Not Even Past republishes this moving and insightful article on returning to Texas by Jonathan Cortez to celebrate them joining the faculty of the Department of History at UT Austin as an Assistant Professor of Borderlands History. Dr. Cortez wrote this piece about returning to Texas to teach after 10 years on the East Coast while serving as an Early Career Postdoctoral Fellow. The History department officially welcomes Dr. Cortez with delight.

During my first weekend back in Texas I waded into the Río Nueces.

Torrential rain the night before caused record flooding. My body, buoyed by the rushing water, could barely reach the rocks below. Looking downstream, I watched the flood pass over and submerge the man-made barriers meant for passing cars. The flood now mended what was once an interruption of the river caused by the building of the highway in 1919. Vehicles paused as brown-skinned people floated by on rafts, tubes, and kayaks. The energy was relaxed and convivial.

Water meets land and is reminded of its duties.

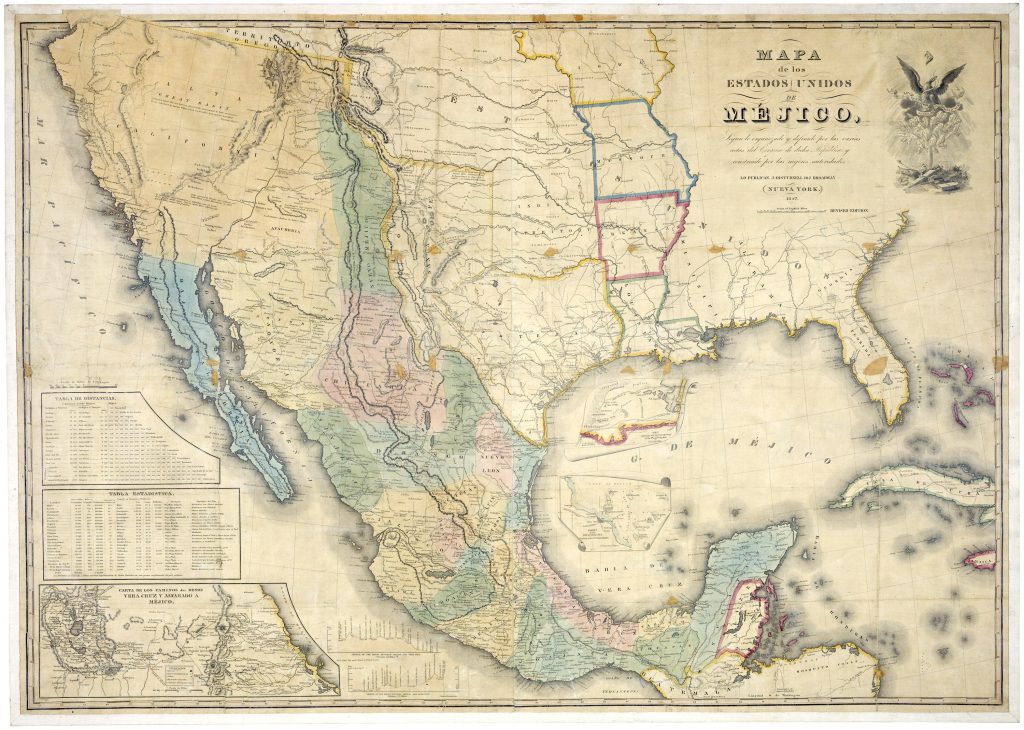

Stretching for 507 kilometers along the southeast of current-day Texas, the Río Nueces has a long history to be learned. Various indigenous tribes of the ancestral Coahuiltecan peoples including the Pacuaches, Sacuaches, and Tepacuaches concentrated their livelihoods around the Nueces as early as the late 1500s. But they were forcibly thinned and dispersed by the imperial forces of Spain, Mexico, and eventually the United States. In the late eighteenth century, second-generation Spanish conquistadors and colonizers such as Blas María de la Garza Falcón and Alonso de León traveled into this region and settled ranching outposts to be used by Spanish soldiers and missionaries for exploration.

Under Mexico’s tutelage during the mid-nineteenth century, the Río Nueces became a highly contested natural boundary between Mexico’s northern state of Tamaulipas and an in-limbo Texas Republic. Whereas Mexico claimed the Río Nueces as their northern divide, Texas claimed the Río Grande as its southern territorial demarcation. However, since neither side could undeniably claim what has been referred to as the Nueces Strip – the land between the two rivers – Texas received assistance from the United States to achieve its territorial goals.[1]

The 240-kilometer Nueces Strip played an important role in the institution of slavery and influenced the rivalry between the two interests. Slaveholding Anglo settlements in Mexico’s Texas, many of which U.S. citizens established by uprooting their families and African captives from states like Virginia and the Carolinas in response to promises of vast lands and prosperity, grew angry after Mexico abolished slavery in 1829. Over time, Texas wedged itself off politically and culturally from Mexico, and by 1845, the United States had consumed Texas, bringing it into its union.

