Like countless other cultures and countries throughout the world, the United States has its own creation myth—its own unique, dramatic story intended to explain where we came from and who we are today. In the case of the United States, this story holds that the nation was conceived in “racial” differences, and that over the last four centuries these self-evident differences have suffused our national character and shaped our national destiny. The American creation story begins with a violent, self-inflicted wound, and features subsequent incremental episodes of healing, culminating in a redemption of sorts. It is, ultimately, a triumphant narrative, one that testifies to the innate strength and moral rectitude of the American system, however imperfect its origins.

According to this myth, the first Europeans who laid eyes on Africans were struck foremost by their physical appearance—the color of their skin and the texture of their hair—and concluded that these beings constituted a lower order of humans, an inferior race destined for enslavement. During the American Revolution, Patriots spoke eloquently of liberty and equality, and though their lofty rhetoric went unfulfilled, they inadvertently challenged basic forms of racial categorization. And so white Northerners, deriving inspiration from the Revolution, emancipated their own slaves and ushered in a society free of the moral stain of race-based bondage.

The Civil War destroyed the system of slavery nationwide, but new theories of scientific racism gave rise to new forms of racial oppression in the North and South. Not until the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 did the federal government dismantle state-sponsored race-based segregation and thus pave the way for better race relations. Though hardly an unmitigated triumph, the election of Barack Obama as president in 2008 signaled the dawn of a post-racial society, and offered a measure of the distance the country had travelled since slavery prevailed in British North America.

Yet America’s creation myth is just that—a myth, one that itself rests entirely on a spurious concept: For “race” itself is a fiction, one that has no basis in biology or any longstanding, consistent usage in human culture. As employed in the popular rendition of America’s national origins, the word and its various iterations mask complex historical processes that have little or nothing to do with the physical make-up of the people who controlled or suffered from those processes.

Like its worldwide counterparts, the American creation myth is the product of collective imagination, not historical fact, and it exists outside the realm of rational thought. Americans who would scoff at the notion that meaningful social or temperamental differences distinguish brown-eyed people from blue-eyed people nevertheless utter the term “race” with a casual thoughtlessness; consequently the word itself helps to sustain not only the creation myth but also all the human misery that the myth has wrought over the centuries. In effect, the word race perpetuates—and legitimizes—the notion that some kind of inexorable primal prejudice has driven history, and that, to some degree at least, the United States has always been held hostage to “racial” differences.

Certainly the bitter legacies of historic injustices endure in concrete, blatant form. Today certain groups of people are impoverished, exploited in the workplace, or incarcerated in large numbers in prison. This is the case not because of their “race,” however, but rather because at a particular point in U. S. history certain other groups began to invoke the myth of race in a bid for political and economic power. This myth has served as a tool that one group can use to ratchet itself into a position of greater advantage in society, and a justification for the economic inequality and the imbalance in rights and privileges that result.

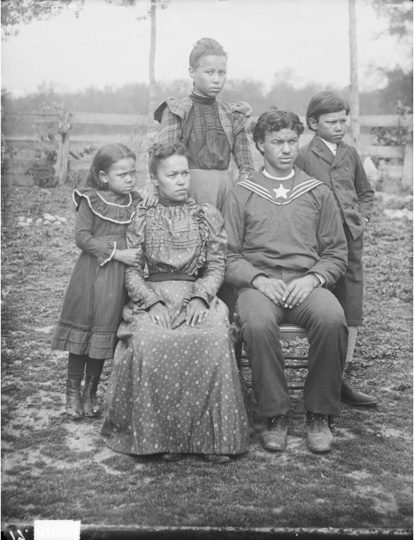

My book is about the way that the idea of race has been used and abused in American history. It focuses on the contradictory and inconsistent fictions of “race” that various groups of people contrived for specific political purposes throughout American history. As deployed by the powerful, race serves as a rationale for brutality, and its history is ultimately a local one, best understood through the lives of individual men, women, and children. The stories I examine in the book range over time and space to consider particular, shifting processes of racial myth-making in American history: in mid-seventeenth-century Maryland; Revolutionary-era South Carolina; early-nineteenth-century Providence, Rhode Island; post-Civil War Savannah, Georgia; segregationist Mississippi; and industrial and post-industrial Detroit.

This book is about physical force flowing from the law, the barrel of a gun, or the fury of a mob; but it is also about the struggle for justice and personal dignity waged by people of African descent in America. Their fight for human rights in turn intensified policies and prejudices based on so-called “racial” difference. In fact, in the region that would become the United States, race initially developed as an afterthought or a reaction—an afterthought, because for several generations the exploitation of people of African heritage required no explanation, no justification beyond the raw power wielded by the captors; and a reaction, because a concerted project based on the myth of race eventually arose in response to individuals and groups such as abolitionists and civil-rights activists who challenged forms of state-sanctioned violence and legal subordination that afflicted enslaved people and their descendants.

