By Sumit Guha

Slavery is an old and tenacious institution in human society. It is not unknown at present. Nor was it confined in the past to the plantations in the Americas that fed world trade after Europe’s overseas expansion in the 1500s. The practice was widespread in India and accepted and regulated by every regime extant in the region. The English East India Company was well acquainted with slavery and the slave-trade. In 1685 it directed its agents at the port of Karwar to buy 20 to 40 slaves at about £ 2 per head, adding that since the area was overrun by rival armies, it might even be possible to get them for a quarter of that price. Most high-status households owned slave-women and often gifted them to each other or their superiors. Slaves not only did unpaid work for their owners, they were themselves commodities, bought, sold, and gifted. This is the story of one vulnerable young woman who successfully fought her way out of such a transaction.

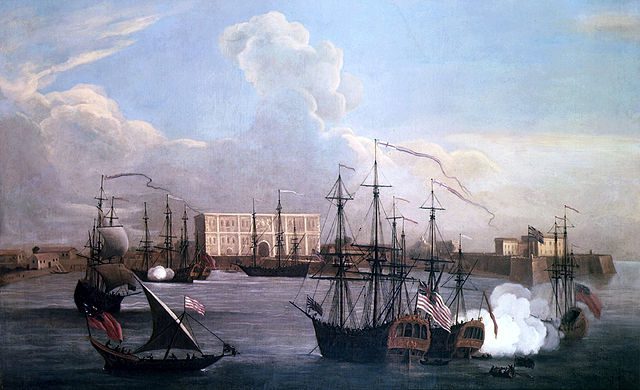

Painting of the East India Company’s settlement in Bombay and ships in Bombay Harbour 1732-33. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The young woman whose petition came before the Mayor’s Court on April 24, 1726, in the small British colony in the former Portuguese territory of Bombay (today’s Mumbai), had already led a life full of travail and adventure. By her account, she was born to Hindu (she used the Portuguese term ‘Jentue’) parents in Versova, a fishing settlement that the King of Portugal had bestowed on an unnamed lord. The death of her parents threw her into the hands of the said lord, who immediately had her baptized a Christian and then after some time, married her to a tenant farmer named Manuel.

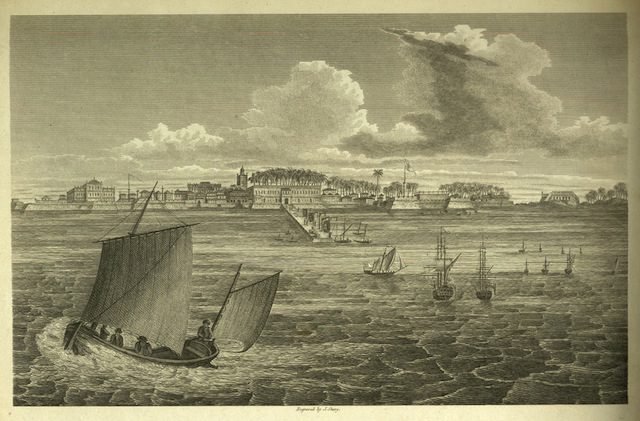

View of Bombay from Colaba island in 1773 by James Forbes. Engraving Date, 1813. Courtesy of Old Photos Bombay.

This practice of taking charge of orphans was a part of the European heritage of both feudal and Roman law. The great digest of Justinian (c.600 CE) directed that pagan minors be placed under Christian tutelage in the hope of saving their souls from hell. Feudal law also stipulated that a minor heir became a ward of his or her lord (up to the King). The logic was that he or she might otherwise be controlled by the lord’s enemies – or worse, marry one of them. The right to manage the lands or marry off an heir was also a profitable one and a source of revenue to the lord.

Manuel, our young woman’s new husband, treated her “very ill,” though no details were recorded. Versova was not far from the growing city of Bombay. It is today a suburb of high rises but the fishermen and fishwives there still retain a tenacious hold on their original settlement. Salted fish hang out to dry and boats still return with their catch at dawn.

We do not know how the woman, now named Anna D’Souza, got to Bombay, but once there she began living with an immigrant from Portugal named Joseph D’Coasta (probably a corruption of the Portuguese Da Costa). D’Coasta enlisted in a company of soldiers commanded by a Captain Douglas, stationed in Tellichery (Thalassery today), a trading port where the Portuguese had built a fort to control the pepper trade of the region. By this time it had passed into Dutch hands and then to the English East India Company. D’Coasta was shot through the heart while on duty at this outpost. And at that point his commander claimed that Anna was actually D’Coasta’s slave-concubine, not his wife, and that as the deceased owed his captain money Anna was now the captain’s. Douglas thereupon seized Anna and shipped her to Bombay for sale. She was sold to a Captain Button and then to a whole series of other men, the last of whom, Mr Garland, “pretended to give her away” to a Captain Baynton, who was now insisting that she was rightfully his slave. Anna managed to petition the Court saying that if she had not been falsely cast into slavery she “might be well married.” It could be that her suitor helped her reach the court despite the obvious interest of a whole series of English army officers in denying her freedom.

The court examined evidence and witnesses and declared that she had not been a slave “at least since she came upon this Island.” Therefore her first sale by Captain Douglas was illegal and unwarrantable and so he was liable to pay damages to the last “owner” Garland, whose lawyers claimed the sum of 170 rupees or about £20, a considerable sum at that time. Anna D’Coasta finally secured her freedom and may even have married well as she had anticipated.

Slaves lacking kinship ties would need to find protectors if they were to survive in the predatory world of the day. Anna may have found one. An 18th century document in the archives of the Maratha kingdom contains a complaint from one Dattaji Thorat that his slave-woman had fled to the royal capital of Satara and was being sheltered by a powerful person there. The latter threatened Thorat with violence when he sought to recapture her. Maybe Anna had found a similar protector? We do not know the rest of her story, one of the many obscure lives briefly glimpsed in the archive and then known no more.

For more on slavery in colonial and pre-colonial India

Indrani Chatterjee, Gender, Slavery and Law in Colonial India (Oxford University Press, 1999)

Indrani Chatterjee and Richard M. Eaton eds. Slavery and South Asian History (Indiana University Press, 2006)

You may also like:

Sumit Guha’s Giving a life, winning a patrimony

Sumit Guha Beyond Caste: Power and Identity in South Asia, Past and Present (2013)