billson, and by Peter N. Stearns use cool to connote a specific way of being—a usage akin to the meaning of cool promoted by 1940’s jazz artists. Conversely, Thomas Frank and Susan Fraiman rely on a formulation of cool that reflects its conflation with hip. While these early texts provided the groundwork for later studies, their diverging approaches and lack of consensus on cool’s origins and function in American life meant that cool remained an obscure area of scholarly research for quite some time.

Joel Dinerstein and Frank H. Goodyear’s 2014 book American Cool, has played a major role in popularizing, legitimizing, and catalyzing the scholarly study of cool. Published as a companion to the exhibition Dinerstein and Goodyear curated for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, American Cool examines what it means for someone to be cool. The study introduces cool as an American concept, theorizes how cool acts as a marker of distinction, and showcases portrait photography of “cool figures” throughout American history—the same portraits that appeared in exhibition. But most importantly, the study outlines the ways these cool figures (mainly iconic politicians, musicians, or actors) provide us with new, innovative ways of being. According to Dinerstein, cool people are important to Americans because they teach us methods for living life that we would have not otherwise known. Cool figures are special among ordinary people because they take what other cool people before them have done and transform that into something new for subsequent generations. People emulate cool figures and new forms of coolness develop that provide even more people with models for being that enliven and inspire. Cool, in this construction, is a way of describing someone you admire for being and doing something you could not do and be on your own. This explains, perhaps, why the quippy compliment “Cool Kid Kate” meant so much to me.

Joel Dinerstein and Frank H. Goodyear’s 2014 book American Cool, has played a major role in popularizing, legitimizing, and catalyzing the scholarly study of cool. Published as a companion to the exhibition Dinerstein and Goodyear curated for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, American Cool examines what it means for someone to be cool. The study introduces cool as an American concept, theorizes how cool acts as a marker of distinction, and showcases portrait photography of “cool figures” throughout American history—the same portraits that appeared in exhibition. But most importantly, the study outlines the ways these cool figures (mainly iconic politicians, musicians, or actors) provide us with new, innovative ways of being. According to Dinerstein, cool people are important to Americans because they teach us methods for living life that we would have not otherwise known. Cool figures are special among ordinary people because they take what other cool people before them have done and transform that into something new for subsequent generations. People emulate cool figures and new forms of coolness develop that provide even more people with models for being that enliven and inspire. Cool, in this construction, is a way of describing someone you admire for being and doing something you could not do and be on your own. This explains, perhaps, why the quippy compliment “Cool Kid Kate” meant so much to me.

The American Cool exhibition and its glossy-yet-scholarly coffee-table book companion attracted media attention and public interest to the study of cool. In particular, news outlets focused on Joel Dinerstein, the educator who had been teaching college courses on cool decades before the American Cool exhibition. Dinerstein has subsequently become the most prominent—and in-demand—scholar working on cool today. In 2014, writers at TIME consulted Dinerstein for their “coolest person of the year” series. A couple years later, the fashion brand Coach asked Dinerstein to write a book celebrating the company’s 75th anniversary. This year, Dinerstein published the first cultural history of cool in the Cold War era, The Origins of Cool in Postwar America. As the title suggests, this nearly 400-page text is American cool’s origin story and gives the most comprehensive research on cool’s roots to date.

But the study of cool is far from complete. There are many more questions to ask, especially about what cool means to different groups of people in the U.S. today. Is cool still important to people? How does cool change in different environments? Who gets to be cool, and why? The answers to these questions promise to reveal major insights about American life and culture.

Further Reading by Joel Dinerstein:

“Hip vs. Cool: Delineating Two Key Concepts in Popular Culture,” in Is It ‘Cause It’s Cool? Affective Encounters with American Culture, ed. Astrid M. Fellner et al. (2014)

“Lester Young and the Birth of Cool,” Signifyin(g), Sanctifyin’, & Slam Dunking: A Reader in African American Expressive Culture, ed. Gena Dagel Caponi (1999)

With Frank H. Goodyear III, American Cool (2014)

Coach: A Story of New York Cool (2016)

The Origins of Cool in Postwar America (2017)

Other sources:

Joel Stein, “The Coolest Person of the Year,” TIME, December 11, 2014.

Richard Majors and Janet Mancini Billson, Cool Pose: The Dilemmas of Black Manhood in America (1992)

Peter N. Stearns, American Cool: Constructing a Twentieth Century Emotional Style (1994)

Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counter Culture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (1997)

Susan Fraiman, Cool Men and the Second Sex (2003)

You may also like:

Dorothy Parker Loved the Funnies by David Ochsner

Nakia Parker talks pop culture in the classroom

Karl Hagstrom Miller on segregating Southern pop music