This essay comes to Not Even Past from a student in the Pace-GLI Master of Arts in American History. For more on that program, see Prof Madeline Hsu’s blog on the UT History faculty who teach on-line classes for it.

by Michael Louis Agovino

Language alone cannot capture the lived experience of the immigrant. The writer Albert Camus describes traveling to a new land as fear in and of itself. In his diaries from 1935-1941, Camus conveys the angst one encounters when arriving on the shores of an unfamiliar place. Conceivably, this is how Thomas Lonergan, his pregnant wife Alice Tobin, and their two-year-old daughter Catherine felt when they arrived in Castle Garden, New York City’s first immigration center. Leaving behind a place of comfort, family, and linguistic comradery must have tempted the Lonergan family to return home. In New York, the Lonergans were the “other” and had to navigate what it meant to be alien.

Alice, pregnant with her daughter Ellen, must have felt a whirlwind of emotions when the Catholic family from County Tipperary, Ireland was granted admission. Their arrival came at a time when the Federal Government began to introduce restrictions on immigration. Congress enacted its first comprehensive immigration law on August 3, 1882, just weeks before the Lonergans arrived. This law laid the groundwork for barring the entrance of “undesirables” to America’s soil.

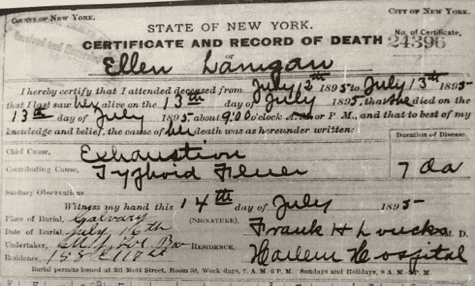

In 1895, twelve years after they entered the U.S., the Lonergan family would experience the tragic death of their daughter, Ellen, who died due to exhaustion after battling typhoid fever for seven days. Her death is a microcosm of the larger reality that surrounded immigrant life in America. Typhoid fever took the lives of so many immigrants because it spread rapidly through contaminated water and uncooked foods. Immigrant tenements were hospitable to disease due to their lack of maintenance, sunlight, running water, and proper sewage. With such awful living conditions came a false association between disease and immigrants themselves rather than the poverty they suffered.

Ellen Lonergan’s Death Certificate, 1895

As immigrants began to enter the streets and tenements of New York City, fear grew at an alarming rate. New faces, new languages, new manifestations of religious belief were linked by longtime residents with the diseases that began to spread like wildfire through the boroughs. The immigrants were scapegoated by nativists as carriers of disease due to their cultural differences. In 1882, the year the Lonergans immigrated to New York, the United States was about to experience a recession as well as an influx of disease. This created a blame game directed at immigrants as innately sick and the cause of the erosion of American life.

The Immigration Acts passed after 1882 reflected fears and hysteria pertaining to new immigrants. In fact, many Americans began to call for more federal legislation to deny immigrants the ability to enter the United States based on their origins. Some believed that barring immigrants from entering the U.S. would decrease the spread of certain diseases. There were countless news articles and pamphlets calling for the federal government to deny entrance of various peoples because of their dangerous lifestyles and unsavory homes.

Such false correlations between immigration and disease led to societal neglect of the most vulnerable, though there were also efforts to improve living standards. In 1867, New York City passed a law to regulate waste and provide bathrooms for tenement inhabitants. Although it was mainly ignored, the Tenement Act of 1867 was a first attempt at regulating living conditions by the Department of Health. Yet, the Annual Report of the Dept. of Health of the City of New York of 1871 disclosed that almost eighty percent of all deaths in New York City were located in tenements. Tragically, the causes of death tended to be diarrheal disease and fever.

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

Thomas Lonergan, my great-great-great-grandfather, bought a grave at Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York after his daughter Ellen passed away. Thomas decided to buy a grave big enough to bury six people but could not afford a tombstone. The only location where he could afford a grave was in front of a “pauper grave” where countless souls were buried without a tombstone, marker, or documentation. Just a few years later, in 1905, his wife Alice would succumb to tuberculosis at the age of 47. Thomas would die alone in a flophouse crushed by alcoholism. Despite their unmarked graves, the Lonergan family was not forgotten. Their determination, their experiences, and their suffering are forever etched in historical memory. There is nothing significant or superhuman about the phenomenon of migration in and of itself. However, the ability to adapt, push through immense pressures, and forgo one’s comfort for the sake of success required Herculean effort.

The fear of a connection between immigration and disease is ever present in our globalized world. The United States and the global community are experiencing unprecedented times in human history where schools, jobs, sports, and even holidays are on pause due to a virologic enemy. The United States and its citizens cannot fall prey to the habits of the past, scapegoating a select few for the human tragedy of contagious diffusion. Perhaps for nations like the United States, it is not a time to discriminate but rather reshape our existence in a way that protects the vulnerable, produces security nets not solely reliant upon capitalistic market systems, and medically protect those infected by disease. Perhaps, we should all emulate the endurance, bravery, steadfastness in the face of heartbreak of immigrants throughout United States history.

The unmarked Lonergan family grave in Calvary Cemetery, Queens, New York, located in between the standing tombstones. The author’s great-great-great grandparents were buried here with their daughter Ellen and other children who did not make it to adulthood.

Sources:

- Gelston, A., & Jones, T. (1977). Typhus Fever: Report of an Epidemic in New York City in 1847. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 136(6), 813-821. www.jstor.org/stable/30107065

- “Immigration Act of 1882.” Immigration to the United States. Howard Bromberg. https://immigrationtounitedstates.org/584-immigration-act-of-1882.html.

- Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “Two women & man in front of outhouses; one woman getting water” New York Public Library Digital Collections. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-4c94-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

- New York City Deaths, 1892-1902; Deaths Reported in July-August-September, 1895; Certificate #: 24396

- New York (N.Y.). Department of Health. (1871). Annual report of the Department of Health of the City of New York … New York City.

- Markel, H., & Stern, A. M. (2002). The foreignness of germs: the persistent association of immigrants and disease in American society. The Milbank quarterly, 80(4), 757–v. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00030

You might also like:

Asian American Immigration: Read More

UT Austin Faculty Train K-12 Teachers in Online

America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019)

Border Land, Border Water: A History of Construction on the U.S.-Mexico Divide by C.J. Alvarez (2019)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.