By Adam Clulow

This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

For more than a decade now I have been researching and teaching about the Amboina (Amboyna) trial. This was an enormously controversial conspiracy case that took place on a remote island in Indonesia but involving a global list of characters including Japanese mercenaries, English officials, Dutch merchants, slaves from South Asia and local polities. In 1623, Dutch authorities accused a group of English East India Company merchants and Japanese soldiers of plotting to seize a Dutch East India Company fort and with it control over the trade in precious spices. The alleged conspirators were arrested, tortured and based on their confessions subsequently executed. By the time the trial concluded, a total of twenty-one men were dead, beheaded by Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) authorities.

The trial is important for two reasons. First, there is a still unresolved question over the guilt or innocence of the alleged conspirators. For close to four hundred years now, scholars and popular writers have been debating just what happened on this island: who was guilty, who was innocent and what it all means. Historians writing in English have generally insisted that no plot existed and hence that the VOC had no basis to execute a group of English merchants and their supposed Japanese collaborators. In contrast, most Dutch historians argue that there was some sort of conspiracy and, because of this, that the Company had every right to take judicial action.

While this debate shows no signs of ending, Amboina is also important for a second reason: it became the centerpiece of a long propaganda campaign waged by the English East India Company that turned what happened on this remote island into a symbol of Dutch treachery, cruelty and betrayal.

The trial

The Amboina case generated a vast archive of court records, depositions and other materials spanning more than five thousand pages. But because so many witnesses were on the payroll of either the Dutch or English companies, the archive offers little clarity about the possible conspiracy and the trial itself. Instead, putting together the different versions of the case creates a dizzying Rashomon-like kaleidoscope of possible interpretations. While working on what would become my book, Amboina, 1623: Conspiracy and Fear on the Edge of Empire, I decided to develop a specialized teaching website designed to take the case into the classroom.

My impetus for this website came from watching my students talk about a long-concluded trial in a different part of the world. What I was witnessing was the remarkable worldwide response to the groundbreaking first season of the podcast Serial, which focused on a 1999 murder case in Baltimore. Serial became the most downloaded podcast in history, and it generated a tremendous response as the public logged vast numbers of hours working through the key pieces of evidence.

Listening to Serial, I began to wonder if I couldn’t do something similar (on a far smaller scale) for my classroom: what would it be like to make primary source documents related to the 1623 trial freely available for students to dig into and interpret, putting forward their own conclusions about what happened? Working with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, I built an interactive website, The Amboyna Conspiracy Trial, designed to do just that.

At the heart of the site is an interactive trial engine which places students at the center of the case. To make a complex trial more accessible, we boiled the controversy down to six key questions that have to be answered one way or the other in order to come to a verdict. For each question, the site presents the arguments mobilized by both sides, the prosecution and defense, in conjunction with the most important pieces of evidence, related documents and legal commentary from a distinguished trial attorney. In addition, we created a large repository of additional material and documents, which students can work through at their own pace to support their conclusions.

The site became the centerpiece of classes I taught on the rise of the Dutch and English chartered companies in the seventeenth-century and their competition over precious spices. Students were challenged to work through large quantities of seventeenth-century primary source material online before taking on one of four roles—Barrister (Attorney), Witness, Researcher or Judge—in a comprehensive and competitive examination of the original trial. The exercise produced some of the most exciting classes I have taught. Students pored over the minutiae of the case and came to class prepared to debate their conclusions.

The trial exercise proved so successful in part because it harnessed a familiar genre: True Crime and the dissection of a single criminal case and subsequent trial. Students know this genre intimately, and once they are confronted with an archive of this kind I have found that they tend to dive right in. But Amboina is also important because it seeped into the English popular imagination for decades after the trial concluded. This part, the long legacy of the Amboina trial in print and image, has always been far more difficult to teach.

The long legacy

When news of the case reached Europe around May 1624, it sparked immediate outrage. Passions were inflamed by the publication of a slew of incendiary pamphlets on both sides that sought either to damn the Dutch as bloody tyrants or condemn the English as faithless traitors. While both companies pushed their own version of the case, the English East India Company scored the greatest successes. By any measure, the English East India Company waged an extraordinarily successful propaganda campaign against its Dutch counterpart. This is brilliantly discussed in Alison Games’ recent book, Inventing the English Massacre: Amboyna in History and Memory, which shows how successive generations of English writers came to invoke “Amboyna as a shorthand to convey cruelty and betrayal without comment or elaboration, so certain were they that their readers would understand the significance of the word.”

