by Jacqueline Jones

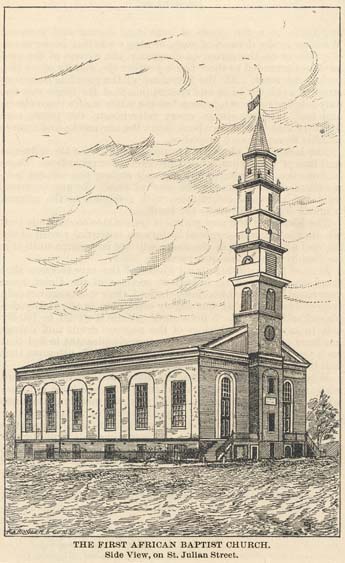

December 31, 1862 fell on a Wednesda, and that night members of Savannah’s First African Baptist Church held their traditional New Year’s Eve “watch meeting.” Each year members of the congregation gathered on this night to welcome the new year and to ask for God’s blessing on the city’s African-American community. Such “watch meetings” or “watch night” services were held all over the country, linking African Americans in Savannah with communities in Richmond, New York, Boston and elsewhere. After a year and a half of a bloody civil war, the community in Savannah consisted of about 10,000 enslaved men and women, 1,000 free people of color, and several hundred enslaved workers brought from all over the state of Georgia to dig trenches and otherwise toil at the direction of Confederate military authorities.

Outwardly, the “watch meeting” that night seemed unremarkable, the prayers and songs customary for this type of service of celebration. Soon after midnight, the worshippers exchanged greetings with one another, and then parted. The service had proceeded peacefully, undisturbed by city officials. And yet secretly among themselves the members of First Baptist had just celebrated a promise of freedom: the Emancipation Proclamation to be released by President Abraham Lincoln the next day, January 1, 1863.

One of the participants, James Simms, considered the service a miracle of sorts, a quiet affair honed by long years of verbal restraint and by one hundred days of painful anticipation. Looking back, Simms recalled his inability to speak openly of his yearnings for freedom during slavery times: “The tongue must be dumb upon that theme; it was the soul that sung.” That night the choir offered up familiar hymns of worship and thanksgiving; only in their hearts did these “gospel trumpeters” herald “the year of Jubilee,” for, according to Simms, the music of the soul “was not for earth’s ears, but it was heard in heaven.”

On New Year’s Day, black clergy from all over the city held another celebratory but equally subdued gathering, a dinner. This ecumenical gathering featured prayers that “God would permit nothing to hinder Mr. Lincoln from issuing his proclamation” that day. Of the dinner itself, we know little more, except that James Porter, choirmaster and warden of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, “delivered an excellent address on the proclamation”—an address recounted by the anonymous author of Porter’s obituary, published thirty-two years later.

How did these black preachers and church congregants learn that President Lincoln would announce the Emancipation Proclamation on the first day of January? Simms implied that he and others knew of Lincoln’s September 22, 1862, public statement that he intended to issue such a proclamation on January 1; hence their “one hundred days of painful anticipation.” In all likelihood from early 1862 onward, the Savannah black community kept informed of national political and military events via the Union forces occupying Fort Pulaski and nearby Tybee Island, just eighteen miles down the Savannah River. Black refugees, fugitives from slavery, were fleeing from the interior of the state and from Savannah, seeking safety along the coast, where Yankee gunboats were patrolling the waters. As early as the summer of 1862, some male runaways had joined the Union navy, and colonies of self-sufficient refugees had begun marketing fish, eggs, and vegetables to the occupiers and the gunboat crews. With Confederate deserters running from the coast, and black men, women, and children making their way downriver, the border between southern and Union-held territory remained porous. Spies, scouts, messengers, and runaways all conveyed information back and forth between Savannah and the federal forces not far away.

Not far from Savannah, on Port Royal Island, South Carolina, U. S, military officials held their own grand affair to mark New Year’s Day and the proclamation. Gathering together were white and black troops, an estimated 3,000 black men and women civilians, teachers of the freed slaves, and visiting dignitaries from the North. The crowd feasted on ten oxen roasted the night before, and washed down the meal with a mixture of water, molasses, vinegar, and sugar. One highlight of the affair came when, during the ceremonies, an elderly black man and two women spontaneously burst into song, singing “My country ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty”—an unscripted moment that momentarily caught the white onlookers by surprise. The other highlight came when two Sergeant Prince Rivers and Corporal Robert Sutton, who just a few months ago had been slaves, delivered brief remarks to the crowd.

Meanwhile, back in Savannah, whites sensed foreboding. In the words of one Confederate officer, the day was “filled with disquietudes.” Huge winter battles were taking a tremendous toll on the South, and single clashes were costing both sides many thousands of casualties. Even the most defiant Confederates—and there were many in Savannah—could see no end to the carnage. By this time the local papers were offering rewards for large numbers of runaways; these notices called for the capture and return of not only fugitive slaves, but also Confederate deserters, men who abandoned their posts out of fear for their lives, and out of resentment over the high price paid by ordinary recruits, in contrast to the wealthy buyers of army substitutes.

The war would wage for another long, bloody year and a half, and most Georgia blacks would remained enslaved for another year, until General William T. Sherman and his troops – aided by thousands of black people themselves — liberated Savannah in late December, 1864. Nevertheless, the Emancipation Proclamation marked a turning point in the conflict, and a beacon of hope that freedom was nigh for African Americans all over the South.

More on the Emancipation Proclamation on Not Even Past:

George Forgie, “Work Left Undone: Emancipation was not Abolition”

Laurie Green, “1863 in 1963”

Daina Ramey Berry, “Unmixed Blessin'”? A Historian’s Thoughts on Django Unchained“

Nicholas Roland on Spielberg’s Lincoln

You may also enjoy:

Jacqueline Jones on Civil War Savannah