The world’s attention was captured in 2012 by the disaster that befell the Costa Concordia, a cruise ship that ran aground off the coast of Italy leading to 32 deaths.

This shipwreck is the most recent one covered in A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks, whose expansive gaze covers much of the world from 6000 BCE to the present. Like several other books containing the words “A History of the World in ..” in their title, Stewart Gordon’s work attempts to encapsulate world history through the close study of a set number of things. Other examples of this approach include A History of the World in 100 Weapons, A History of the World in 12 Maps, A History of the World in 6 Glasses, and the very successful A History of the World in 100 Objects, a collaborative project between BBC Radio and the British Museum. Focusing on a few cases as a way to illustrate global trends is both entertaining and effective – the reader can acquire interesting details about specific things and learn about the broader context at the same time.

Shipwrecks are dramatic occurrences that are often tragic for those involved, but they can also lead to the preservation of artifacts that can be studied and analyzed, sometimes centuries or millennia after the events themselves. The Bremen cog from German, considered the best surviving specimen of this type of vessel, sank in 1380 but was not discovered until 1962.

The cog was the dominant ship in northern Europe between about 1200 to 1450 CE. It was a bulk carrier of beer and wool and also served as a warship. Another ancient type of ship is the Khufu barge, featured in the second chapter of A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks. This boat was buried in the Great Pyramid of Giza around 2600 BCE and was not discovered until 1954. The Khufu barge, like several of the ships featured in the book, was not destroyed at sea but Gordon uses a broad definition of shipwreck because his chief goal is to examine the varieties of ships that have existed in human history and the maritime worlds they helped shape.

The shipwreck is therefore just an entry point for Gordon into the far larger topic of maritime history. Each shipwreck allows the author to understand the various ways ships influenced the human societies that utilized them. He explains how each type of vessel was built, the purposes to which it was put, its strengths and weaknesses as a ship, and the maritime network it created. He begins the book with the dugout canoe, a variety of boat found in several parts of the ancient world. The chapters then follow a chronological sequence from the dugout to the modern cruise ship with a variety of stops along the way, including the famous seventh-century Sutton Hoo burial, the Intan shipwreck from Indonesian waters, a Spanish galleon, an American clipper ship, and the Exxon Valdez.

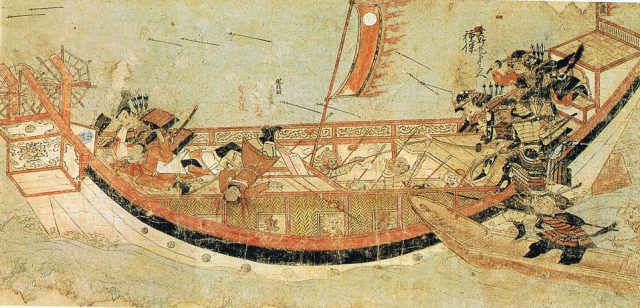

At times, Gordon uses literary evidence to launch his discussion, instead of an actual physical relic. His chapter on the Arab dhow that plied the waters of the western Indian Ocean, for instance, relies on twelfth-century letters preserved at a synagogue in Cairo. We learn about the Barbary war galley from the sixteenth-century memoir of an Englishman who described the ordeals of slavery that he faced after his ship was attacked and boarded in the Mediterranean. Another chapter covers the attempted invasion of Japan by the Mongol leader Khubilai Khan in the thirteenth century, known to us from many sources of information, including Japanese picture scrolls painted soon afterward. Above, we see Mongol warriors shooting arrows from a ship on the left hand side, while Japanese samurai board a Mongol ship on the right.

Although Gordon makes a concerted effort to examine ships from many areas of the world, the coverage shifts more and more to vessels from Europe and the United States as we get closer to the present. The case of the HMS Victory, sunk in a storm after breaking a blockade in the Mediterranean in 1744, sheds light on the rise of British naval power. The radical reduction of transport time resulting from use of the steam engine is illustrated by means of the Lucy Walker, a sidewheel steamboat that plied the waters of the Mississippi River. Its engines overheated and blew the boat apart one day in 1844, with at least 43 casualties resulting.

The horrible scene of this explosion, a common problem for steamboats, was depicted by an artist in 1856. The transporting of large numbers of people, rather than cargo, became the rationale for large passenger ships such as the Lusitania. Almost 1200 people died when it was struck by a torpedo from a German submarine in 1915, while en route from New York to Liverpool – a depiction of which adorns the cover of A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks.

Going well beyond the topic of shipwrecks, this enjoyable and educational book exposes the reader to diverse seascapes, social terrains, and political developments, as well as considerable information about trading patterns. In its geographic breadth and temporal length, it provides an admirable example of history writing on a world historical scale. Overall, A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks is an engaging introduction to maritime history that explores the impact of specific types of ships in their regional economies and the gradual emergence of a globally connected maritime world by the twentieth century.

Stewart Gordon, A History of the World in Sixteen Shipwrecks (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2015)

More by Cynthia Talbot on Not Even Past:

A History of the World in 100 Objects by Neil MacGregor (2011)

Great Books on Women’s History: Asia

You may also like:

Andres Lombana-Bermudez and Blake Scott discuss Colón 2000: Tour Guides, Cruiseships, and Tourists in Panama