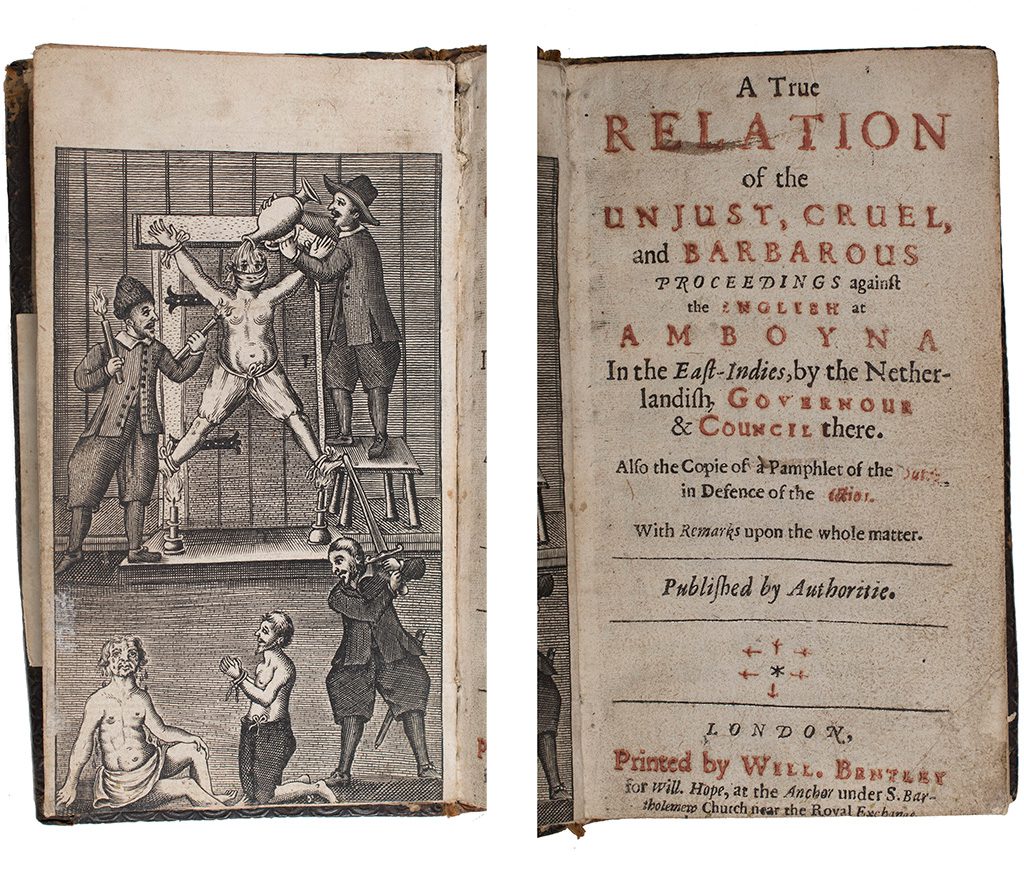

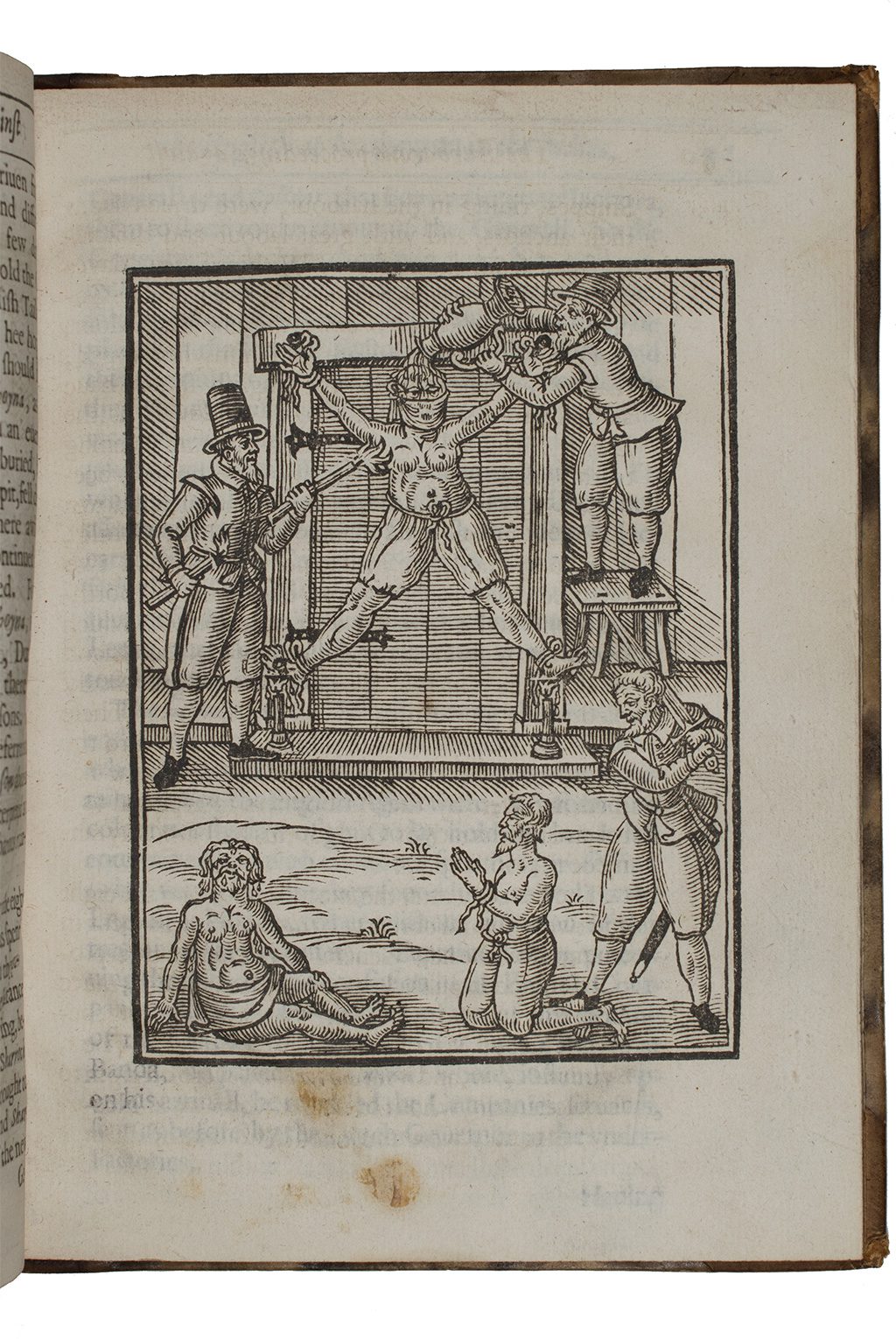

The propaganda campaign took many forms. The English East India Company commissioned a “very large picture, wherein is set forth those several lively, largely artificially bloody tortures and executions inflicted upon our people at Amboyna.” But its key instrument was a printed pamphlet, a relatively cheap publication that was printed again and again, often with an illustration of the English being brutally tortured.

