Our featured author this month, Hanan Hammad, received her PhD in History at UT Austin in 2009. She is now Assistant Professor of History at Texas Christian University and we are proud to introduce you to her excellent new book.

By Hanan Hammad

Millions of Egyptian men, women, and children first experienced industrial work, urban life, and the transition from peasant-based and handcraft cultures to factory organization and hierarchy in the years between the two world wars. Their struggles to live in new places, inhabit new customs, and establish and abide by new urban norms and moral and gender orders underlie the story of the making of modern urban life—a story that has not been previously told from the perspective of Egypt’s working class.

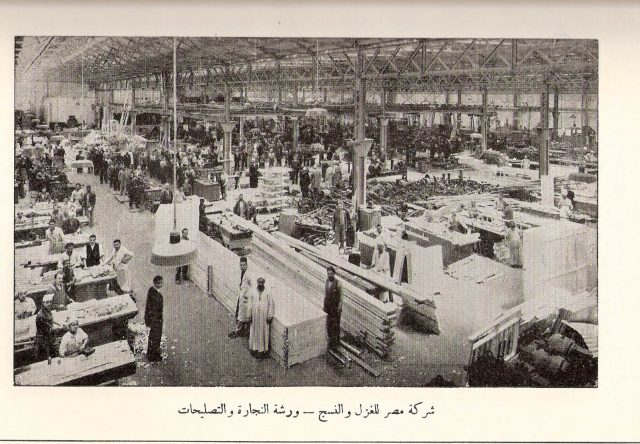

Reconstructing the ordinary urban experiences of workers in al-Mahalla al-Kubra, home of the largest and most successful Egyptian textile factory, demonstrates how the industrial urbanization of Egypt transformed masculine and feminine identities, sexualities, and public morality. Coercive industrial organization and hierarchy concentrated thousands of men, women, and children at work and at home under the authority of unfamiliar men, intensifying sexual harassment, child molestation, prostitution, and public exposure of private heterosexual and homosexual relationships. Juxtaposing these social experiences of daily life with national modernist discourses shows us that ordinary industrial workers, handloom weavers, street vendors, lower-class landladies, and prostitutes—no less than the middle and upper classes—played a key role in shaping the Egyptian experience of modernity.

Factory culture and organization were sites where male workers and supervisors negotiated traditional and modern masculinity. Men often used violence and aggression on the shop floor as expressions and performances of the contestation, ambivalence, and changing of men’s fluid masculine identities. Men negotiated the coercive, industrial hierarchy by oscillating between docility and violence. In an attempt to strike a balance between personal pride in making a livelihood and protecting their own integrity, workers evaded authority and developed male associations and bonded among themselves.

Outside factories, workers coming from rural areas had to partake in urban traditions and manners, despite mutual hostility with townspeople. Violence broke out as a result of the division between the urbanites and the factory workers. In that context masculine gender identity, the performance of masculinity, and the construction of manhood were important elements in adapting to industrial urban life. In their competing and fluid loyalties, working-class men developed their notion of the ideal masculine identity and created social locations for peer bonding and friendship.

Textile factories opened more opportunities for rural women to venture into urban life and to assume an industrial working-class identity. Female industrial workers in both handloom and mechanized factories went through a multifaceted process of proletarianization while being subjugated to the coercive industrial hierarchy and facing both capitalism and patriarchy inside and outside the factory. Factory work subjected women to sexual harassment and social stigma. They acquired skills to operate modern machinery, rose in the social ranks of the salaried urban population, and gained experiences in dealing with a factory system. Yet they had the lowest status and payment among the workers in the male-dominated industrial hierarchy and their morality became subject to communal suspicion and mistrust.

Taking advantage of unprecedented growth in the demands for cheap accommodation, women of the popular classes invested in workers’ lodging and set up their own businesses to provide workers food, drink, and other cheap commodities and services. Entrepreneurial women contributed immensely to shaping the socioeconomic transformation and labor history. These new patterns of economic investment and work allowed lower-class women to assume powerful positions in their households and enabled them to challenge patriarchal norms. These lower-class landladies played an important role in shaping new workers’ experiences with urban life, undermined the agricultural economy in favor of real-estate investment, and challenged the power of the state in the spheres of urbanization and urban control.

