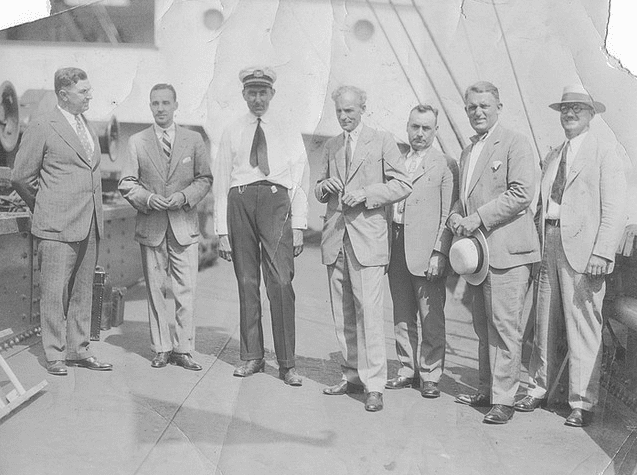

Greg Grandin has written a page-turner that tells the story of Henry Ford’s foray into the Brazilian Amazon and much more. In 1925, Ford met with Harvey Firestone to discuss England’s challenge to the US rubber supply. Much as the Belgians had done in Africa in the late nineteenth-century, England had extracted this resource by proxy—through companies such as the Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company in the Amazon and its Asian colonies. Ford’s response was to embark upon his own South American venture into the world of rubber.

