by Edward Shore

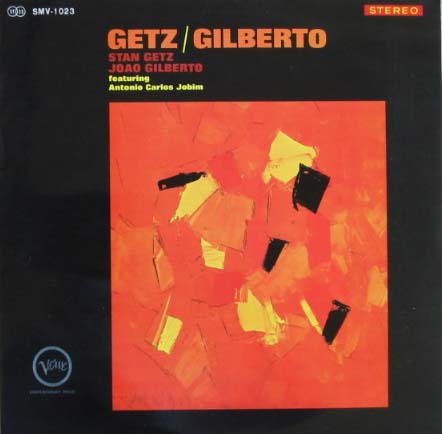

“I’m not a sociologist but it was a time when people in the States wanted to turn to something other than their troubles,” Brazilian singer Astrud Gilberto mused in 1996. “There was a feeling of dissatisfaction, possibly the hint of war to come, and people needed some romance, something dreamy for distraction.” This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of 1964’s Getz/Gilberto, the triumphant collaboration between North American jazz saxophonist Stanley Getz (1927-1991), Brazilian singer and guitarist João Gilberto (b. 1931), his then-wife, Astrud Gilberto (b. 1940), and their friend and compatriot, the composer Antonio Carlos “Tom” Jobim (1927-1994).

Getz/Gilberto was not North America’s first encounter with bossa nova, the lyrical fusion of samba and cool jazz emanating from the smoky nightclubs, recording studios, and performance halls of Rio de Janeiro in the mid-1950s. Yet the eight-track LP was by far the most successful. Propelled by the genre-defining single, “The Girl From Ipanema,” Getz/Gilberto spent ninety-six weeks on the charts and won four Grammy awards, including Best Album of the Year in 1965. Other tracks, including “Para Machucar Meu Coração,” “Desafinado,” and “Corcovado/Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars,” also became jazz standards. “Americans are generally not very curious about the styles of other countries,” Astrud Gilberto insisted. “But our music was Brazilian music in a modern form. It was very pretty and it was exceptional for managing to infiltrate America’s musical culture.”

Getz/Gilberto was not North America’s first encounter with bossa nova, the lyrical fusion of samba and cool jazz emanating from the smoky nightclubs, recording studios, and performance halls of Rio de Janeiro in the mid-1950s. Yet the eight-track LP was by far the most successful. Propelled by the genre-defining single, “The Girl From Ipanema,” Getz/Gilberto spent ninety-six weeks on the charts and won four Grammy awards, including Best Album of the Year in 1965. Other tracks, including “Para Machucar Meu Coração,” “Desafinado,” and “Corcovado/Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars,” also became jazz standards. “Americans are generally not very curious about the styles of other countries,” Astrud Gilberto insisted. “But our music was Brazilian music in a modern form. It was very pretty and it was exceptional for managing to infiltrate America’s musical culture.”

What explains Americans’ love affair with bossa nova in the winter of 1964? Part of the answer lies in the power of popular music to relieve a broken heart. Critics associated Getz/Gilberto’s cool, sophisticated sound with the Kennedy White House, where music, high fashion, and glamorous parties had been hallmarks of “Camelot” on Pennsylvania Avenue during the early 1960s. Perhaps audiences sought to recapture a bit of the mystique that had vanished when President Kennedy was slain in Dallas, Texas, only five months before the record’s release.

For jazz critic Howard Mandel, Getz/Gilberto was like “another tonic for the assassination’s disruption, akin for adults to the salve upbeat the Beatles had provided for teenagers’ after their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964.” Gilberto’s hushed vocals and understated guitar, Jobim’s gentle piano, and Getz’s lush saxophone transported weary listeners to a sun soaked, tropical paradise light years removed from the turmoil confronting the United States in the winter of 1964.

For jazz critic Howard Mandel, Getz/Gilberto was like “another tonic for the assassination’s disruption, akin for adults to the salve upbeat the Beatles had provided for teenagers’ after their appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964.” Gilberto’s hushed vocals and understated guitar, Jobim’s gentle piano, and Getz’s lush saxophone transported weary listeners to a sun soaked, tropical paradise light years removed from the turmoil confronting the United States in the winter of 1964.