With the lack of privacy and increasing sociocultural differences among individuals sharing limited spaces, sexual life became vulnerable to public exposure, and exposing sexuality was a way to negotiate disputes in one’s own favor. Children and adults from different geographical origins often shared living and sleeping spaces. Unmarried female and male strangers shared houses with urbanite families and individuals. In living and work environments marked by anxiety, jealousy, mistrust, and suspicion, it was not unusual for ordinary disputes with neighbors, roommates, housemates, and coworkers to slip into judging one another’s sexual behaviors. By examining the social arguments and controversies over sexual practices, such as women’s harassment, child molestation, sodomy, sex outside wedlock, and homosexuality, people in this transformative urban milieu constructed fluid and intricate, rather than rigid, social norms of licit and illicit sexuality.

The largest labor strike in the history of modern Egypt took place in 1947. Striking workers exposed horrific work and living conditions and shattered the idealistic, nationalist image of industry as a banner of nationalism and economic independence. Prostitution was blamed for the deterioration of workers’ health, which exposed all workers’ sex lives to public scrutiny. Religious and nationalist discourses against sex work that had been a part of the urban landscape made the morality and sexuality of the working classes a target of bourgeois anxiety. Invoking morality against sex workers resonated with the nationalism and the state’s effort to medicalize, control, and stigmatize the lower class’s sexuality, but these discourses also served to overlook tuberculosis, malnutrition, and other diseases that preyed on the poor urban population and triggered strikes and urban unrest.

Industrial Sexuality: Gender, Urbanization, and Social Transformation in Egypt, The University of Texas Press (2016)

Further reading on the history of gender, sexuality and the working classes in Egypt:

Liat Kozma, Policing Egyptian Women: Sex, Law, and Medicine in Khedival Egypt (2011)

In Policing Egyptian Women, Liat Kozma traces the effects of nineteenth-century developments such as the expansion of cities, the abolition of the slave trade, the formation of a new legal system, and the development of a new forensic medical expertise on women who lived at the margins of society. Kozma outlines the complicated manner in which the modern state in Egypt monitored, controlled, and “policed” the bodies of subaltern women. Some of these women were runaway slaves, others were deflowered outside of marriage, and still others were prostitutes.

Joel Beinin, Workers and Peasants in the Modern Middle East (2001)

Inspired by the Indian Subaltern Studies school, this social history offers a survey of subaltern history in the Middle East. Beinin illuminates how their lives, experiences, and culture can inform our historical understanding. Beginning in the eighteenth century, the book charts the history of the peasants and the modern working classes across the lands of the Ottoman Empire and its Muslim-majority successor-states.

Judith E. Tucker, Women in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (1985)

Focusing on lower-class women, this study traces changes in the work role and family life of peasant women in the countryside and craftswomen and traders in Cairo during the rapid social and economic change in the nineteenth century. Brought about by the country’s developing ties with the European economy, the effects of capitalist transformation on women are studied in detail, using material from the Islamic court records.

Beth Baron, Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics (2007)

Focusing on Egyptian national and gender politics between the two world wars, Baron shows how vital women were to mobilizing opposition to British authority and modernizing Egypt. Egypt as a Woman explores the paradox of women’s exclusion from political rights at the very moment when visual and metaphorical representations of Egypt as a woman were becoming widespread and real women activists–both secularist and Islamist–were participating more actively in public life than ever before.

Films on gender, sexuality and the working classes in Egypt:

I’m suggesting few Egyptian films, mostly from the social realism genre, that discuss issues of gender and sexuality in the intersection with class, social morality, urbanism and rural exploitation.

Youssuf Chahine, Cairo Station, 1958

In the hustle and bustle of Cairo Station, this movie tells a story of romantic infatuation, frustrated sexual desires, and labor struggles in the newly-independent Egypt. A physically-challenged peddler coming from Upper Egypt falls for a gorgeous lemonade seller who is engaged to one of the station’s workers. That fiancé is a strong and respected porter struggling to unionize his fellow workers to combat their boss’ exploitative and abusive treatment.

Muhammad Khan, Factory Girl, 2013

Through the ordinary life of a 21-year-old female worker in a Cairo textile factory, the movie engages with class aspiration, female desires, and moral hypocrisy. When the impoverished factory girl becomes attracted to the factory’s new supervisor, she discovers the glass ceiling of class and gender hierarchy inside the factory and the moral hypocrisy of the larger society that divides the urban working and middle classes.

Henry Barakat, al-Haram (Sin), 1965

This masterpiece portrays the cruel reality of itinerant rural workers. The newspaper Le Monde wrote: “we have been attracted to this movie due to the true picture that reflects the suffering of this village, the picture is not about a problem for one individual; it’s about the reflection of everything surrounding her, from people to culture.”