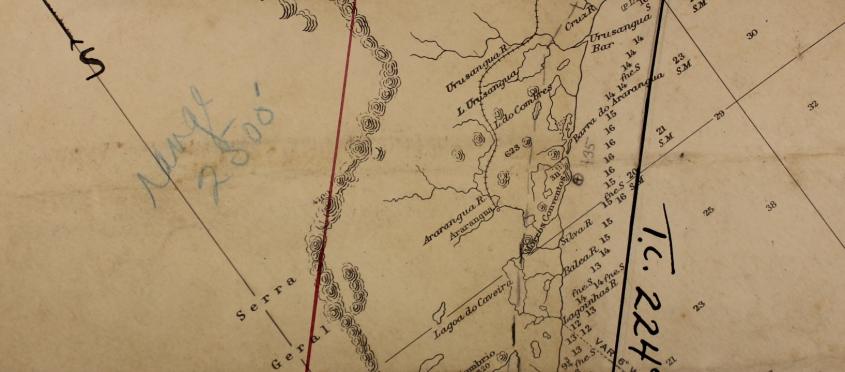

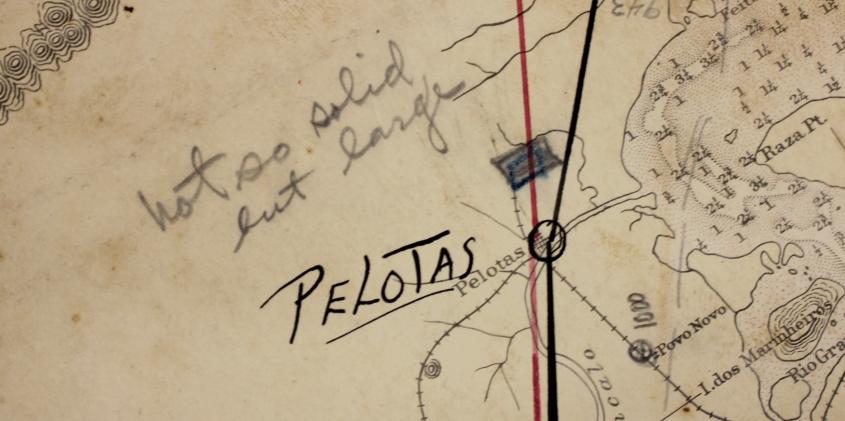

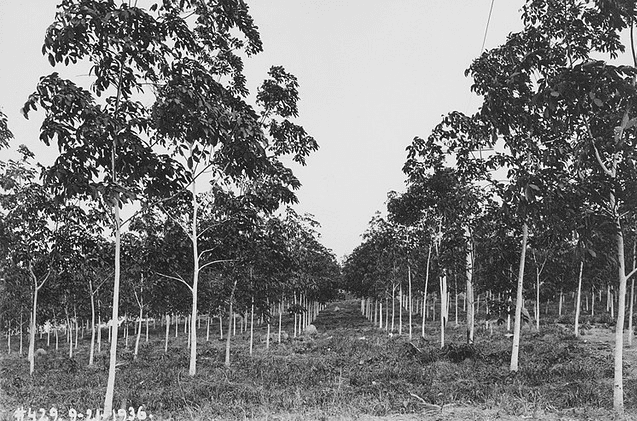

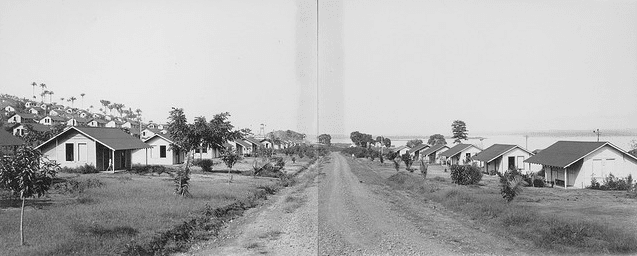

That same year, the governor of Pará sent Custódio Alves de Lima, a Brazilian diplomat, traveled to the U.S. with the aim of enticing Ford into establishing a rubber plantation in the region. The governor was prepared to grant Ford a number of perquisites, including land and tax concessions. Henry Ford took the bait. Within two years, he received a concession of close to 2.5 million acres, half private property at a cost of $125,000 and half public property granted to him free of charge. This tract of land that would soon be called “Fordlandia” became more than just a potential rubber plantation. Ford saw it as an opportunity to begin a new socio-industrial experiment that sought to impose his brand of Americanism on a people and environment.

That same year, the governor of Pará sent Custódio Alves de Lima, a Brazilian diplomat, traveled to the U.S. with the aim of enticing Ford into establishing a rubber plantation in the region. The governor was prepared to grant Ford a number of perquisites, including land and tax concessions. Henry Ford took the bait. Within two years, he received a concession of close to 2.5 million acres, half private property at a cost of $125,000 and half public property granted to him free of charge. This tract of land that would soon be called “Fordlandia” became more than just a potential rubber plantation. Ford saw it as an opportunity to begin a new socio-industrial experiment that sought to impose his brand of Americanism on a people and environment.

Over the next few decades, Ford’s determination to build a place that would “safeguard rural virtues and remedy urban ills” would meet its match in the Amazon. Ford’s emissaries began a Sisyphean attempt to clear land during the rainy season, they siphoned money to line their own pockets, and they began exploiting workers who were already leery of working on Ford’s jungle experiment. Workers were expected to work in extremely high heat and humidity. Adverse work conditions, coupled with an ignorance of Amazonian epidemiology, led to many deaths. Such a high rate of mortality at Ford’s Amazon project was a common feature of other U.S. and European forays into Central and South America in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In The Path Between the Seas, for instance, David McCullough tells the story of how the building of the Panama Canal, which at various points in its history was in the hands of a Frenchman and an American who each refused to give up in the face of nature’s challenges, also resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of workers from disease and various threats of the Panamanian jungle.

Over the next few decades, Ford’s determination to build a place that would “safeguard rural virtues and remedy urban ills” would meet its match in the Amazon. Ford’s emissaries began a Sisyphean attempt to clear land during the rainy season, they siphoned money to line their own pockets, and they began exploiting workers who were already leery of working on Ford’s jungle experiment. Workers were expected to work in extremely high heat and humidity. Adverse work conditions, coupled with an ignorance of Amazonian epidemiology, led to many deaths. Such a high rate of mortality at Ford’s Amazon project was a common feature of other U.S. and European forays into Central and South America in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. In The Path Between the Seas, for instance, David McCullough tells the story of how the building of the Panama Canal, which at various points in its history was in the hands of a Frenchman and an American who each refused to give up in the face of nature’s challenges, also resulted in the deaths of tens of thousands of workers from disease and various threats of the Panamanian jungle.

Ford also tried to impose a lifestyle that did not jibe well with Fordlandia workers. His attempt at cultural imperialism met violent resistance, such as a multi-day riot that started in the worker’s dining hall. Up until the riot, the men had often taken their meals at local brothels and saloons. Ford, who was a teetotaler, implemented a new policy to coerce the men into eating their meals at the mess hall instead. Money for meals was automatically deducted from their paychecks and the workers resented this. To make matters worse, Ford managers chose a bland menu: oatmeal, canned peaches, and unpolished rice. The mess hall riot signaled the beginning of the end of Ford’s project aimed at restoring a bygone era. By 1945, Fordlandia had failed.

