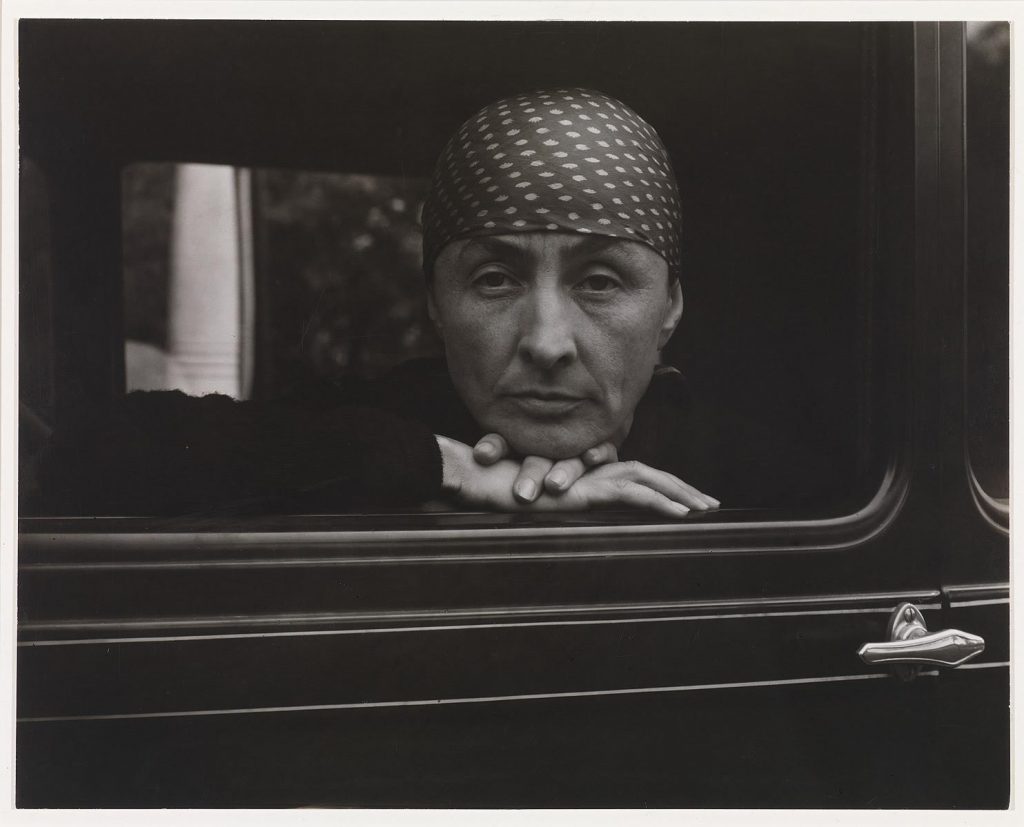

I remember Georgia O’Keeffe. I couldn’t have been but three, first time I met her. She was already an older woman by then, or late middle age, at least. She was tall and perfectly centered, with a slender frame and grey hair pulled back in a tight bun. She wore long sleeves and dark jeans. She smoked only the best Cuban cigars. Women weren’t supposed to smoke cigars at all. But she got away with it. She and Frida Kahlo.

Miss O’Keeffe got her smokes from La Habana. They were already hard to get in ’61. The trade embargo was not yet in place, but things were already getting sticky with Fidel. The State Department didn’t like the combat fatigues, and the mob wanted their casinos back. I think they drove Fidel into Soviet arms. After that, Ché Guevara went to Angola, with a habanero in his teeth, just like Miss O’Keeffe. Cuban cigars became contraband. Reserved for drug traffickers and CIA agents. I suspect Miss O’Keeffe had some stashed away for a rainy day. But in the summertime, it rained every afternoon on the high plains of New Mexico. You learned to bide your time. You knew that’s just the way it was going to be.

Back then, people might have said that Georgia O’Keeffe dressed like a man, if she weren’t so strikingly feminine. Sometimes, she switched the jeans for a long dark skirt, the sort Jean Harlow might have worn in a Western. Her perfume was something classic from the 1920s, sprayed on with granny’s atomizer, a little pungent, perhaps, but a good combination with the juniper and piñon all around us. We would meet her often at the Piggly Wiggly in Santa Fe.

She drove her pickup truck down from Ghost Ranch to Santa Fe about once a week for provisions. Ghost Ranch was her home in Abiquiu, north of Española. We rode in with Mom from Tesuque. In a 1960 turquoise Volkswagen. It wasn’t that we would just see her and comment that there goes a famous person. She would always speak, and she remembered our names, and we would remember her. I even remember a plane ride to Midland, sitting in the same row with Miss O’Keeffe. To go to Houston, back then, you flew from Santa Fe to Midland and there, you took the train. I don’t know where Miss O’Keeffe was going. Probably, New York. She had to check in with the art world once in a while.

One day, Daddy had to drive out to Abiquiu to fix Miss O’Keeffe’s hi-fi. Stereo was still a dream of the future. Daddy was good at fixing hi-fi systems. And the old hi-fis were very good machines, but they needed attention. You had to change the needle often, and when a vacuum tube burned out, you had to identify which one it was, buy the right replacement, and change it without electrocuting yourself.

Daddy was down on the floor, on his back, underneath Miss O’Keeffe’s hi-fi, and her German Shepherd walked into the room, growling, hackles raised. Miss O’Keeffe was right behind him. Don’t move, she said, softly. Instructions for the man on the floor, not for the dog.

