By Jacqueline Jones

On March 21, 1861, Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederate States of America, delivered an extemporaneous speech to an enthusiastic crowd in Savannah, Georgia. Stephens declared that new nation had been created in order to refute the idea enshrined in the Declaration of Independence that “All men are created equal.” According to Stephens, “Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and moral condition.” Four years later the Confederacy lay in ruins, and nearly 700,000 Americans lay dead. Three and a half million black Southerners were celebrating their release from bondage. Intending to preserve the institution of slavery, secessionists had started a war that destroyed the very way of life they had set out to defend.

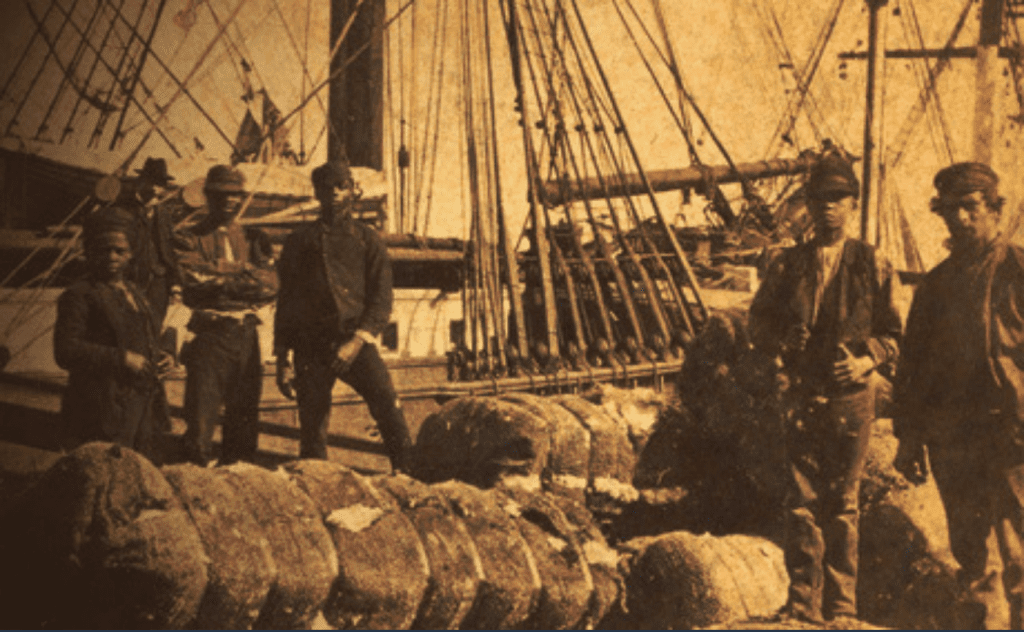

Saving Savannah chronicles the wholly unanticipated consequences of the Civil War for Confederate slaveholders and the dramatic efforts of the city’s black people to live life on their own terms. In 1860 Savannah was a lively river port of 22,000 (people of color made up 40 percent of the population), processing and shipping rice, cotton, and lumber to the North and to Europe. Visitors enjoyed the balmy winters and marveled at the city’s charming, leafy squares and its elegant brick and pink-stucco mansions. Frequent, elaborate parades and processions displayed a social order based on the power of whites over blacks, rich over poor, men over women, native-born over immigrant. City fathers tried to enforce white/black, free/slave divisions, but often failed. A small number of wealthy merchants, lawyers, and bankers managed to convince a large number of white dockworkers (many of them Irish immigrants) that the Democratic Party represented the interests of all white men regardless of class or ethnic background. At the same time, the city’s commercial economy also depended on the labor of black men, enslaved and freed, who hauled staples from the railroad depot to the processing mill and then to the wharves. The fact of the matter was that black and poor-white workers shared lowly material conditions. Together, black and white men and women of the laboring classes ate, slept, drank, danced, and fought with each other in the “disorderly” parts of town and together they ran an underground economy fueled by resourceful men and women who trafficked in goods stolen from their social betters.

