Archives, especially state archives, have political agendas. Whether private or public, holdings of individual, institutional, and government documents can serve to invade and control the lives of citizens and societies. Their organizations shape historical knowledge and national narratives about the past. Kirsten Weld addresses these political issues of government intrusion, historical memory, and archival knowledge production by focusing on The Project for the Recovery of the National Police Historical Archives in Guatemala (The Project). Weld identifies two different political agendas structuring the National Police Archives from its professionalization in the 1950s until the state of decay in which it was found in 2005. The first agenda served the purpose of surveillance and social control, using archives as a weapon against people considered enemies of the state during the Guatemalan Civil War between 1960 and 1996. The records’ rescue gave these archives a new social purpose geared towards democratic opening, historical memory, and the pursuit of justice for victims of the state’s war crimes. The book chronicles the transition from the first political agenda into the second with the goal of capturing the process through which a new historical narrative about the war was produced.

Weld argues that how people think about archives is critical to understand their role in the generation of new historical narratives. Archival holdings are also telling about the relationship between citizens and the state in the construction of these national histories. The Project helped transform negative perceptions of archives as dumpsters that perpetuate silence and political apathy, into treasures seen as tools for democratization and empowerment. The author combines historical and ethnographic perspectives to understand how the Police Archives transitioned to a new agenda of democratic opening and citizen’s accountability for crimes perpetuated by the state during the Civil War.

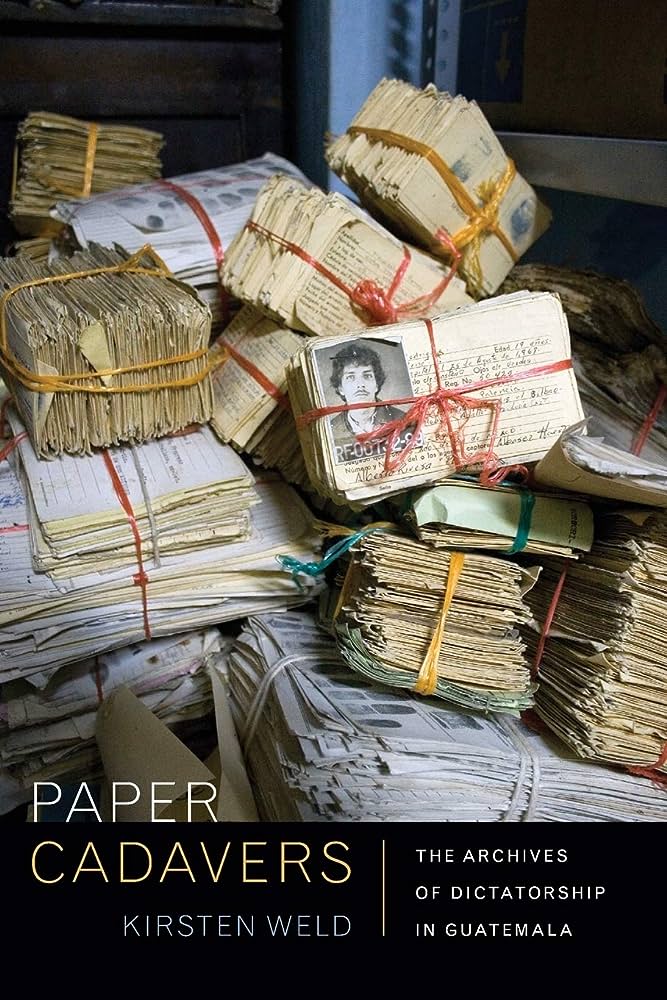

Weld uses ethnography and oral histories to explore how The Project came to be, the tensions that erupted between older and new generations working at the Police Archives, and the dangerous political context in which they had to work. She shows how former guerrilla fighters began an uncertain effort to recover the police archives until the institutionalization of the initiative through foreign funding. Due to the messy and decaying state of the police documents, archival preservation required former guerillas to learn concepts of original order, provenance, and chain of custody in order to know how the National Police organized information. Therefore, the norms outlined in the International Standard for Archival Description would undergird the new organizational logic of The Project from the onset.

Working in The Project also entailed understanding the goals that drove people to get involved with the Police Archives in the first place. Weld shows that former revolutionaries were driven to work on The Project by powerful experiences of loss and militancy, fueled by the desire to restore honor and agency to the dead. The young people she studied who came from militant families saw the preservation of police documents as a new way to continue the revolutionary struggle. To those without revolutionary ties, the archives represented a way to put academic training to use and to advance in the recovery of historical memory and truth telling. These experiences will shape the legacy of the Guatemalan Civil War and the next generations’ interpretations of the past.

The growing visibility of this collaborative effort, however, made it the target of military pressures, which raised concerns about the welfare of the archives and its personnel. This threat of violence was not new and was preceded by what the author calls “the archival wars,” — battles between citizens and the state over the access and meaning of state documents. Weld presents the different strategies rulers and ruled have used since the beginning of the Civil War to limit or expand access to records. These include legislation to block or undermine the preservation of state information, the demand to know what information the state holds about a particular citizen, or the successful publication of reports about disappeared Guatemalans.

Drawing from state archives and human rights reports, Weld also focuses on the institutional history of the National Police. The restructuring of this institution from 1954 to 1974, through counter-insurgency aid from the U.S, led to the establishment of efficient record keeping systems as a means to enact effective social control. The Central Records Bureau and the Regional Communications Center are just two initiatives that helped the Guatemalan state monitor its citizens. Better archives, modern equipment, and professional personnel became synonymous with the battle against “subversion.” This counterinsurgent mentality of the police accounted for most of the urban violence in the 1980s. The transition to democracy in 1986 perpetuated the counterinsurgency approach into the post-conflict period, explaining the militarized and centralized nature of the new National Civil Police.

Finally, the author delves into the successes and risks that the new archival agenda of social reconstruction and historical revisionism faces in Guatemala today. By working toward the passage of national archives system laws, and creating archival science programs in national universities, the Project has inaugurated a new archival culture in Guatemala, one that seeks a more democratic and transparent relationship between government and citizens. But the military’s institutional opposition to The Project reveals resistance to a new historical memory that subverts old narratives of a triumphant nation against communism.

Weld combines an impressive set of written sources with an ethnographic approach and oral histories of people who worked in the Project. These sources serve her well in capturing the transition from one archival agenda to the other. The author’s writing style is clear and fluid. This is a critical study that intertwines new interpretations about urban violence in Guatemala with a growing literature on historical memory and the politics of state archives in post-conflict societies.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.