Ford also tried to impose a lifestyle that did not jibe well with Fordlandia workers. His attempt at cultural imperialism met violent resistance, such as a multi-day riot that started in the worker’s dining hall. Up until the riot, the men had often taken their meals at local brothels and saloons. Ford, who was a teetotaler, implemented a new policy to coerce the men into eating their meals at the mess hall instead. Money for meals was automatically deducted from their paychecks and the workers resented this. To make matters worse, Ford managers chose a bland menu: oatmeal, canned peaches, and unpolished rice. The mess hall riot signaled the beginning of the end of Ford’s project aimed at restoring a bygone era. By 1945, Fordlandia had failed.

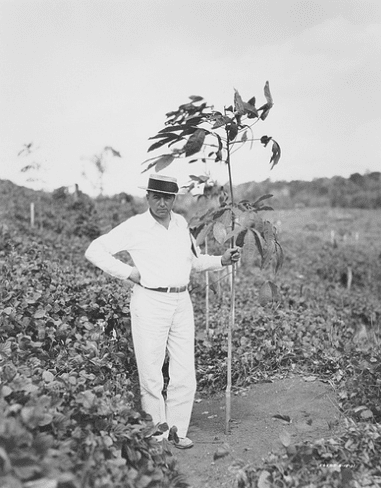

Grandin is ambivalent about explaining this failure as rooted in Ford’s hubris, opting instead for the negative effects of deindustrialization. Much of the evidence, however, points to Ford’s excessive self-confidence as a primary factor for the failure of his Amazonian project. To begin with, he purposely did not hire experts—botanists, agronomists, interpreters—who could have helped Fordlandia succeed. The Amazon was not the only place where Ford’s personal hang-ups, like his suspicion of experts and his cantankerousness, caused problems. Grandin transports readers back and forth between Brazil and the U.S. to show that at the same time that Ford was trying to build a perfect world in the middle of the jungle, his empire at home was beginning to show the strain of scandals and shop-floor abuses of despotic foremen in his factory.

Grandin is ambivalent about explaining this failure as rooted in Ford’s hubris, opting instead for the negative effects of deindustrialization. Much of the evidence, however, points to Ford’s excessive self-confidence as a primary factor for the failure of his Amazonian project. To begin with, he purposely did not hire experts—botanists, agronomists, interpreters—who could have helped Fordlandia succeed. The Amazon was not the only place where Ford’s personal hang-ups, like his suspicion of experts and his cantankerousness, caused problems. Grandin transports readers back and forth between Brazil and the U.S. to show that at the same time that Ford was trying to build a perfect world in the middle of the jungle, his empire at home was beginning to show the strain of scandals and shop-floor abuses of despotic foremen in his factory.

In typical Grandin style, the book ends in the contemporary period. Today the Amazon forest suffers from rapid deforestation caused in part by projects like Ford’s. His doggedness in growing rubber trees his own way led Ford to clear acres upon acres of forest. Soy farming, another of Ford’s projects, required the use of toxic chemicals that have allowed this non-native crop to thrive by killing off native species. The environmental degradation that modern industry and agriculture cause is not often something that consumers consider when they purchase a car that has Brazilian soy-based plastic parts or purchase a piece of furniture containing particle board made from young trees that could have reforested the Amazon if they had been left to mature. This disjuncture between the environmental and human degradation associated with mass production and consumption is characteristic of far too-many commodity chains.

In typical Grandin style, the book ends in the contemporary period. Today the Amazon forest suffers from rapid deforestation caused in part by projects like Ford’s. His doggedness in growing rubber trees his own way led Ford to clear acres upon acres of forest. Soy farming, another of Ford’s projects, required the use of toxic chemicals that have allowed this non-native crop to thrive by killing off native species. The environmental degradation that modern industry and agriculture cause is not often something that consumers consider when they purchase a car that has Brazilian soy-based plastic parts or purchase a piece of furniture containing particle board made from young trees that could have reforested the Amazon if they had been left to mature. This disjuncture between the environmental and human degradation associated with mass production and consumption is characteristic of far too-many commodity chains.

