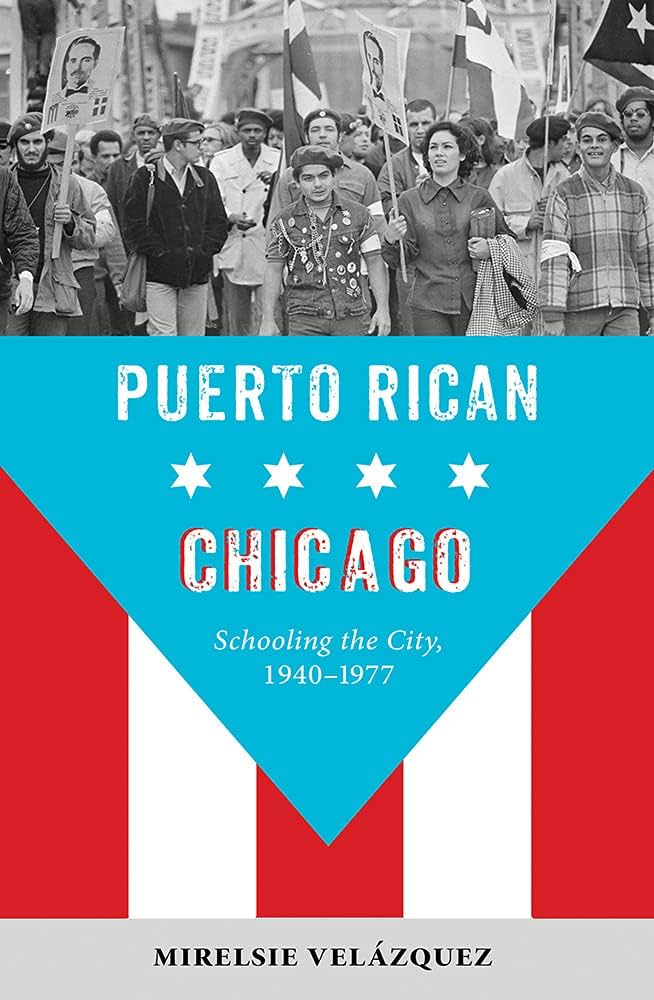

In Puerto Rican Chicago: Schooling the City 1940-1977, Mirelsie Velázquez provides an eye-opening account of Puerto Ricans’ relationship to colonialism and education as they migrated to the city of Chicago in the mid-twentieth century. The book presents a thorough examination of how these migrants built and fought for a community through the lens of K-12 and postsecondary education systems, showing how colonial education policies and principles followed Puerto Ricans in their schooling across the United States. It fits well within the literature of Latino education history, specifically involving civil rights, alongside books like Brown Not White: School Integration and the Chicano Movement in Houston by Guadalupe San Miguel Jr., while also providing an important contribution to the growing field of Latino studies in the Midwest, and it aims to bring public schools into the discussion as a transformative force in the region.

The book is shaped by the author’s experiences as a Puerto Rican woman who spent her formative years in Illinois and now teaches at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Velázquez states that intersectionality (the interconnectedness of different social categories which lead to discrimination) “of schools, oppression, and liberation” was a guiding influence for the diasporic Puerto Rican community and argues that its history cannot be separated from its relationship to colonialism (p.19). She uses this to analyze the intersection of concepts such as Coloniality of Power (the understanding of power structures that remain after decolonization) to diaspora studies as well as urban history, as the Puerto Rican communities she studies only formed in the large cities of New York and Chicago.

Puerto Rican Chicago is the product of archival and oral history methodology. Velázquez notes that a challenge she encountered was the silences in primary sources directly depicting Puerto Ricans during the early decades of their mass migration. This created gaps in the narrative “from the community’s own voices,” something she skillfully supplemented with oral interviews (p. 20). The strength of her use of the archives is found in her sources from the 1960s—discussed most heavily in chapter five—which delves into print media produced by and for Puerto Ricans in their own words. The methods she uses shape her argument that schools were an essential place of the community fighting against inequality by providing the personal reasons and motivations behind their actions.

The author emphasizes the connectedness of Puerto Rican civil rights movements in Chicago to other cities and movements by other groups, including African Americans and Chicanos. She depicts the Chicago community as intricately connected to New York City, both as a legacy of migration and an ongoing relationship that tied the two communities together through familial relations, organizations like the Young Lords, and print media. By placing her own findings within the context of existing literature on New York’s Puerto Rican communities and other civil rights movements, especially those where African Americans and Chicanos fought for their right to a just education, she further solidifies this connection.

Midway of Riverview Park, Chicago ca. 1950s-1960s. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Velázquez frames her study as an effort to center women and their activism, but the source material she draws on more often reveals the limits placed on women’s participation in community organizing, a limitation she herself acknowledges. For example, even Que Ondee Sola, a newspaper that she states was notable for its inclusion of women, did not include the depiction of women as part of its mission, nor were women “equally represented on the writing staff” (p. 149). This also remains true for the women depicted in the involvement of schools, who were exceptions to the rule rather than the norm. Her argument could have been strengthened by reframing her claim to emphasize that women’s involvement was silenced even by their contemporaries as it aligns more with the information she presents on women’s sidelining in their participation in community organizing and activism.

The book is organized into five chapters. Chapters One and Two discuss Puerto Ricans’ historical relationship with colonial schooling and argue that the school system in Chicago is a continuation of Americanizing practices. In both, she discusses that schools were a reflection of the community’s struggles with issues of adequate housing and labor. She also creates a cyclical narrative of how Puerto Ricans adjusted to the city, how the city responded to them, and how the group reacted to their systematic treatment. Chapters Three and Four focus on school systems, with the first depicting community involvement in K-12 public schools and the latter on universities. Velázquez stresses the importance of student involvement in both, as students and their communities fought for adequate services and against discriminatory practices. Chapter Five discusses Puerto Rican newspapers and journals in Chicago and across the country, which highlighted community voices and needs with varying degrees of radicality.

Paseo Boricua in Chicago. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As debates over education and immigration continue to shape American politics, understanding the fight for civil rights in the nation’s public schools remains essential. Puerto Rican Chicago is an important contribution to the intersection of education, immigration, and cultural history, all in the burgeoning field of Latinos in the Midwest. It is also a beautiful exploration of the strength of the Puerto Rican immigrant community building in the face of systemic oppression, which in their case uniquely stems from the United States in both their place of origin as citizens of a U.S. territory and their destination as migrants to Chicago. The book can easily find a home on immigration, Latino, and education history syllabi, as well as on the bookshelf of anyone who has faced their own experiences with the U.S. education system as part of a diaspora. As this book importantly reminds us, Americanization is something that is constantly occurring in U.S. schools, a continuing legacy of colonialism and empire. But it is not the unstoppable force that it strives to be.

Kara Alexandra Culp is a current history PhD student at UT Austin, focused on Latina/o history in the 20th-century United States. Her dissertation project aims to explore the effects of education policy and law on Latina/o immigrant students in the borderlands in the 1970s and beyond.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.