As abolitionist intellectual and refugee Frederick Douglas orated in Belfast, Ireland on January 2nd, 1846, “Here [the United States’ annexation of Texas] was an act of national robbery perpetrated, and for what? For the re-establishment of slavery on a soil which had been washed pure from its polluting influence by the generous act of a ‘semibarbarous’ people!”[2] Between 1846 and 1848, the United States entered into war with Mexico over these boundary disputes, which ended with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. By the end of this conflict, Mexico was forced to cede fifty-five percent of its territory and accept the Río Grande as the divide between the two countries. Slavery was reinstated in the Nueces Strip.

My body, submerged in water, is reminded of an entangled past.

I was visiting a prima in Uvalde my first weekend back in Texas when we decided to spend the day on the Río Nueces, sixteen kilometers from the city center. She moved there a few years earlier for a job and found comfort in the town’s quaint lifestyle and in the possibilities for her and her girlfriend to make a home amongst other ethnic Mexican working-class people. A community in mourning, Uvalde was the town where, three months earlier, an 18-year old former student purchased a military-grade weapon, entered Robb Elementary School, and proceeded to murder twenty-one students and teachers. The incident devastated the town where over seventy percent of residents identify as “Hispanic” – and more specifically, as “Mexican American.”[3]

Grieving parents from Uvalde now lead the charge for gun reform in Texas, hoping to eliminate any chance of tragic reoccurrence without the need to increase police presence in their schools.[4] Robb Elementary was also the origin site for the 1970 Uvalde Chicano Movement in opposition to Mexican American discrimination, which caused reverberations and Chicano uprisings throughout the region.[5] If this small town has taught us anything, it is that its residents have always understood how their struggles for autonomy connect to those of other ethnic Mexicans in South Texas. These legacies of violence and resistance echo all along the Río Nueces.

We are all trying to survive the aftermath of the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo.

I grew up where the Río Nueces empties into the Gulf of Mexico. Robstown, Texas, to be exact. My family members have lived their entire lives inside this contested territory, bordered by the Río Nueces and the Río Grande. We didn’t go north past San Antonio or south past Matamoros—at least while I was an adolescent. Before my time, my family was largely migratory. In January 1960, when my dad was just five years old, my grandmother brought him and his four siblings to Texas from Sandoval, Tamaulipas, Mexico. They were asked to pose as a group in their passport photo, and each of their documents holds the exact same picture.

Once in the United States, they used seasonal migrant farmworker routes to travel from South Texas to the San Joaquin Valley, picking onions, tomatoes, cucumber, and other produce. My mother, born in Texas during the 1950s, was a child of Mexican immigrants who migrated to the South Texas region during the 1920s – a period of massive Mexican farmworker migration into the U.S. – from Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico. They lived in Texas in an age when it was illegal to speak Spanish in schools and doing so was punishable by force. Juan Crow laws determined where ethnic Mexicans could live and learn, and society deemed them incapable of intellectual pursuits, relegating them to farmwork or cannon fodder

I left South Texas to pursue a Ph.D. in American Studies at Brown University. Leaving Texas seemed like the best option for gaining the analytical framework needed to better understand the conditions and context under which I was raised. Before this move, I attended the University of Texas at Austin and earned my bachelor’s degrees in Sociology and Mexican American Studies. I learned Texas and U. S. History through the lenses of Ethnic Studies and Mexican American Studies. Everything that the Texas Legislature conveniently forgot to include in my K–12 public school curriculum was laid bare.

I could no longer be a complicit participant in the myths into which I had been unknowingly raised since childhood – American exceptionalism, patriotism, capitalism, the gender binary, patriarchy, (trans)misogyny, anti-Blackness, and anti-indigeneity. I left for the East Coast to leave those constructs behind, not because they don’t exist in New England but because I needed to uproot myself from the horrors of internal colonialism deeply entrenched in this specific geographical location that I knew so well. Instead, I made the choice to engage with theories of liberation, histories of the oppressed, and to make deep work of epistemological shifts from afar.

If I am not careful, I lose my footing.

After almost ten years away, I return to Texas to take up the position of Provost Early Career Fellow in Borderlands History at UT Austin’s Department of History. My route back to this place, where my intellectual curiosities began, has been circuitous. Continuing my work, I will research, write, and teach histories of immigration, ethnic studies, Latino studies, and borderlands studies. Further, my commitment to working with South Texas communities on public history initiatives is central to my pedagogy as a professor at a flagship university. In many ways my research, writing, and public-facing work are situated in the aftermath of the struggle over the Río Nueces and the Río Grande as national divides – a struggle with important implications for migration, labor, and racialization.