If Fordlandia is a story about one man’s attempt to impose his will over nature, it is also a story about modernity and globalization. While Grandin mentions only superficially the presence of women, Chinese, U.S. Confederates, and West Indian workers in the Amazon, readers can be sure that their presence was an effect of the shortening of time and space brought on by modernity that facilitated increased movement of people, goods, and ideas. In contrast to works that exalt the benefits of the modern world—in the realm of ideas and technological advancements, for instance—Grandin implies a weighty question. Has global industrial capitalism, of which Fordlandia is a microcosmic case-in-point, actually advanced humanity or are we now in an age of what scholars have called “the coloniality of power” where all of the old imperial modes are as entrenched as they were in the none too distant past, but now sporting the sheen of the twenty-first century?

If Fordlandia is a story about one man’s attempt to impose his will over nature, it is also a story about modernity and globalization. While Grandin mentions only superficially the presence of women, Chinese, U.S. Confederates, and West Indian workers in the Amazon, readers can be sure that their presence was an effect of the shortening of time and space brought on by modernity that facilitated increased movement of people, goods, and ideas. In contrast to works that exalt the benefits of the modern world—in the realm of ideas and technological advancements, for instance—Grandin implies a weighty question. Has global industrial capitalism, of which Fordlandia is a microcosmic case-in-point, actually advanced humanity or are we now in an age of what scholars have called “the coloniality of power” where all of the old imperial modes are as entrenched as they were in the none too distant past, but now sporting the sheen of the twenty-first century?

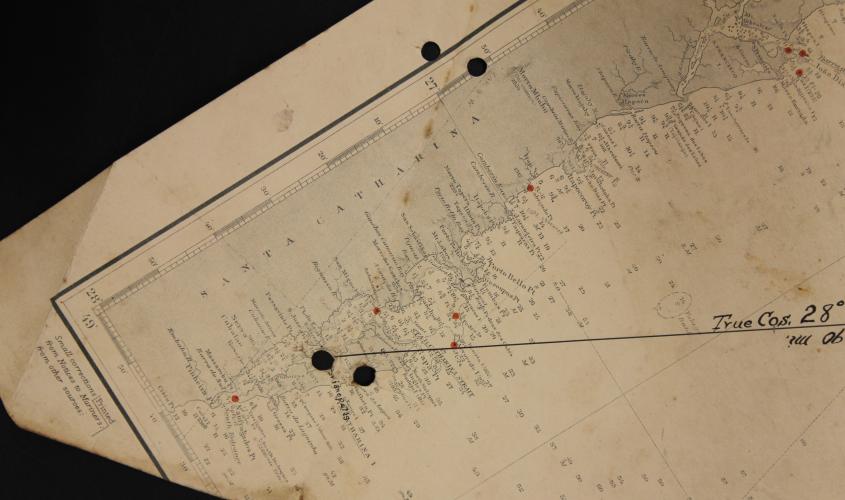

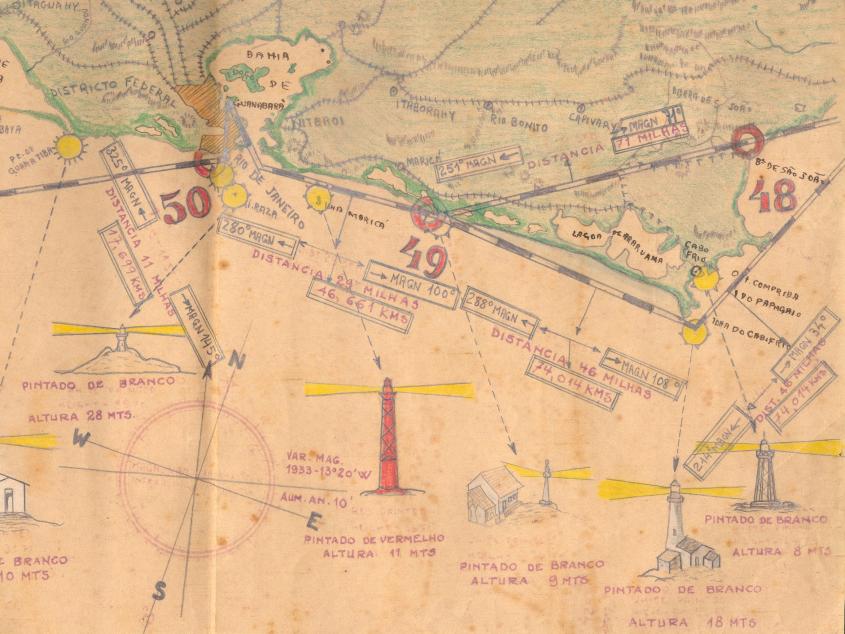

Photo credits:

All images courtesy of thehenryford/Flickr Creative Commons.