By Horus T’an

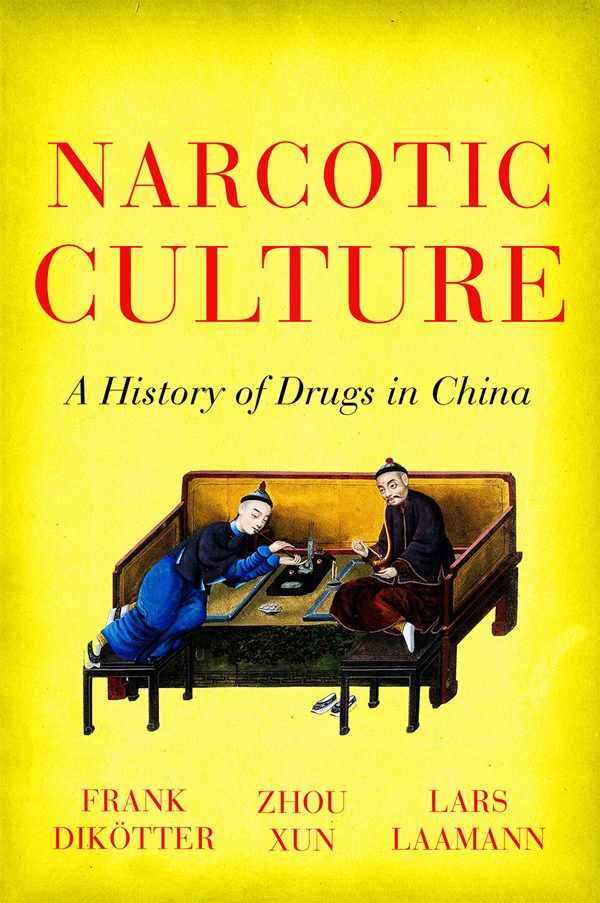

The opium myth is one of the most important pillars of the conventional narrative of modern Chinese history. According to the myth, opium is presumed to be a highly addictive narcotic and highly harmful to its users’ health, and Great Britain used its military superiority to impost the shameful opium trade on China and turn it into a nation of opium addicts who were “smoking themselves to death while their civilization descended into chaos.” In the opium myth, opium symbolizes the imperialists’ pernicious intention to dominate China and the tragedies suffered by all the nations facing imperialist aggression. In Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China, Frank Dikötter, Lars Laamann, and Zhou Xun debunk the opium myth through exploration of the history of opium in China from the sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. They point out that the opium myth was invented by nationalist reformers and never reflected the reality of opium in Chinese society during the late imperial period. The authors also argue that the miseries experienced by Chinese opium smokers from the end of the nineteenth century were brought on by the anti-opium campaigns launched by the Chinese authorities rather than the chemical property of opium. These campaigns degraded the opium smokers into a morally depraved status and forced them to use more harmful semi-synthetic opiates like morphine and heroin.

The opium myth analyzed opium smoking practices in China and India in isolation from the cultural and social factors sustaining these practices. In contrast, this book shows that opium in China served as an essential lubricant in male social activities. Opium was prepared and appreciated in highly sophisticated ceremonies by male social elites. Opium also served as a panacea for many ailments. Quite contrary to the incurable addicts in the opium myth, the authors argue that the opium consumed in both China and India was relatively moderate and had few harmful effects on either health or longevity. Most opium smokers were able to control the quantity of the opium they consumed, and the irresistible compulsion toward ever-increasing doses was not a common phenomenon among them.

The highlight of this discussion about the history of opium before the end of the nineteenth century is the comparison between tobacco and opium. The authors demonstrate that tobacco and opium played a relatively similar role in social activities and people showed similar attitudes toward them. There were alarms in the 1830s and 1840s from a few Han officials over moral decay and the breakdown in social order caused by the prevalence of opium. The opium myth interpreted these critiques as Chinese people’s unyielding resistance to imperialists’ attempt to turn China into a nation of opium addicts. Nevertheless, the authors prove that these alarms were based on Confucian asceticism rather than Han officials’ understanding of the addictive chemical property of opium since some officials expressed similar concern about the popularity of tobacco. In addition, the authors emphasize that the critique of opium by Han officials was related to their desire to restore the scholar-official class to the position of moral authority that it possessed during the Ming dynasty.

The authors suggest that the opium myth, which emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, was a confluence of two trends. The first is the prevalence of opium prohibition in Europe from the 1870s. Opium prohibition was “part of the medical profession’s search for moral authority, legal control and statutory power over pharmaceutical substances in their fight against a popular culture of self-medication.” The second is Chinese nationalists’ effort to defend their own country from the encroachment of imperialism. The nationalists were eager to figure out why China was repeatedly defeated by imperial powers. The authors suggest that the Chinese nationalists viewed opium smoking as the origin of national weakness rather than a personal behavior and that they saw anti-opium campaign as a useful tool to save China from a world dominated by imperial powers.

The authors’ second conclusion is that the anti-opium campaigns, rather than the opium itself, brought miseries to opium smokers. The anti-opium campaigns transformed the public image of opium smokers from gentlemen to thieves, swindlers, and beggars who were enslaved by powerful chemicals. These campaigns also transformed opium houses from a culturally sanctioned venue for male sociability into a site of perdition, a marker of uncivilized behavior and barbarism where vulgar and despicable addicts were leading the country to complete extinction. The prohibition laws passed in these campaigns gave authorities the right to arrest, punish, and kill opium smokers. Besides creating a criminal underclass, these campaigns also pushed smokers from moderate opium to more addictive and more harmful semi-synthetic opiates like morphine and heroin. Even worse, these semi-synthetic opiates are consumed in a much more harmful pattern: heroin and morphine were usually mixed with other unknown compounds and snorted, chewed, or injected with dirty needles shared by many addicts without any protection.

There are some omissions in this book. The first is the process by which the opium myth gained its concrete shape. The authors do a great job in deconstructing the opium myth but fail to dedicate enough attention to this process. This omission weakens the credibility of their argument. The second is the role of racism in the anti-opium campaigns. Opium smoking was mainly a habit practiced by Chinese and Indian. Racism against Chinese immigrants in the United States is responsible for linking opium smoking as a Chinese behavior with opium smoking as a barbarian behavior. Some Chinese intellectuals might accept the anti-opium ideas without any awareness of the racism behind it. The absence of the discussion of racism makes this book less useful than it is supposed to be in understanding how Chinese intellectuals changed their way of thinking through their interaction with the Western world. Furthermore, the authors’ conclusion that the anti-opium campaigns facilitated the spread of the semi-synthetic narcotics is also questionable. After the collapse of the Ch’ing Dynasty, some places of China witnessed the prosperity of both opium and semi-synthetic narcotics. This prosperity could not be explained just with the pressure of the anti-opium campaigns. Despite these omissions, Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China serves as essential scholarship for the researchers of modern Chinese history. It re-interprets opium use in Chinese society from the sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth century and shatters one of the most important pillars of the conventional narrative of modern Chinese history. It reveals the complexity of modern Chinese history and implies the failure of the conventional narrative in addressing this complexity. The book throws lights on opium smokers’ miseries caused by the anti-opium campaigns and reminds readers that some important stories are crushed and abandoned in the writing of modern Chinese history. Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China also indicates the significance of culture in shaping public opinion about narcotics and encourages readers to reconsider the effectiveness of the restrictive prohibition law in dealing with the spread of narcotics.

You May Also Like:

Peeping Through the Bamboo Curtains: Archives in the People’s Republic of China

Great Books on Women’s History: Asia