How does a humanist become a digital humanist?

Dr. Ece (pronounced “A.J.”) Turnator talks with us about her work in digital history. She earned her Ph.D. in Byzantine History at Harvard University in 2013 and is currently curator of the Global Middle Ages Project and is a CLIR (Council on Library and Information Resources) and The A. Mellon Foundation postdoctoral fellow in Medieval Data Curation at the English Department and UT Libraries. In the Fall 2015, she will teach Introduction to Byzantine History in the UT History Department. My conversation with Dr. Turnator offers insights into the challenges and the exciting new possibilities that the digital era brings to scholarship in history and more broadly in the humanities.

During her graduate training Turnator became interested in the workings of the digital world. She studied with Prof. Michael McCormick on the Digital Atlas of Roman and Medieval Civilizations (DARMC), a project that makes materials for a Geographical Information System (GIS) approach to mapping and spatial analyses of Roman and Medieval civilizations freely available on the internet. She became the assistant project manager of DARMC, a seminal experience that introduced her to new ideas and methodologies that ultimately helped shape her own research and dissertation.

By the time Turnator started to explore these digital tools, she, like other students, had been seeking training on her own and trying to figure out what tools were best suited to her research. She initially learned how to utilize GIS through workshops that gave her a sense of the scope and potential of the tool. She felt that she needed more than what occasional workshops had to offer and began to take courses in digital methodologies. She recommends that students take advantage of the resources at UT, and take an introductory course in digital humanities (offered at the iSchool) in order to get a proper overview of the methodologies available to them. This advice is relevant no matter what area of the humanities one might be interested in. Turnator explains, “In general, I don’t think we ought to divide digital humanities into departments because the questions asked and the tools used can be deeply relevant no matter which specific humanities field we happen to be in.” Data visualization tools and text analysis tools can be useful to anyone in the humanities, she asserts, “These tools can productively shape research, depending on what questions we pose.”

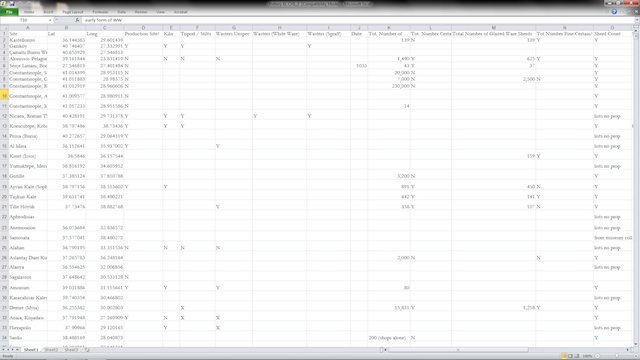

For example, in her dissertation research about Byzantine economy, Turnator worked with large amounts of data involving archaeological artifacts, ceramic, coins, and textiles. In trying to understand the distribution patterns of ceramics across what is today Western Turkey and Greece, she built a table of ceramic types and mapped them by site. She was able to notice patterns that were difficult to see by using traditional methods and these insights changed the course of her subsequent research.

Excel Table showing data on Fine Ceramic types derived from sites studied in Turnator’s Dissertation

The Global Middle Ages Project (a much expanded site is under development) started in 2007 by Prof. Geraldine Heng from UT Austin and Prof. Susan Noakes at the University of Minnesota, aims to become a generator of new ideas and questions about the global Middle Ages and work as a tool for graduate students, scholars, and the general public to reflect and learn about the medieval world beyond Europe. In 2013 under the leadership of Dr. Fred Heath, the Vice Provost and Director of UTL, the libraries became a partner of the project. Currently, the new GMA site is being built utilizing the expertise in the libraries. One of the site’s projects in the pipeline is called Virtual Plasencia. Prof. Roger Martinez (U. of Colorado, Colorado Springs) and Dr. Victor Shinazi’s (ETH Zurich) and an international team are working on a 3D redesign of the city in northwestern Spain today. One of the biggest challenges of this and other digital projects, according to Dr. Turnator, is to not replicate our analog habits but to learn to benefit from being in the digital world by understanding how it actually works, and what its limitations are.