The black community was remarkably well-organized. Black education was illegal; but each morning some enslaved children hurried through the streets, their primers wrapped in paper and tucked away in lunch pails, on their way to schools operated secretly by black teachers. Men and women belonged to mutual-aid and burial associations, secret societies in the West African tradition. Moreover, the community openly supported their own churches where ministers preached a subversive message to their congregants each Sunday. Invoking a creed of universal Christian brotherhood, the Reverend Andrew Marshall, pastor of First African Baptist Church, demanded to know, “How many of those to whom we are subject in the flesh have recognized our common Master in Heaven, and they are our masters no longer?” Savannah whites were convinced that their systems of social control would keep all blacks, enslaved and free, in their “place”; but they were wrong.

The onset of military hostilities in April 1861 caused an immediate disruption to Savannah’s prosperity and its pretenses of a well-ordered hierarchy. Trade came to an abrupt halt, and many white workers lost their jobs. Irish immigrants who had come south from New York for the busy season (November to May) packed up and went home. An influx of Confederate soldiers—up to 9,000 at one point—overtaxed the city’s natural and law-enforcement resources. Soldiers of modest backgrounds deployed up and down the Georgia coast endured sweltering summers, tormented by mosquitoes and sandflies. They resented the officers who brought their personal cooks and valets to camp and returned to Savannah periodically to take a hot bath or attend a party. Laboring men were less than enthusiastic conscripts into the Confederate army. By early 1863 the local papers were running advertisements for army deserters—listing their age, height, and distinguishing physical characteristics– where ads for fugitive slaves had been posted before the war. The antebellum class consensus among the city’s elites faltered, as even well-off Jews became the targets of anti-Semitic attacks. Even the wealthiest Savannahians were not immune to wartime dislocations: the Chicago-born Nelly Kinzie Gordon, married to a scion of one of Savannah’s most distinguished families, endured the scorn of her neighbors when they learned that several of her kinsmen, including her uncle General David Hunter, were serving in the Union army and stationed in coastal waters not far from the city. In the spring of 1864, poor white women staged a downtown bread riot; their anger and frustration highlighted the sufferings of many in the city scrounging for work—and for food.

Meanwhile, black people emerged as a subversive force within the heart of the Confederacy. Some men served as pilots, scouts and spies for Union forces, helping gunboats to navigate through the intricate lattice-work of coastal waterways. Other men, beginning in 1862, joined the Union army and navy. Some Savannah blacks fled to Federal lines, while others remained behind and made money supplying Confederate army camps. One butcher, Jackson Sheftall, profited handsomely, and in 1862 paid $2600 to free his wife Elizabeth. Labor-hungry Confederate officials charged with constructing fortifications soon found that they needed to pay cash wages to men and women of color regardless of whether they were slaves or free. Cooks and domestics worked slowly and grudgingly, if at all. Church members defied city authorities and sang praise-hymns to freedom. The institution of slavery was crumbling at lightning speed and black people themselves were hastening its demise.

Although the Confederacy died in April, 1865, the Confederate project premised on white supremacy did not. In late 1864 Union General William Tecumseh Sherman spared the city from destruction, and in an effort to restore public “order,” he even allowed the mayor and members of the city council to remain in office. Over the next few years, Union military officials, federal Freedmen’s Bureau agents, and representatives of northern missionary associations would join with white politicians, police, and employers to stall black people’s struggles for autonomy and self-determination. Most whites, whether northern or southern, believed that black people were not really working unless they worked under the supervision of a white person, in the fields or in a kitchen. These whites frowned upon freed men and women who attempted to run their own schools and farm their own land, separate from their former masters and mistresses.