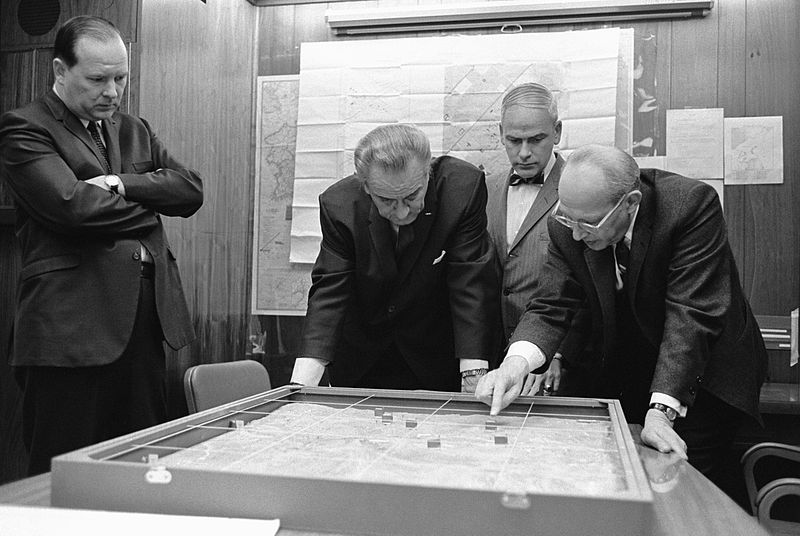

Yet the Brazil of North American fantasy–languid, exotic, and serene–contrasted sharply with reality. By late 1963, the United States had declared Brazil a “trouble spot” in its hemispheric crusade against communism. Traditional elites and U.S. Cold Warriors opposed Brazilian President João “Jango” Goulart and his center-left agenda, which extended voting rights to illiterates, taxed foreign corporations, and introduced land reform. Meanwhile, peasant agitation in the Brazilian Northeast, the fulcrum of the global sugar trade, deepened the anxieties of U.S. policymakers who feared that Latin America’s largest economy might soon follow in Cuba’s footsteps. In March 1964, the Lyndon Johnson administration and the Brazilian military secretly began plotting Goulart’s overthrow.

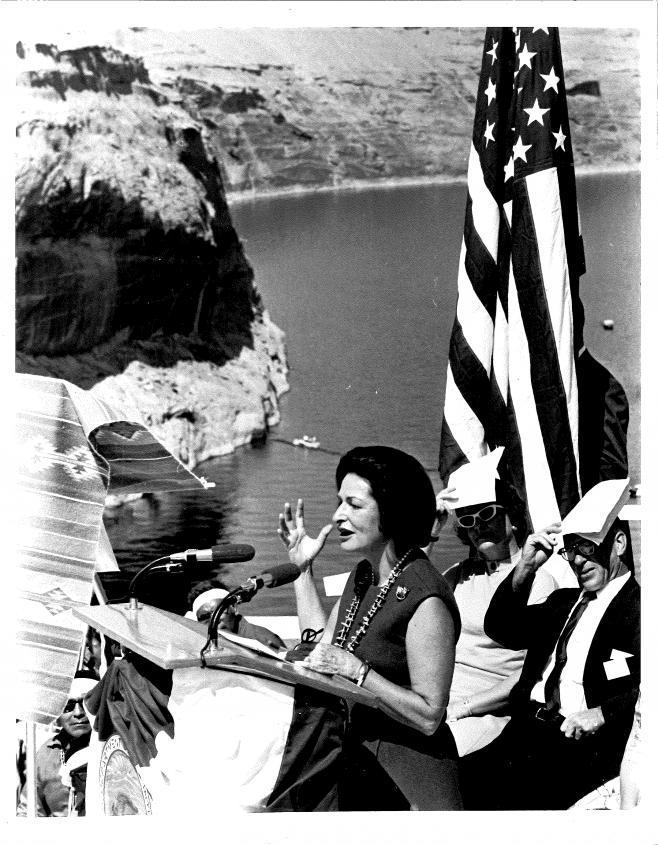

While “The Girl from Ipanema” climbed to the top of the Billboard charts, U.S. warships penetrated Brazilian waters to support a military coup d’état on April 1, 1964, terminating the country’s brief flirtation with social reform. The United States had once again intervened in Latin America to preserve an illusion of tropical tranquility that existed only in the imaginations of ruling elites, intelligence agencies, and North American consumers. The military dictators who succeeded Jango and controlled Brazil for the next two decades understood the uses of music just as well and embraced bossa nova for its commercial appeal, apolitical subject matter, and potential to smooth over the nation’s deep-seated socio-political divisions.

While “The Girl from Ipanema” climbed to the top of the Billboard charts, U.S. warships penetrated Brazilian waters to support a military coup d’état on April 1, 1964, terminating the country’s brief flirtation with social reform. The United States had once again intervened in Latin America to preserve an illusion of tropical tranquility that existed only in the imaginations of ruling elites, intelligence agencies, and North American consumers. The military dictators who succeeded Jango and controlled Brazil for the next two decades understood the uses of music just as well and embraced bossa nova for its commercial appeal, apolitical subject matter, and potential to smooth over the nation’s deep-seated socio-political divisions.