My book, The Age of Encampment, focuses on the history of migrant camps along the U. S.–Mexico border from the late nineteenth century to the late twentieth century. As issues related to the national divide came continuously to define the United States and Mexico, so too did the makeshift and federally-funded encampments that dotted both sides come to delineate the plight of migrants. In the book I take up the history of Chinese migrant fugitive encampments during the era of Chinese Exclusion, the story of Mexican refugees placed into camps during the Mexican Revolution, the establishment of labor camps along the border during the Great Depression and New Deal, the transformation of these camps for the purposes of Japanese incarceration during World War II, and the shift into the militarized border encampments during the late twentieth century – and which we now inherit.

But still, the water remembers my name, and whispers.

Taking up residence at UT Austin is therefore a returning of sorts: a returning to Texas, the land that my family has traversed for generations; a returning to landscapes of resistance forged by kin in search of colonialism’s trap door; a returning to spaces that are so deeply infused with colonial violence that a dip in the Río Nueces turns into an identity crisis (and an NEP article); a returning to the classrooms that inspired my urge for consuming and creating knowledge about Mexican Americans, South Texas, and the border; a returning to the halls where borderlands thinkers such as Américo Paredes, Rolando Hinojosa-Smith, Neil Foley, and Gloria Anzaldúa moved the field of Borderlands Studies towards academic legitimacy; a returning to the very place where marginalized students who I seek to mentor and teach search for answers on ancestry, on identity, and on being; a returning home.

In the Río Nueces my first weekend back in Texas, I took a deep breath and plunged into the water.

Dr. Jonathan Cortez is at present the Early Career Provost Postdoctoral Fellow of Borderlands History in the Department of History at The University of Texas at Austin. Previously, they held the title of César Chávez Provosts’ Postdoctoral Fellow (2021-2023) in the Department of Latin American, Latino, and Caribbean Studies at Dartmouth College. Their current manuscript, The Age of Encampment, details the history of vernacular and federally-funded migrant camps along the U.S.-Mexico border for the purposes of perceived national security, capital accumulation, and labor control from the late 19th century to the late 20th century. The Immigration and Ethnic History Society, the Western Historical Association, and the American Historical Association have given high recognition to their work. Read about their work at: https://historiancortez.com/.

[1] For information about the history of the ancestral Coahuiltecan, see: Native American Peoples of South Texas, edited by Bobbie L. Lovett, Juan L. González, Roseann Bacha-Garza, and Russell K. Skowronek (Edinburg: The University of Texas – Pan American, 2014), 13-22; Thomas N. Campbell, “Pacuache Indians,” Handbook of Texas. For information on Spanish colonizers, see: Clotilde P. García, “Garza Falcón, Blas María de la,” Handbook of Texas; Chipman, Donald and Harriett Denise Joseph, Notable Men and Women of Spanish Texas (Austin, University of Texas Press, 1999).

For information on the Nueces Strip, see: Durham, George. Taming the Nueces Strip: The Story of McNelly’s Rangers (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982). Author note: The U.S. Army, Texas Rangers, and other U.S. officials have historically used the term ‘Nueces Strip’ to place their fears on a specific geographical location, which they saw necessary to control for Manifest Destiny. However, this piece uses the term to demarcate the land between the Río Nueces and Río Grande and to highlight, instead, the violence U.S. officials did to indigenous peoples and other racialized bodies in the region.

[2] Frederick Douglass, “Texas, Slavery, and American Prosperity: An Address Delivered in Belfast, Ireland, on January 2, 1846,” Belfast News Letter, January 6, 1846; Blassingame, John (et al, eds.). The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One–Speeches, Debates, and Interviews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), Vol. I, p. 118.

[3] U.S. Census Bureau (2021). Uvalde County, Texas Quick facts. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/uvaldecountytexas#qf-headnote-b

[4] Gamboa, Suzanne. “Families of victims of Uvalde massacre call for legislation amid more gun violence.” NBC News. January 24, 2023; Gibson, Caitlin and Clyde McGrady. “The prospect of more police at schools is no comfort for Black parents.” The Washington Post. June 3, 2022.

[5] Cabrera, Kristen and Shelly Brisbin. “How a school walkout in Uvalde helped spark the 1970s Chicano rights movement.” Texas Standard. May 31, 2022; García, Uriel J. and Jinitzail Hernández. “Before the school shooting, Uvalde was known for a 1970 Hispanic student walkout. Its aging participants fear its spirit and memory are fading.” The Texas Tribune. June 22, 2022.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. Although we strive to ensure that articles contain factual information from reliable sources, Not Even Past does not take responsibility for any errors or omissions