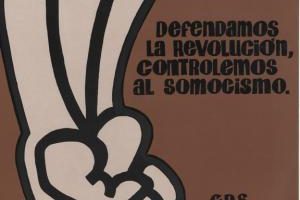

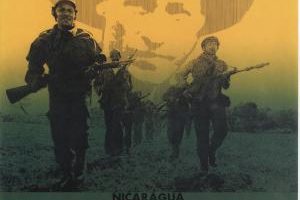

These posters were circulated in Nicaragua in 1980 when campaigns to celebrate the end of dictatorship, to increase literacy and to improve public health were central policy concerns.

On July 19, 1979, the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN or Sandinistas), a leftist movement that drew its support from a wide sector of Nicaraguan society overthrew the dictator Anastasio Somoza, whose family dynasty had ruled the Central American country with ruthlessness and greed since 1936. The Sandinistas established a revolutionary government that was inspired by Karl Marx and Fidel Castro but was also deeply influenced by Catholic ideas of social justice.

The ascendency of Ronald Reagan to the US presidency in 1981, however, placed the Sandinistas squarely in the crossfire of the new Cold War. Pressure from the United States (especially the US-supported contra war) and Sandinistas’ missteps, along with growing disillusionment of Nicaraguan society, brought about the end of the regime in 1990, when the Sandinistas were voted out of power in a free democratic election.

Although the Sandinistas ultimately proved a disappointment to both the supporters and the opponents of the regime, the early days of their rule were full of optimism and hope for a new Nicaragua, where the full rights of citizenship and access to public goods would be accessible to all.

Two programs in particular, the national literacy campaign (more than half the population was illiterate in 1980) and a national campaign for basic public health (life expectancy of Nicaraguans in the 1970s was only 54 years old) formed the heart of the early Sandinista agenda. The posters here promote these Sandinista social programs, and, generally speaking, the Sandinista cause. They are part of a collection held in the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin. Their strong graphic qualities reflect both the aesthetics of the late 1970s and the Sandinistas’ need to convey political information visually to a largely unlettered citizenry.

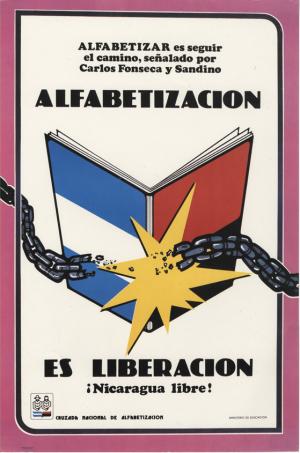

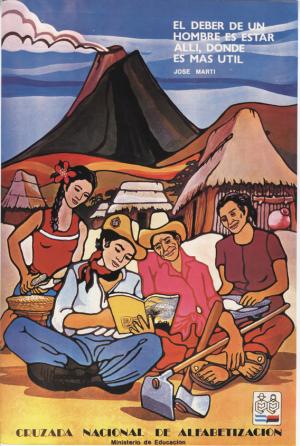

THE LITERACY CAMPAIGN

One of the first objectives of the revolution was to introduce basic literacy to Nicaragua’s large illiterate population, in order to both improve people’s lives and to inculcate them with the values of the Sandinista revolution. The National Literacy Crusade, headed by Fernando Cardenal, a Jesuit priest, sent “brigades” of young, urban Nicaraguans to remote parts of the country to teach basic literacy to adults. Many of the early-reader materials utilized explicitly political motifs. Whether or not new readers embraced those ideas, the literacy crusade dramatically improved rates of functional literacy in adults by teaching more than 400,000 Nicaraguans to read and write. The program also introduced the young, urban teachers—brigadistas—to the realities of the poor rural countryside, many for the first time.

The quote printed near the top of this poster, “The duty of a man is be where he is most needed,” comes from the great Cuban nationalist of the late 19th century, José Martí. In this drawing we can see the young brigadista—clearly identifiable not only by his red Sandinista kerchief and CNA hat, but also by the relative whiteness of his skin—sitting on the ground with a rural campesino (peasant) family and exploring a book that bears the hallmarks of the National Literacy Crusade (or CAN). We see that two of the campesinos are older adults, while a young woman also looks on. The campesinos are surrounded by the tools and implements used by ordinary workers—the man has a hoe and ax, while both women hold manos y matates—corn grinders for making tortillas—all common tools that signify the Sandinsitas’ desire to value to both literacy and labor. In the background are the humble, thatched-roof wattle-and-dab houses common in the Nicaraguan countryside, all in the shadow of a volcano, a geographic feature so characteristic of Nicaragua that it has been used as a signifier for the nation on stamps, coins, the national flag and the Nicaraguan Coat of Arms.

For more on the resources of the Nettie Lee Benson collection, see http://www.lib.utexas.edu/benson/

Further readings on Nicaragua in this period:

Michel Gobat. Confronting the American Dream: Nicaragua under U.S. Imperial Rule (Duke, 2005)

John A. Booth, The end and the beginning: the Nicaraguan Revolution (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1982)

John Donahue, The Nicaraguan revolution in health: from Somoza to the Sandinistas (South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey, 1986)

English translations of posters (by order of appearance):

“Childhood is happiness. Happiness is the revolution.” The Luis Alfonso Velazquez Association of Sandinista Children.

“The People and Army United Guarantee Victory. “(FSLN)

“The Motherland…the revolution.” Ministry of Public Education and Propaganda.

“Literacy is liberation. [To be literate] is to follow the road marked out by Carlos Fonseca (a founder of the FSLN who died in 1976) and Sandino. Free Nicaragua!” (National Literacy Crusade)

“The duty of a man is to be here, where he is most needed.” National Literacy Crusade..

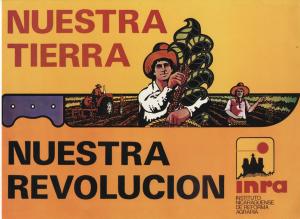

“Our Land: Our Revolution.” The Nicaraguan Institute of Agrarian Reform.