Yet the marriage between bossa nova and the dictatorship was not to last. A younger generation of Brazilian artists, including Caetano Veloso, Gal Costa, Gilberto Gil, Rita Lee, and Tom Zé, fused elements of bossa nova with rock n’roll, psychedelia, experimental theatre, and Brazilian folk music into the colorful, exuberant countercultural movement known as Tropicália. Gone was the “tall, tan, young, and lovely” morena of Ipanema Beach. By 1968, the regime’s censors raced to cleanse Brazilian popular music of anti-establishment themes, even forcing Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, two of the country’s most visible stars, into exile in the United Kingdom. The coup government ultimately turned its back on bossa nova, too. In 1969, the regime sacked Vinícius de Moraes from his post in the Foreign Ministry after the legendary composer, playwright, and original author of “The Girl from Ipanema” criticized the dictatorship’s restraints on artistic freedom.

Popular interest in bossa nova continued to wane over the course of the 1970s. Outraged by U.S. sponsorship of the military regime, Brazilian musicians distanced themselves from a style that enjoyed intimate ties to the “giant from the North.” A blend of rock, samba, and jazz known as MPB, or “música popular brasileira,”eclipsed bossa nova as Brazil’s national sound. MPB artists like Chico Buarque, Jorge Ben, and Novos Baianos camouflaged criticisms of government repression, social injustice, and imperialism with irresistible melodies, appealing to a growing audience of middle-class youth. Meanwhile, in the slums and favelas of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Salvador, a young generation of Afro-Brazilians challenged the nation’s vaunted reputation as a “racial democracy,” while embracing cultural symbols of Black Power and the African Diaspora, including soul, funk, and reggae. Amid this rising tide of popular protest against the regime, bossa nova, with its dreamy, cool detachment, appeared painfully at odds with the struggles of ordinary Brazilians.

Popular interest in bossa nova continued to wane over the course of the 1970s. Outraged by U.S. sponsorship of the military regime, Brazilian musicians distanced themselves from a style that enjoyed intimate ties to the “giant from the North.” A blend of rock, samba, and jazz known as MPB, or “música popular brasileira,”eclipsed bossa nova as Brazil’s national sound. MPB artists like Chico Buarque, Jorge Ben, and Novos Baianos camouflaged criticisms of government repression, social injustice, and imperialism with irresistible melodies, appealing to a growing audience of middle-class youth. Meanwhile, in the slums and favelas of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Salvador, a young generation of Afro-Brazilians challenged the nation’s vaunted reputation as a “racial democracy,” while embracing cultural symbols of Black Power and the African Diaspora, including soul, funk, and reggae. Amid this rising tide of popular protest against the regime, bossa nova, with its dreamy, cool detachment, appeared painfully at odds with the struggles of ordinary Brazilians.

Still, the genre remains a major force in Brazilian pop culture and “world” music. The millions of tourists who visit Rio de Janeiro every year arrive at an airport named after Tom Jobim. Inevitably, more than a few vacationers board their flights home in “Girl from Ipanema” t-shirts purchased at the airport gift shop. Bossa nova also experienced a brief resurgence in the mid-1990s. Red Hot+Rio, a compilation album produced by the AIDS-awareness organization Red Hot in 1996, paid tribute to the musical career of Tom Jobim and featured covers by artists including Sting, Astrud Gilberto, and David Byrne. Today, pop stars like Marisa Monte, Celso Fonseca, and Uruguay’s Jorge Drexler refashion bossa nova sounds for contemporary audiences. And what about the song that made bossa nova an international sensation? “The Girl From Ipanema” currently ranks as the second-most-recorded pop song of all time, after the Beatles’ “Yesterday.” Amid the pageantry surrounding the upcoming FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Rio Olympic Games, look for “The Girl From Ipanema” to sway gently back into the spotlight.

Stan Getz and Astrud Gilberto perform “The Girl From Ipanema” in 1964:

Hear more Bossa Nova:

João Gilberto and Antonio Carlos Jobim in a 1992 live concert

Elis Regina and Tom Jobim performing “Aguas de Março” in 1974

Astrud Gilberto’s comments can be found in “Interview with Astrud Gilberto,” by Howard Mandel, Verve Records, Re-issue of Getz/Gilberto, 1996, liner notes.

Howard Mandel’s comments come from correspondence with the author, January 2014. A special thanks to him from the author.

Photo Credits:

1964 LP cover of Getz/Gilberto (Image courtesy of Verve Records)

Creed Taylor, Antonio Carlos “Tom” Jobim, João Gilberto and Stan Getz recording together (Image courtesy of last.fm)

Brazilians marching against the country’s military dictatorship, 1964 (Image courtesy of Mount Holyoke College)

Musical team on Getz/Gilberto: (from left) Stan Getz, Milton Banana, Tom Creed Taylor, João Gilberto and Astrud Gilberto (Image courtesy of last.fm)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines