This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

Wednesday the 20th of September 1809 was not a good day for Richard Glasspoole. For one, he woke up stranded in a boat, with the wind threatening to blow him towards an uninhabited island somewhere in the South China Sea. There were also eight other people in the boat with him, and it was their third day crowded together. Fortunately for Glasspoole, Wednesday would be the last day he would spend in the boat. The same day, Richard Glasspoole was captured by pirates.

The account of what happens next was published in an intriguing volume now held at the Harry Ransom Center.

Piracy had been present in East Asian waters for centuries. From the wakō pirates of the 14th to 16th centuries who raided Chinese and Korean coastal settlements, to the Noshima Murakami of the Seto Inland Sea who claimed legitimacy and charged a fee for passage through their waters, East Asian piracy had passed through numerous waves. By the time Glasspoole and the others in his cutter were captured, piracy, especially in the South China Sea, was dominated by a single intriguing but also elusive figure: Zheng Yi Sao, a name that can be translated simply as Wife of Zheng Yi. Her rise from being sold as a sex worker in Canton to pirate queen of a fleet numbering 70,000 pirates makes her arguably the most successful pirate in history.

In 1801, Zheng Yi Sao was either captured by pirates or joined them voluntarily, depending on the sources one prefers. Either way, she married a pirate captain named Zheng Yi, and took over running the administrative side of his fleet. At this point, the pirates that would one day form Zheng Yi Sao’s confederation belonged to distinct groups, with their own leaders, grudges, and target preferences. They had been privateers licensed by the Tây Sơn dynasty in Vietnam to fight against Qing China. When that dynasty collapsed, the former privateers decided to make the transition into full-fledged piracy. After three years of disorganization and chaos, the pirates eventually united under the Guangdong Pact of 1805.

In this pact, the pirates agreed to a remarkable level of regulation and bureaucracy. For example, the pirates were now divided into separate squadrons, each identified by a differently colored flag. Each vessel was also required to have a registration number to be painted on its bow. This is a surprising level of organization for a pirate fleet given that pirates were ostensibly attracted to the prospect of living outside of normal societal conditions. For example, if the ships had registration numbers, then there must have been a ship registry and a registrar whose job it was to keep accurate records. When we think of pirates, we probably think of raids, sword fights, cannons, and adventure—not the image of someone hunched over a desk sifting through records .

Zheng Yi Sao was not a signatory to the Pact of 1805, but at this point she had been married to Zheng Yi for four years, and had become a powerful figure within his fleet. We do not know her precise role in crafting the pact or what ideas that Zheng Yi voiced actually came from his wife. When Zheng Yi died in a storm in 1807 and Zheng Yi Sao took power in the Guangdong Confederation, she wrote a new pirate code of her own, which bore some striking resemblances to the Pact of 1805. It is probably safe to say, therefore, that, at the very least, she recognized the value of certain ideas in the pact.

A key provision of Zheng Yi Sao’s code was the formalization of the distribution of plunder and wealth. Whenever a ship or squadron took a prize, that force got to keep twenty percent of the plunder as a bonus. The remaining eighty percent would become part of the common fund and was used for the maintenance and resupply for the entire fleet. This rule managed to balance incentivizing pirates to take loot while also ensuring enough supplies for the entire fleet. The effect of this was that even unsuccessful ships were well supplied and vessels in the Guangdong Confederation were always able to bring their full force to bear, without having to worry about conserving ammunition. Despite a fleet of over 1,200 ships and 70,000 pirates, Zheng Yi Sao found a way to keep all ships armed and all pirates fed. Such a logistical achievement, illustrates both how accomplished the Guangdong Confederation was at taking prizes, and the sheer administrative powers of Zheng Yi Sao herself. To a sailor, especially a pirate, in the early 19th century, knowing that they had food and fresh water for the next few weeks at least provided the confidence and security needed to sail into danger.

Why then, if Zheng Yi Sao’s fleet was so powerful and her fortune so vast has she been forgotten when most people talk about pirates? Misogyny and historiograpical biases obviously play a role. Historians studying pirates have typically focused on the so-called “Golden Age of Piracy” in the Caribbean, with figures such as Stede Bonnet, Blackbeard, and Henry Morgan occupying the popular imagination. Some historians who have written about the Guangdong Confederation, have tended to leave Zheng Yi Sao out of the narrative, and instead focus on her adopted son/husband Zheng Bao. Another challenge to telling her story is the fact that pirates generally did not keep formal log books, and what records the Guangdong Confederation did keep do not survive to this day. This makes it difficult to find primary sources about Zheng Yi Sao’s pirates. Those that do survive were typically written by Europeans who were captured and ransomed writing about their experiences. These captives are obviously not going to be taken to the head of the entire confederation, so most of them only ever saw the leader of a handful of vessels and believed that person to be the one in charge.

This brings us back to Richard Glasspoole and the predicament he found himself in. The capture and ransom of Europeans was fairly standard practice for the Guangdong Confederation. They would seldom engage a fully armed European or American warship in combat, but when a weak or undermanned vessel was isolated, they would use their superior knowledge of the geography to hide behind islands and quickly capture and plunder vessels. Glasspoole and his men, adrift in a lonely cutter, were easy prey.

Glasspoole spent nearly three months as a captive. During that time he witnessed many raids, and even participated in one himself in exchange for a lower ransom price. Glasspoole’s testimony is incredibly valuable in trying to ascertain the everyday life of pirates in the Guangdong Confederation. Most of his correspondence was reproduced in a collection of primary sources titled Further Statement of the Ladrones on the Coast of China originally published in 1812. However, while this text contained an abridged account of Glasspoole’s capture, presented without context or explanation, it was mainly a description of shipboard pirate life.

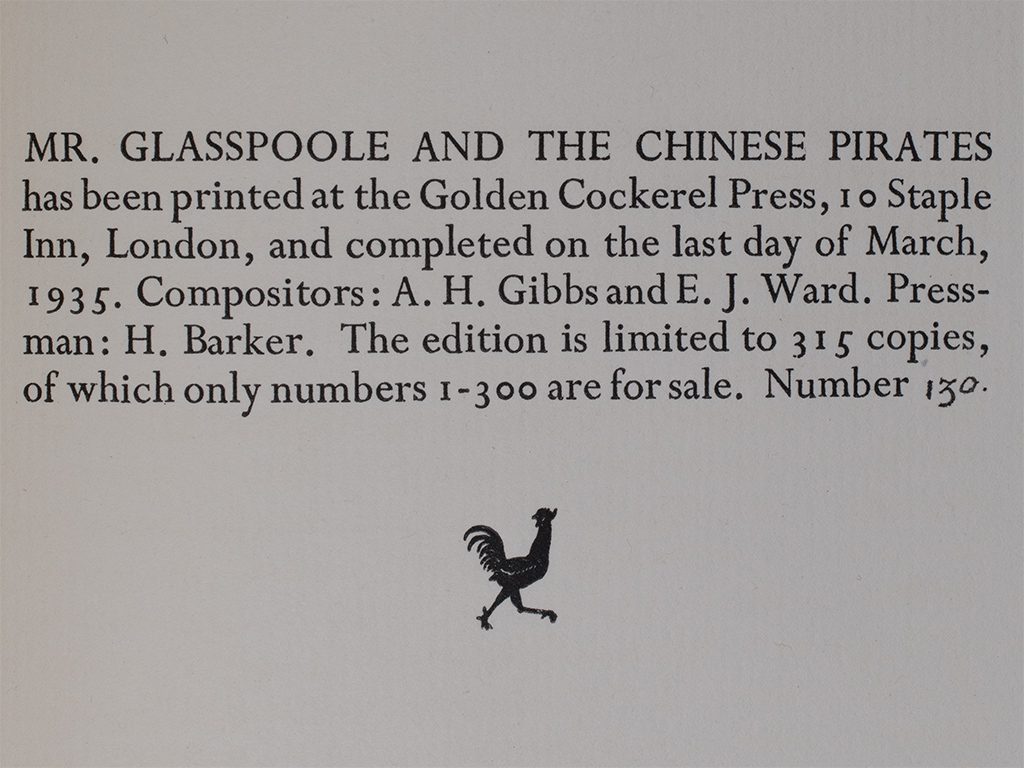

His narrative correspondence was not given careful, exclusive consideration until it was printed by Owen Rutter, Robert Gibbings, and the Golden Cockerel Press. The Golden Cockerel Press was a fine printing press in the UK in the early twentieth century. It began life as a cooperative, yet when it failed to return much money, the original founders decided to shut it down. This angered the wood engraver Rober Gibbings, who was a fan of fine printing and had worked with the press before. Gibbings, saddened by the failure of the business, purchased it for £1,050 in 1924 and became its sole manager. The first book published under his leadership, partially completed when he purchased the press, returned £1,800. Gibbings ran the press through its boom times, managing the printing of and engravings for classic works such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. By the 1930s, however, the Great Depression had hit, and the market for fine printing had collapsed. Gibbings then sold ownership to a group looking to get into the printing world. One of those partners was a man named Owen Rutter. Gibbings stayed on as the press’ manager.