She managed to call off her dog. Daddy got it. We had German Shepherds, too. Far better than locks on the door for looking after yourself, or your wife and kids. In what was left of the wild, wild west. Aware of prowlers and mountain lions.

I suspect Sanders and Associates had sold Miss O’Keeffe her hi-fi, and that was why Daddy would drive out there to fix it. He worked for them. It was about an hour away. Maybe it was just because he was a nice guy. She didn’t let many people into her sanctuary. Her dog knew that.

We often wondered, years later, what her music was. Big bands or Aaron Copeland; maybe Stravinsky. But Daddy’s gone now, and we never got around to asking him.

Igor Stravinsky came to Tesuque in ’61. He was an elderly man, by then. He came to direct his masterpiece at the Santa Fe Opera House. It was three blocks from where we lived, so Mom and Daddy went. They were young marrieds with three babies, no money and season tickets to the opera. Where will you ever see that again? Miss O’Keeffe was there, of course.

After that, Daddy bought a recording of the Rite of Spring to play for us at home on our hi-fi. We just called it, the jungle record. We played it over and over. We hid behind the couch for the loud and rowdy parts. Alongside that, the record changer dropped Toscanini’s Beethoven, Harry Belafonte’s Calypso and the complete The Kingston Trio. It was all music to us.

Daddy worked for Sanders and Associates, a King Ranch subsidiary, which meant Alfred King was trying his hand at import-export in Santa Fe. It folded because Mr. Sanders was cooking the books. Daddy turned him in to Mr. King, and then we moved to Dallas. We watched Kennedy get shot while we were there. Dealey Plaza was just a few blocks away. Shit goes down that way in Texas. JFK didn’t have a German Shepherd. He sure needed one.

But this was supposed to be about Miss O’Keeffe. She was lovely. She had climbed the steep rock wall alone to get to the place where she was. Her masculine dress, her artistic style, and her cigars were a testament to her eternal readiness for the ongoing struggle. She possessed the peace that had cost her everything she had. She had walked through the fire.

Miss O’Keeffe gave up painting as a young woman, after attending the Chicago Art Institute’s school for starving artists. Said the smell of turpentine made her puke. For a while, she drew for an advertising firm in Chicago, then she taught public school in Amarillo. While she was in Amarillo, she started walking in the Palo Duro Canyon. It seduced her heart back to beauty.

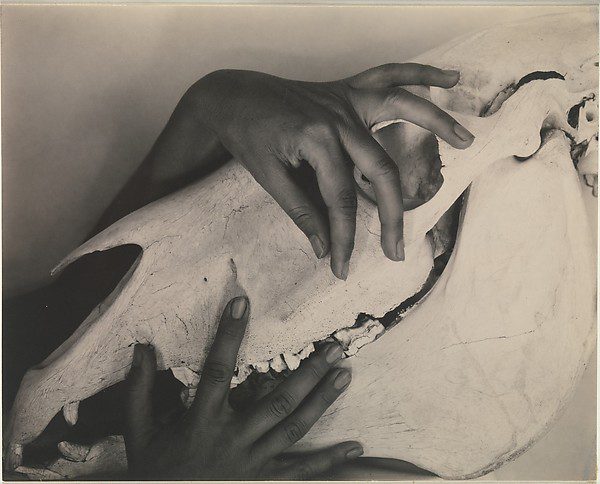

She contracted the Spanish Flu in 1918, along with 200 million others worldwide, but she survived. She married Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer from New York, and he made many portraits of her. But she couldn’t bear his snobby family, or his philandering, so she escaped to New Mexico every summer. Hiking up high. It was there that she started painting again.

When Stieglitz died in 1946, she settled permanently at Ghost Ranch. She drove an old Model A until the wheels fell off. Then she got a Ford pickup, the one I remember from the supermarket in Santa Fe.

Ghost Ranch was out near Los Alamos, where the atomic bomb was in the process of becoming a world-changing reality. Los Alamos is the strangest city on the planet. Complex, yet simple. If you drive into town to buy supplies, someone follows you. That is why Miss O’Keeffe preferred the supermarket in Santa Fe. She was recognized in Los Alamos and not welcome, there. She was recognized in Santa Fe and loved.

Her life was an ongoing thermonuclear moment. Once, the soil rebelled and burned her workshop to the ground. Unable to finish a commissioned piece in New York, she had a nervous breakdown and spent two years in a psychiatric hospital. Behind bars with all the other artistic souls. Big Nurse, medication and electro-shock. She emerged, changed, but unscathed. She strode out of there with frightful courage, strong legs and unyielding decision.

That was 1932. The year that changed everything for her. From then on, she was determined, committed and, yes, maybe even, happy. More and more, she spent her time in the land that gave her life. She was more alone, but not lonely. She went back to New York to bury Stieglitz in 1946. After that, her only love was the the New Mexico desert. She painted it, smoked Cuban cigars, and watched the sun set, over and over again.

She died in 1984. She was 98 years old. She was not painting anymore. She would sit and watch the red desert cliffs on the high plane as the sun rose and set each day. Taking care of the beauty around her, just watching, perennially caught up in its angel fire.

Also by Nathan Stone on Not Even Past:

The Tiger

The Battle of Chile

Rodolfo Valentín González Pérez: An Unusual Disappearance

You may also like:

Dagmar Lieblova, Survivor by Dennis Darling

Digital Teaching: Mapping Networks Across Avant-Garde Magazines by Meghan Forbes

Policing Art in Early Soviet Russia by Rebecca Johnston