For the first century and a half or so of the British North American colonies, the fiction of race played little part in the origins and development of slavery; instead, that institution was the product of the unique vulnerability of Africans within a roiling Atlantic world of empire-building and profit-seeking. Not until the American Revolution did self-identified “white” elites perceive the need to concoct ideas of racial difference; these elites understood that the exclusion of a whole group of native-born men from the body politic demanded an explanation, a rationalization. Even then, many southern slaveholders, lording over forced-labor camps, believed they needed to justify their actions to no one; only over time did they begin to refer to their bound workforces in racial terms. Meanwhile, in the early nineteenth-century North, race emerged as a partisan political weapon, its rhetorical contours strikingly contradictory but its legal dimensions nevertheless explicit. Discriminatory laws and mob actions promoted and enforced the insidious notion that people could be assigned to a particular racial group and thereby considered “inferior” to whites and unworthy of basic human rights. Black immiseration was part and parcel with white privilege, all in the name of—the myth of—“race.”

By the late twentieth century, transformations in the American political economy had solidified the historic liabilities of black men and women, now in the form of segregated neighborhoods and a particular social division of labor within a so-called “color-blind” nation. The election of the nation’s first black president in 2008 produced an out-pouring of self-congratulation among Americans who heralded the dawn of a “post-racial” society. In fact, the recession that began that year showed that, although explicit ideas of black inferiority had receded (though not entirely disappeared) from American public discourse, African Americans continued to suffer the disastrous consequences spawned by those ideas, as evidenced by high rates of poverty, unemployment, and home foreclosures.

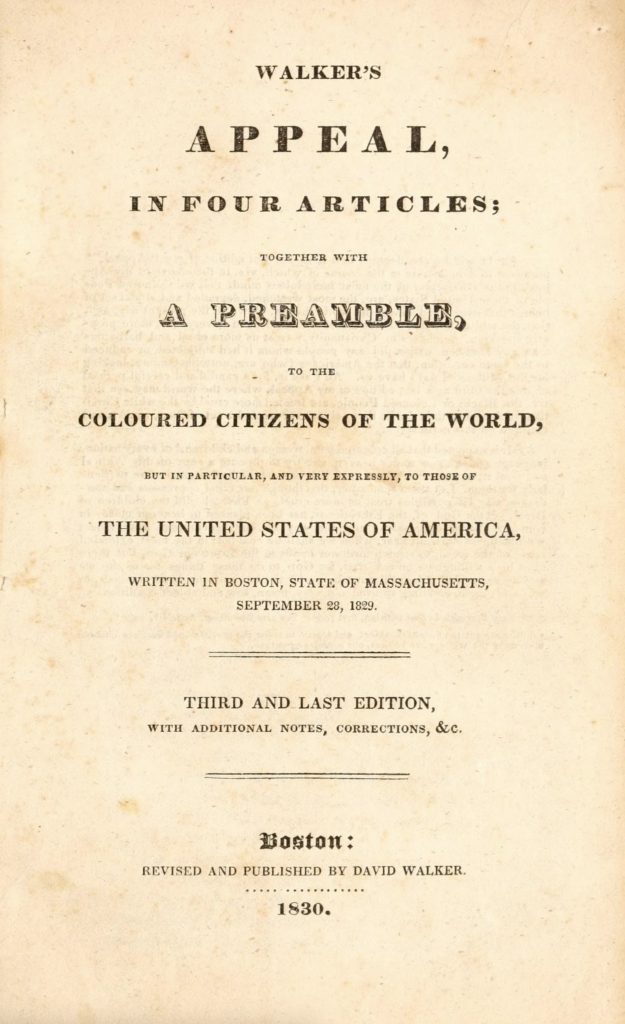

This book takes its title from a recurring phrase used by David Walker in his brilliant, militant polemic, Walker’s Appeal, first published in 1829. Walker, a native of North Carolina, had been born to a free mother and an enslaved father. By the 1820s he was living in Boston and playing a leading role in the fight against slavery. His Appeal draws from history, political theory, and Christian theology to expose the falsity of race. Walker argued that Europeans had devised a uniquely harsh system of New World slavery for the sole purpose of forcing blacks to “dig their mines and work their farms; and thus go on enriching them, from one generation to another with our blood and our tears!!!!” Gradually white people, he wrote, concocted lies by which they “dreadfully deceived” themselves, ruses to keep blacks in ignorance and subjection—the idea that blacks “are an inferior and distinctive race of beings.” Prescient, he warned of a coming conflagration that would destroy the system of slavery; but, like other abolitionists of the time, he failed to anticipate that, although slavery would die, “race” would survive and mutate into new and hideous shapes.

In the early twenty-first century, the words “race,” “racism,” and “race relations” are widely used as shorthand for specific historical legacies that have nothing to do with biological determinism and everything to do with power relations. Racial mythologies are best understood as a pretext for political and economic opportunism both wide-ranging and specific to a particular time and place. If this explication of the American creation myth leads to one overriding conclusion, it is the power of the word “race” to distort our understanding of the past and the present—and our hopes for a more just future—in equal measure.

Jacqueline Jones, A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama’s America