Rutter was a man obsessed with all things maritime. He served as a magistrate in North Borneo, Sabah today, and had fallen in love with the Pacific Ocean. As a partner working with the Golden Cockerel Press, Rutter edited and published several books about the mutiny on the HMS Bounty. Rutter would find primary sources, edit them, and write the introduction, and Gibbings would create engravings. While the engravings may seem mild by today’s standards, in the ’30s they shocked the press’ readers. Their emphasis on violence and, occasionally, erotic imagery became part of the identity of the Golden Cockerel Press. They were willing to publish images that other publishing houses would not. The engravings in the Glasspoole text certainly fit this trend, but they also lean into distinctive sinophobic tropes including featuring a menacing Chinese male figure.

In 1935 the Gibbings/Rutter Pair combined to publish Glasspoole’s narrative account of his capture by Zheng Yi Sao’s pirates, intercut with some excerpts from other relevant documents, such as the captain’s log for the Marquis of Ely, the ship Glasspoole was an officer on, and some of the deliberations on how much ransom to pay for Glasspoole and his crew.

The book itself is striking. The cover is bright yellow, with an illustration of a Chinese pirate repeated in an almost dizzying pattern. The untrimmed and uneven leaves are made of high quality paper, very much in line with other fine press books.

The volume is not a long one, only about fifty pages of print in a large font and with ample margins. And Glasspoole’s narrative only takes up about thirty pages of that. Almost half of the book is given over to Rutter’s introduction, both of Glasspoole and of Chinese piracy in general. Rutter had previously written a book about piracy in the South China Sea, The Pirate Wind: Tales of the Sea Robbers of Malaya, and thought of himself as an expert on the topic.

This period saw xenophobic “yellow peril” imagery that painted China as a terrifying and threatening place. At the same time, there was also considerable sympathy for China as it suffered from Japanese imperialism. Rutter’s introduction walks a line between respect for the Guangdong pirates and outright racist stereotyping.

Crucially, Rutter does acknowledge Zheng Yi Sao as the true power in the Guangdong Confederation. He also includes a shortened translation of her pirate code, taken from an 1830 book by Yung Lun Yuen. Rutter describes Zheng Yi Sao as “a remarkable woman” and praises her for using “her authority with firmness and discretion.” Rutter seems to be sympathetic towards the Guangdong pirates, though he, Gibbings, and Glasspoole all revel in descriptions of village raids.

Rutter also makes some unsubstantiated historical claims, such as stating that the “pirate chief” Glasspoole describes as the leader of the Red Squadron which captured him was likely Zheng Bao. In all likelihood, however, Glasspoole probably never met Zheng Bao or even saw the entirety of the Red Squadron. The man Glasspoole describes as the chief was probably the leader of a collection of a small handful of ships.

Glasspoole’s estimate of the number of war junks in the Guangdong Confederation is extremely low, he estimates 200 rather than the more likely 500, meaning that Glasspoole probably never got a full sense of the scale of the confederation’s operation.

It is likely that the man Glasspoole names “A-juo-Chay” is Zheng Bao, as he says that when this figure surrendered, he did so on the condition of a pardon and to be “made a Mandarine of distinction.” Since Zheng Bao was given a military commission upon his pardon, it seems likely that A-juo-Chay is Zheng Bao, rather than, as Rutter suggests, Zheng Yi Sao. Rutter may well have been an expert on all things HMS Bounty, but he was hardly an expert in the Guangdong Confederation

This is not a scholarly account. Rutter had seemingly read a single book on Zheng Yi Sao and was a maritime enthusiast rather than a historian. He was also looking to sell books. The graphic images described by Glasspoole presented an excellent opportunity for Gibbings to create some of his trademark risqué engravings. Rising tensions in China as Japanese and Chinese forces fought skirmishes before the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 may also have played a role. The introduction paints a picture of Chinese people as ferocious in combat.

Only 315 copies of Mr. Glasspoole were printed, and fifteen were kept in reserve. It is an artifact of two centuries, bound up with the romanticism, ideas, and anxieties of both.

Jacob Parr is an undergraduate majoring in History at the University of Texas at Austin. He is interested in naval history during the age of sail, as well as baseball, both past and present. He is writing his undergraduate thesis on the Texas Navy. Jacob plans to pursue law school in the fall of 2023.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.