After the war, black leaders emerged to offer diverse—and at times conflicting—strategies for political empowerment. Particularly outspoken individuals included James Simms, carpenter, preacher, labor organizer, and principled integrationist determined to win for blacks full citizenship rights; and Aaron A. Bradley, a militant lawyer and professional provocateur bent on championing the interests of black laborers in the cotton and rice fields. Tunis G. Campbell and Ulysses L. Houston favored self-sufficient black colonies as the way toward collective autonomy. The Reverend Garrison Frazier stressed the significance of landownership, but he also counseled accommodation to the white powers-that-be. Richard W. White, a Union army veteran inclined toward poetry, confounded whites because he looked white; he was the subject of an 1869 court case where his “race” was in dispute. City officials were trying to prevent all black men from running for office; in order to reestablish the antebellum order, they needed first to identify who was “white” and who was “black.” Yet ironically these “racial” distinctions did not always depend on the color of a person’s skin. With the exception of Frazier, all of these men occupied public office briefly, until local whites celebrated the departure of Union occupation forces by suppressing and eventually eliminating the black vote via a poll tax and election-day violence. By the early 1870s, in Savannah and along the Georgia coast, few freedmen were allowed to vote and none served on juries, the city council, or the police force. The outlines of the Confederate project would survive for the next hundred years.

Jacqueline Jones, Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War

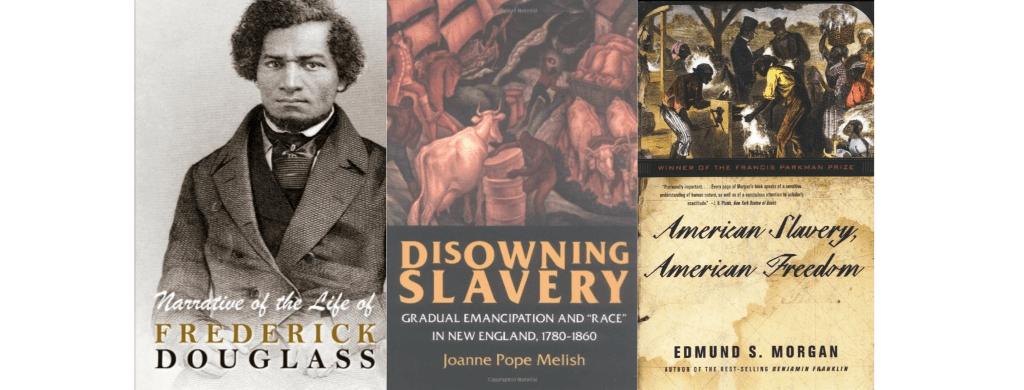

Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia, (1975).

Morgan’s book seeks to account for two related historical developments: The origins of American slavery, and the fact that many of the leading Founding Fathers–—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, James Madison, and James Monroe, to name but a few—owned enslaved workers. Seventeenth-century Virginia landowners cobbled together plantation labor forces from an unruly mix of Europeans, Native Americans, and people of African descent. Most field workers were young English indentured servants, bound to a master for a stipulated number of years. Homesick and forced to perform new and arduous forms of work—cutting down trees to clear forests, and then toiling stooped over in tobacco fields—these servants proved to be resentful members of plantation households. Within the first half-century of Virginia’s founding, a few white men with political connections owned most of the fertile lands in the eastern part of the colony. Once freed, former servants found themselves without money, land, or hope. Armed, they formed a dangerous element in the colony, and in 1676 launched a bloody challenge to the authority of elites, in the form of an uprising called Bacon’s Rebellion. Seeking to curb young white men’s violence, elites began to shift their workforces away from white indentured servants and toward enslaved peoples of African descent. Henceforth, even impoverished white men could become part of the large body politic, separate and distinct from the mass of black workers denied fundamental civil and human rights. Morgan frames this narrative as a study in the history of poverty. The founders of Virginia, and the founders of the United States, were sensitive to contemporary conditions in England, where many workers remained chronically underemployed and resorted to theft and other forms of property crimes in order to survive. Under the system of American slavery, colonial elites believed that they had solved the problem of the poor as a dangerous, unproductive element in society. All white men could enjoy a measure of political equality, while all enslaved workers remained outside the bounds of civil society. Therefore, according to Morgan, it was no coincidence that many of the Founding Fathers owned slaves. A republican form of government worked best, they believed, if the dispossessed were excluded from it. In Morgan’s words, “Aristocrats could more safely preach equality in a slave society than in a free one.” Morgan’s ground-breaking work reminds us that, when deployed by powerful people, racial ideologies constitute political strategies of immense force. Whenever my students encounter the word “race” in an historical text, I ask them to consider who benefits from these ideas. How are these ideas manifested in everyday life, and especially in patterns of work? American Slavery, American Freedom reveals that the institution of slavery was not a foregone conclusion, but the result of a series of conscious political decisions that would shape the nation for centuries to come.

