Ideas about race and eugenics have had a long influence on U.S. immigration and citizenship laws. A pair of historical exhibits ongoing in New York City vividly convey this troubling history. The regulations governing U.S. borders reveal the beliefs of legislators, but also many Americans, regarding what kinds of people are “fit to be citizens.” These two exhibits, “Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion” at the New York Historical Society and “Haunted Files: The Eugenics Records Office” at New York University, demonstrate how deeply entrenched such beliefs have been and the many forms of inequality that they produce and signify.

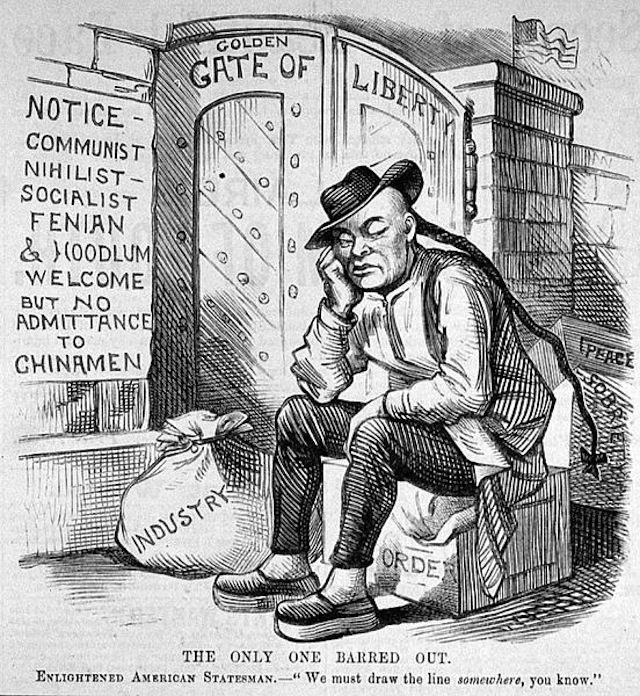

A political cartoon from 1882, showing a Chinese man being barred entry to the “Golden Gate of Liberty”. The caption reads, “We must draw the line somewhere, you know.” (Wikipedia)

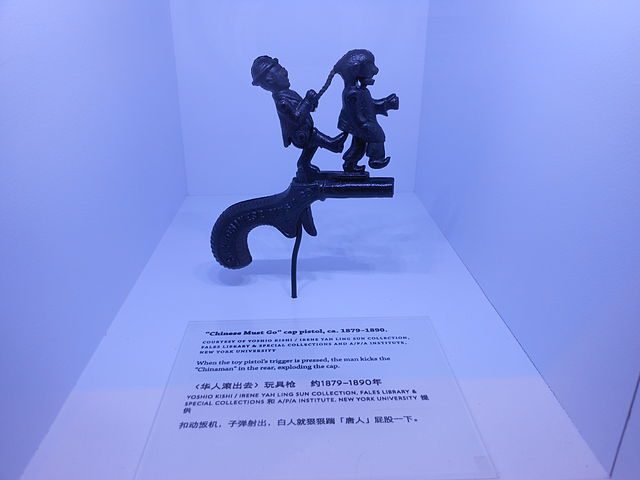

For example, in 1882 the United States set a precedent in making Chinese the first and only group identified by race for severely restricted entry rights into the United States and bars against their naturalization. The so-called Chinese Exclusion Law lay the foundations for future U.S. immigration laws that targeted an expanding array of undesirable people by race, national origin, illiteracy, imbecility, and likelihood to become a public charge. By 1924, a majority of the world’s people, originating everywhere from Palestine to Southeast Asia, could not legally enter the United States and eastern and southern Europeans faced much higher bars against entry than their counterparts from western and northern Europe.

The “science” of eugenics made such immigration controls seem to be a necessity for national preservation. As one slogan claimed: “Every 15 seconds $100 of your money goes for the care of persons with bad heredity,” thereby mandating the use of laws to protect U.S. population, civilization, and resources. Bolstered by protracted schemes to measure quantitatively, systematically categorize, and document racial and other inherited attributes, eugenics bore the force of natural selective processes, thereby tempting its practitioners to intervene in its principles in order to improve the caliber of American human beings. Such quests for a higher order of civilization and society irreparably marginalized and damaged humans identified as inferior by their ancestral traits.

In conjunction, “Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion” and “The Haunted Files” provoke insights regarding the very close relationships between U.S. immigration laws, our restrictions upon citizenship, and naturalized assumptions about what kinds of persons deserve to join America’s democracy.

Madeline Hsu’s book The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority is now available for pre-order from Princeton University Press.

More from our series of history museums:

NEP editor Joan Neuberger visits the Museum of Liverpool

You may also like:

Madeline Hsu’s article on Chinese Texans

UT Professor of History Philippa Levine on the global history of eugenics