There are five other projects in the GMA pipeline:

- Lynn Ramey and her team’s (Vanderbilt University) “Discoveries of the Americas

- Chapurukha Kusimba (American University) and his team’s “Early Global Connections in East Africa”

- Timothy Pauketat (Urbana-Champaign) and his team’s “The North American Middle Ages: Big History from the Mississippi Valley to Mexico”

- Christopher Taylor’s (Williams College) “Peregrinations of Prester John: The Creation of a Global Story Across 600 Years”

- Nükhet Varlık (Rutgers University) and Abdurrahman Atçıl’s (Queen’s College, CUNY) “A Prosopographical Study of Sixteenth-Century Ottoman Medical Elite”

- Thomas Kealy’s (Colby-Sawyer College) “Itinerary Poets in Thirteenth-Fourteenth-Century-Al-Andalus

Another challenge that Dr. Turnator faces right now on the Global Middle Ages project is establishing consistent searching tools for the diverse projects that are and will be in its network. It is necessary but difficult to produce “metadata standards,” that is, categories for indexing content that most medievalists can agree upon so that users can find what they’re looking for on a large network of websites. To that end, she is organizing a workshop funded by CLIR, the Mellon Foundation and UTL, to bring medievalists to UT Austin for a two-day workshop in May 2015. The purpose of the meeting is for medievalists, librarians, and technologists to discuss medievalists’ workflow in research, publication, and teaching. Turnator explains that “the biggest challenge in digital anything is that it absolutely requires collaboration with librarians and other stakeholders on campus to succeed in the long run.” Librarians are experts in long-term preservation, access and in dealing with what are called data-interoperability issues, or the problems that come up when online content is created without consistent standards of data description and definition. That is why having one foot in the libraries and one foot in a humanities department has been so useful for Turnator and for the projects she works on.

Digital Humanities is increasingly becoming a desired and expected skill set for humanists. Job openings at the MLA (Modern Language Association) and AHA (American Historical Association) are increasingly requiring this skill set. Nationwide, humanities departments have begun to incorporate courses to accommodate these emergent needs. At UT, Turnator points out, the School of Information (iSchool) has fantastic resources and courses relevant for humanities students; workshops are available at UT Libraries, TACC (Texas Advanced Computing Center), Digital Writing and Research Lab (DWRL), to name a few. So UT has great resources but they may be difficult to navigate for humanities students in their fields trying to fulfill their department-specific requirements.

Turnator also shared her views about how she sees the digital humanities evolving and affecting scholarship. Projects in the digital humanities, she explains, challenge traditional ways of doing scholarship, especially the single author/monograph model. We do not yet have a well-oiled review processes to evaluate digital projects, which are often collaborative, and hiring committees often do not understand where credit is due and tend to ignore them completely in the hiring process; that will change as the field matures. For now good digital humanities projects bring mostly good publicity and fame to established scholars. In the future, formal training will not only help graduates get jobs but will also help forge the path that leads to peer-review and publications that help faculty get promoted based on valued digital projects. She adds “the acquisition of digital skills require formal training and careful study.” We need to train a new generation of humanists who not only know how to build digital projects but also how to evaluate and utilize them. Formal training in these methodologies should be front and center, and just as the methodologies tend to be naturally collaborative, this type of training needs departments, research units, and libraries to bring their expertise to the table and collaborate. When this happens, digital methodologies have the potential to change the world of humanistic inquiry in the long term.

Catch up on the latest from the New Archive series:

Maria José Afanador-Llach discussed her experience at a Digitilization Workshop in Venice and Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web

Charley Binkow discussed digitalized images from the Folger Shakespeare Library

Charley Binkow explored photographs of California’s Gold Rush

Henry Wiencek found a digital history project that not only preserves the past, but recreates it

All images courtesy of Ece Turnator