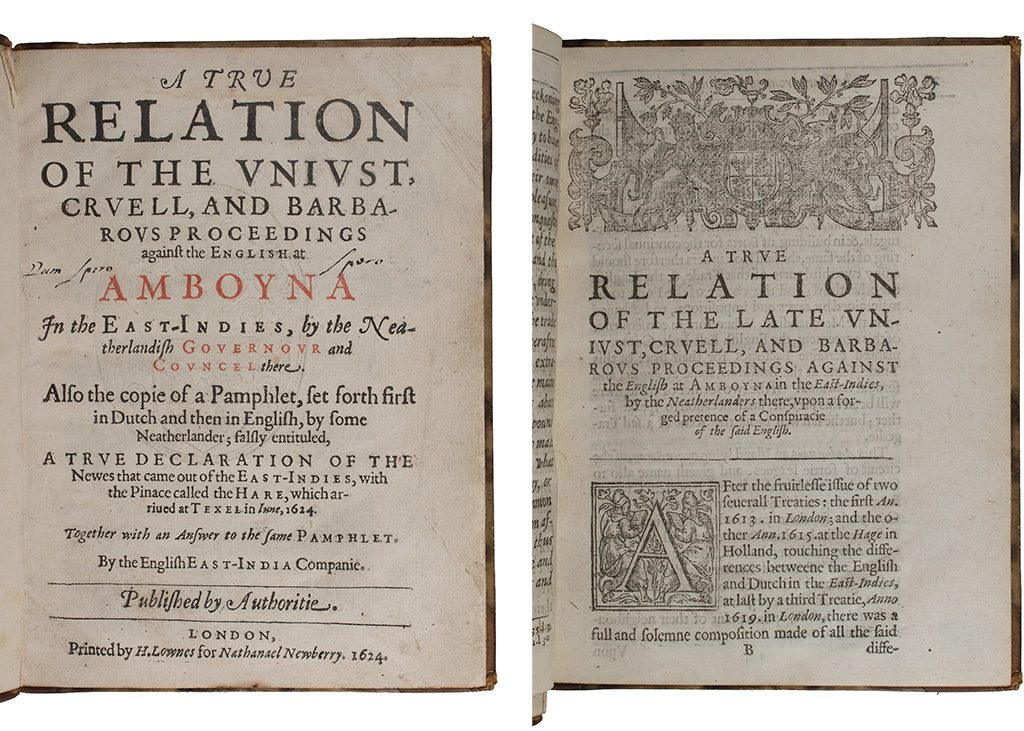

The first shots of the pamphlet war were fired by VOC supporters in a short publication, Waerachtich Verhael vande Tidinghen ghecomen wt de Oost-Indien, that was first published in July 1624 and later translated into English as A True Declaration of the News that Came Out of the East Indies. Widely believed to be the work of a senior Dutch official, it denounced the “abominable conspiracy” while offering a measured defense of the legal proceedings. The English Company was quick to respond, commissioning A true relation of the unjust, cruell, and barbarous proceedings against the English at Amboyna in the East-Indies, by the Neatherlandish gouernour and councel there, which was compiled on the basis of the testimony provided by the handful of survivors of the trial who had made their way to England.

True Relation proved an enormously successful and durable text. It took a complex trial and turned it into a straightforward and compelling story in which the “unsatiable covetousnesse of the Hollanders” had driven them to engineer a “cruell treacherie to gain the sole trade” in precious spices. It reimagined a disparate and largely undistinguished group of British merchants as pious martyrs united by their Protestant faith and it included a potent woodcut image showing an unnamed English merchant being tortured with water and candles while another kneels in prayer, ready for execution. As Anthony Milton has shown, such depictions, which seem to have drawn on an early edition of John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, confirmed the English in Amboina in their new role as righteous martyrs. The 1624 True Relation was endlessly printed, modified, retitled and reprinted for the rest of the seventeenth century, making it an extraordinarily successful weapon in the English Company’s campaign to place blame and win compensation for what had happened on Amboina.

While these printed books underpinned a sharp deterioration in Anglo-Dutch relations, it is a struggle to get students interested in poor-quality PDFs of old pamphlets. In Spring 2020, however, I tried something different. With Aaron T. Pratt, the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at the Harry Ransom Center, I combed through the Center’s vast collection for everything connected to Amboina and laid out what we found around a group of large seminar tables.

It proved a revelation. By the time we were done, the students could see before them in concrete form an extraordinarily successful propaganda campaign as represented by a series of interlocking texts that all borrowed from each other. Beginning with the 1624 True Relation, the display showed how an image was formed, how it was entrenched with key symbols and how it was subtly manipulated over time, appearing each time in a slightly different form. In 1651, for example, the same basic pamphlet was reprinted for a new audience.