Joanne Pope Melish, Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and ‘Race’ in New England, 1780-1860, (1998).

In Disowning Slavery, Melish explodes the myth that slavery in the North was a relatively benevolent system. In New England, early anti-slavery pronouncements stemmed less from enlightened humanitarianism than from fears that descendants of Africans had no place in tight-knit villages of English religious believers. In this view, the ideal citizen was a white man, a “freeman” who could perform several roles simultaneously—head of a household, father and husband; church congregant; landowner, and member of the local militia. The few enslaved blacks in the region were barred from owning land and serving in the militia; thus they represented perpetual outsiders in self-proclaimed “Godly” communities. After the Revolution, the northern states began to emancipate their slaves, but several of those states passed laws that guaranteed freedom only for the children of current slaves. Even as free people, blacks in New England remained the target of discrimination. Many lacked the means or opportunity to buy land or pursue a trade. They were, in the words of Frederick Douglass, “slaves of the community” – barred from voting, serving on juries, sending their children to public schools, and even in some cases from moving around in search of jobs. Many whites thus perceived blacks as a group of historically and perpetually poor people. Black leaders’ eloquent calls for full freedom alarmed whites, who responded with new racial ideologies. For example, many whites argued that black people were by nature dependent on charity; but some of these whites also held that black people aggressively sought out good jobs at good wages, in the process denying white workers of their privileges. Melish reminds us that racial ideologies need not be logical or consistent in order to shape a society, or a dominant group’s view of itself. The vicious anti-black riots that engulfed several northern cities in the 1820s and 1830s showed that devastating racial ideologies were not a regional phenomenon limited to the South, but rather a national phenomenon with southern and northern variations.

Frederick Douglass, Narrative, (1845).

By any measure, Douglass’s Narrative is an extraordinary document—as autobiography, anti-slavery polemic, literature, and primary text illuminating mid-nineteenth-century American life. Douglass was born a slave on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1818, the son of a white father and an enslaved woman. One of the most moving parts of his story revolves around his learning to read and write. Literacy opened a whole new world to him, but also embittered him, as he contemplated the injustice of slavery. In 1838 he forged his name on a pass, disguised himself as a sailor, and escaped to Massachusetts. By the 1840s he was travelling throughout the North and Great Britain, electrifying audiences with his eloquence and his compelling story of escape from bondage. I teach the Narrative in my Signature course (a seminar offered to first-year students) called “Classics in American Autobiography.” The students appreciate this text on many different levels, and eagerly engage in the discussion of a central question: How does one make a case for freedom in a time and place where many people assume slavery is a “natural” condition for a certain group of people? Douglass crafted his Narrative to make the case against slavery in terms Northerners would understand. He focused not on a call for universal human rights—an argument that resonates with us today—but on the brutality of slavery and its effects on the family. Just a few pages into the Narrative he gives a graphic description of the whipping of his Aunt Hester by her lascivious owner; stripped naked and tied with her hands above her head, she endured a beating so vicious that her “warm, red blood (amid heart-rending shrieks from her, and horrid oaths from him) came dripping to the floor.” In order to counter the stereotype that enslaved workers were child-like and dependent, Douglass describes the “manly” confidence and pride instilled in him after winning a fistfight with an overseer. The passage where Douglass tells of his experience as a young slave, standing on a bluff overlooking the Chesapeake Bay and wistfully watching the white-sailed ships moving swiftly through the water, is one of the most beautiful in all of American literature.