What does a Catholic Cardinal sequestered in the US embassy in Budapest and the dead body of an American found in Prague’s Vltava River in the 1960s have in common? Characters in a true crime podcast? No, at least not yet. Instead, these are examples of lives (and lives lost) whose stories are buried in the voluminous files of the Lyndon B. Johnson Library on the University of Texas campus. In addition to a fantastic museum, the Library contains an extensive archive of over 45 million pages of documents from the LBJ administration, providing a unique insight into America’s global reach during the momentous 1960s. For those who don’t have time to visit the wonderfully Cold War modern building and its peaceful reading room, there is also a considerable digital collection. Substantial as it may be, at last count, the percentage of digitized material was still well under 1%, a figure that is understandable given the scope of the collection and the resources required to scan and process materials for public online access. I experienced firsthand these challenges when I initiated and managed Cold War Chronicles, a decade-long (and ongoing) digitization project of the LBJ materials related to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe.

The Cold War is best studied and researched as a deeply transnational phenomenon, in which both sides were constantly observing and directly or indirectly engaging the other side. If we study Eastern Europe only from its own sources, we miss half of the conversation. With that in mind, I began to explore the vast collections housed in the LBJ library over 15 years ago, mining it for documents related to my own research on Cold War-era Eastern Europe. I recall, for example, researching US-Eastern Bloc competition and engagement at Cold War trade fairs as part of my broader interest in consumption practices and patterns under socialism. I found a fascinating memo written by Anthony Solomon, LBJ’s influential financial policy advisor, who pushed for increased trade with the Bloc at a time when many Americans opposed it: “It is clear to me that it is in our best interest to take actions which help bring about a diversion of their resources from military and space programs to consumer goods…Who among us wouldn’t rather have Soviet workers making passenger cars instead of missiles?”[1] Solomon seemed delighted by the idea of the Soviet citizens having to deal with traffic, parking issues, and their kids asking for the keys to the car. Indeed, new exchanges that exposed Eastern Bloc citizens to American consumer culture mushroomed under the LBJ administration, which led the Eastern Bloc to try (and fail) to “keep up.” I integrated this and other discoveries into my research as well as teaching on Cold War Eastern Europe, which foregrounds the permeability of the Iron Curtain, but also the East-West mutual preoccupations.

My research discoveries coincided with my assuming a new role as Director of the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (CREEES) in 2010. As director of CREEES, I had the pleasure of hosting and interacting with visiting scholars from Russia and Eastern Europe, many of whom were fascinated with the LBJ materials related to the former Eastern Bloc (and ex-Yugoslavia). These materials were cataloged in a rough guide created in 2009, which I still regularly consult. In 2014, I faced the daunting task of applying for a US Department of Education grant that would give CREEES the status of a National Resource Center (NRC). In preparing our proposal, we needed to think creatively about projects that would utilize the resources of UT relevant to the Eastern Bloc and ideally make them accessible to a much broader audience. We consulted with LBJ library archivists, who informed us that the repository’s documents are in the public domain, allowing us to digitize and post them on our site as desired. An LBJ documents digitization project was featured in our successful grant proposal, which gave CREEES the status of a National Resource Center (NRC) from 2014-2018, and again in 2018-22, and 2022-2026. The Cold War Chronicles project slowly but surely came to fruition.

Okay, but where to begin? The files related to the former Eastern Bloc were significant, and most of them were scattered among disparate collections, including those of Foreign Policy advisors like McGeorge Bundy and Walt Rostow, as well as collections on agriculture, trade, space, etc. There were also communications from heads of state, White House central files, and the list goes on. In the very beginning of the guide, however, there was an easy answer – the Country Files of the National Security collection. Given the concentrated nature of this set of documents, it made sense for us to digitize whole folders and boxes on each country of interest, as opposed to cherry-picking documents of interest. Thus, the online collection would be complete, allowing users to have a similar experience to being in the archive. Federal funds supplemented UT resources, which supported a (revolving) team of UT students and staff at CREEES and the UT libraries to scan, crop, tag, process, and post in Texas Scholar Works. By far the largest of these country collections was the USSR, with 15 boxes full of some 10,000 documents! Due to its sheer size, we decided to complete that collection last. As of fall 2025, it is still not available for public use, but it will be soon!

Instead, we started with Czechoslovakia, the largest and most significant of the Eastern Europe collections, because of the notable 1968 event, the so-called “Prague Spring” in which state reform snowballed into a popular movement for change to “socialism with a human face.” The result was a Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion of the country to crush the liberalized regime and its enthusiastic population. Indeed, our first iteration of a public website was on the Scalar platform, entitled “The Prague Spring Archive,” put together by Ian Goodale, who is currently the European Studies Librarian for the University of Texas Libraries. The LBJ documents shed light on day-by-day developments on the ground, the decision-making process around the US response, and the global reaction to this consequential set of events as the “Czechoslovak crisis.”

The Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. Source: Wikimedia Commons

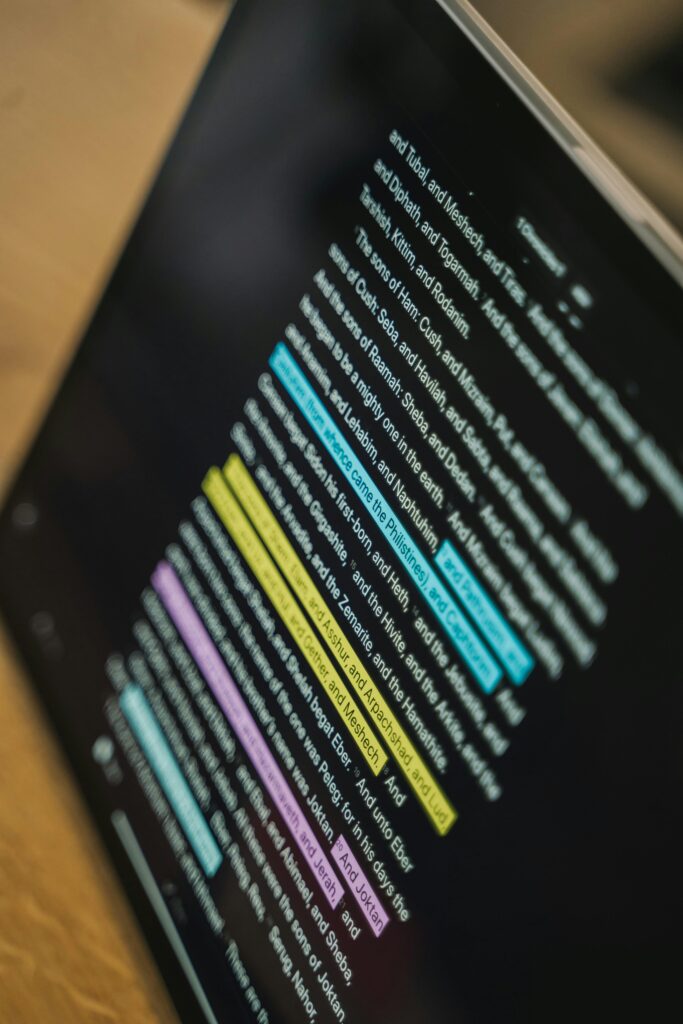

After Czechoslovakia, we went country by country across the region–Yugoslavia, Romania, Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, and finally the USSR and East Germany. As of fall 2025, most country files have been digitized, and only the Soviet and East German files remain to be fully processed and posted online. The cache of digitized documents is permanently housed in the Texas Scholar Works (TSW) repository, a massive open-access collection of materials that UT faculty and students have authored, digitized, or collected. In addition to its ample storage capacity, the repository provides convenient features for its collection, such as author and date searchability. However, its interface is not particularly flexible or user-friendly, and it does not allow for any curation of our collection. For that reason, I spearheaded the new Cold War Chronicles website, which we launched this fall in collaboration with a team of CREEES staff and students.

Cold War Chronicles offers a user-friendly portal and guide to our entire TSW collection, designed for researchers, teachers, or enthusiasts of Cold War history. For researchers, we provide a detailed guide with clear instructions on the scope of the collection and how to navigate, access, and cite the documents. The site also includes country-specific landing pages with general overviews of the sub-collection contents and links to folder-by-folder descriptions. I have also included a link to other English-language online archives for Cold War research, with direct links to search pages and short notes on navigation in cases where usability is not intuitive.

These other archives are also linked to through the “teaching resource” page, which includes a series of assignments that I created while teaching my “Cold War Eastern Europe” course at UT in spring 2025 (note: the Soviet Union was not a focus of the course, and the materials reflect that). In these assignments, students are asked to work in “country” groups on in-class activities that require them to dig into various online archives to find answers to prompts on discrete phases in the Cold War. The teaching resources also include a link to a list of English-language memoirs related to communist Eastern Europe and a sample assignment for using them in a course. These teaching materials are flexible and appropriate for higher education, as well as high school curricula.

Returning to the Catholic Cardinal stuck in the Budapest embassy, one of the most interesting collections of country files in our archive is Hungary. The Hungarian Cardinal Josef Mindszenty, designated “venerable” by Pope Francis in 2019, is a famous and revered figure in Hungary today. He spoke truth to power against Fascism and Communism, and as a result was imprisoned by both wartime and postwar regimes in Hungary. Released from prison during the famous Hungarian Revolution of 1956 against Soviet domination, he took refuge in the US embassy when the Soviet tanks rolled into Budapest and remained there until 1971! During the LBJ years, he wrote frequent letters, such as the one to LBJ, who responded through the local chargé d’affaires. The complete set of letters offers a rich Cold War chronicle of this episode in history, in which the US was harboring an enemy of the state in Hungary while trying to broker detente with the Eastern Bloc.

Cardinal József Mindszenty, 1956. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As far as the body in the Vltava River, it was Charles E. Jordan, executive vice president for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), who was found on August 20, 1967. Jordan was reported missing five days prior while vacationing in Prague, a side trip from his JDC work in neighboring Romania. Although it was reported as a suicide by Czech authorities at the time, there has long been speculation as to the cause of death, and it is considered an unsolved murder by the JDC.

Stories such as Mindszenty’s and Jordan’s are just a select few that were once buried among the millions of documents in the carefully kept boxes under lock and key in the LBJ Library. Now, at least some of these chronicles are online for all to access, although there is so much more to discover for those who can make it to the nearly windless white tower perched on a hill on the east end of our campus. Cold War Chronicles will continue to evolve over the coming years. This has truly been a labor of love for me and the CREEES team, and we sincerely hope teachers and researchers make use of this unique collection!

[1] Personal Papers of Anthony M. Solomon, East–West Trade, Box 1, file 1, p. 36. Lyndon Baines Johnson Library.

Mary Neuberger is the Mildred Hajek Vacek and John Roman Vacek Distinguished University Chair in Russian and Slavic Languages; Director of CREEES; and Chair of the Slavic & Eurasian Studies Department at UT Austin. Her research interests include urban culture, consumption, commodity exchange, and the history of truth at the intersection of science and religion in modern Eastern Europe, with a specialization in southeastern Europe.