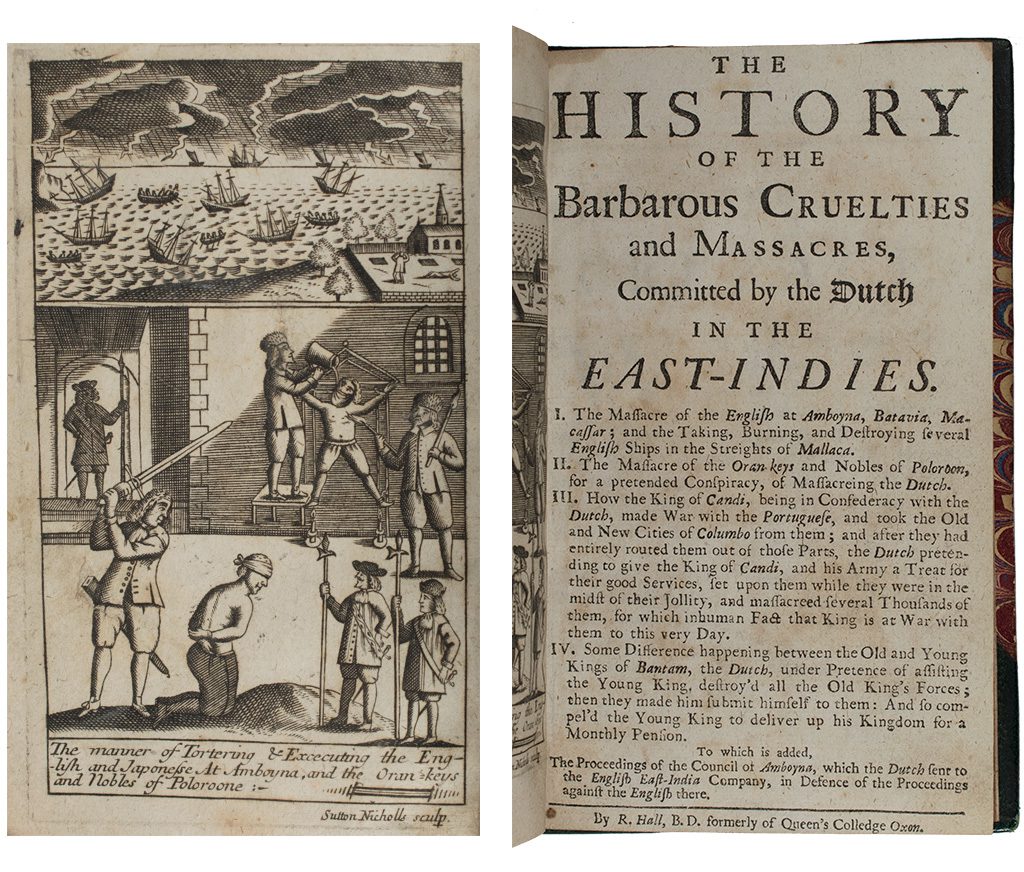

In 1665 it was republished again, and in 1672, close to fifty years after the original trial, a new version promised to reveal “the naked truth of this cause, hirtherto masked, muffled and obfuscated”.

True Relation spawned a host of sub-texts, too. In 1673, for example, John Dryden wrote the charges against the Dutch into a play, Amboyna: A tragedy. Damning the Dutch as bloody murderers, the play gave a new generation the chance to discover, as one stage direction put it, “the English tortured, and the Dutch tormenting them.” And Dryden threw in new crimes, accusing the Dutch of rape and cannibalism.

By the 1680s, Amboina had not lost its potency even though half a century had passed since the trial itself. The Center has a remarkable text from 1683 entitled Unparallel’d varieties: or, the matchless actions and passions of mankind. Displayed in near four hundred notable instances and examples. This introduced a new and evolving image of Amboina. Here the English were not simply righteous martyrs. Instead, their judicial murder had been marked by a sign of divine wrath from the heavens. In this retelling, which drew from part of the True Relation but gave it new form, the execution of the English merchants in Kota Ambon was accompanied by “a great darknesse, with a sudden and violent gust of winde and tempest” that almost wrecked the Dutch ships clustered in the harbor. This was followed by a terrible illness that “swept away about a thousand people, Dutch and Amboyners.” The meaning of such signs was unmistakable. They were “a token of the wrath of God for this barbarous tyranny of the Hollanders.” In 1683, all of this was included in a new image paired alongside one drawn from the original 1624 woodblock print. Like its predecessor, this image had a long life and was reprinted in 1712 as part of a new text, The History of the Barbarous Cruelties. There can be little question as to what it would have meant to the reader. Here we see God’s wrath at the top of the image in response to what the Dutch have done in the lower half.

We live in a digital world. This trend has become even more pronounced now as the COVID-19 pandemic has forced us out of in-person seminar spaces and into Zoom classrooms. But there remains something immensely powerful about encountering original documents right in front of your eyes, in seeing how an image morphs and evolves in print and in standing around a table with a series of interlocked texts arrayed in front of you. This is the joy of having something like the Ransom Center on campus. It is a reminder of how lucky we are as historians to have this incredible resource available to us and our students.

Adam Clulow is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of The Company and the Shogun: The Dutch Encounter with Tokugawa Japan (Columbia University Press, 2014), which won multiple awards including the Jerry Bentley Prize in World History from the American Historical Association, and Amboina, 1623: Conspiracy and Fear on the Edge of Empire (Columbia University Press, 2019). He is creator of The Amboyna Conspiracy Trial, an online interactive trial engine that received the New South Wales Premiers History Award in 2017, and Virtual Angkor with Tom Chandler, which received the Roy Rosenzweig Prize for Innovation in Digital History.

![John Foxe, The first [-second] volume of the ecclesiasticall history, contayning the Actes & monumentes (London: John Daye, 1576), sig. TT6v. Harry Ransom Center Book Collection, -q- BR 1600 F6 1576.](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Primary-Source-2020-11-Image-03.jpg)