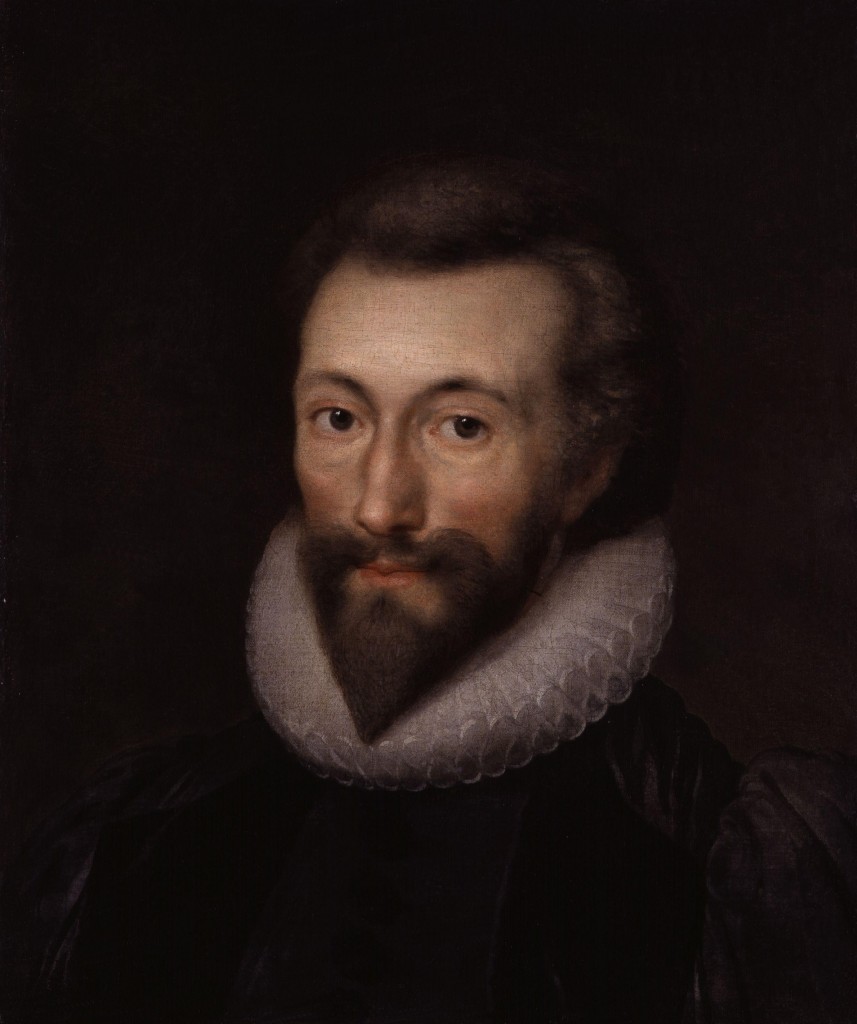

Ever wish you were actually there to experience a moment in history? What would it have been like to witness British soldiers marching into Concord? Or to hear the German bombers flying over London? The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project believes it can provide that very sensation—or at least approximate it. A group of historians, architects, and sound experts collaborated to digitally reconstruct the sights and sounds of a unique historical moment: London’s St Paul’s Cathedral on November 5, 1622, the 17th anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot by English Catholics to blow up Parliament. Through the power of computer technology, we are present as John Donne—one of England’s most renowned poetic voices—commemorates this traumatic event with a sermon paying tribute to God and King James I.

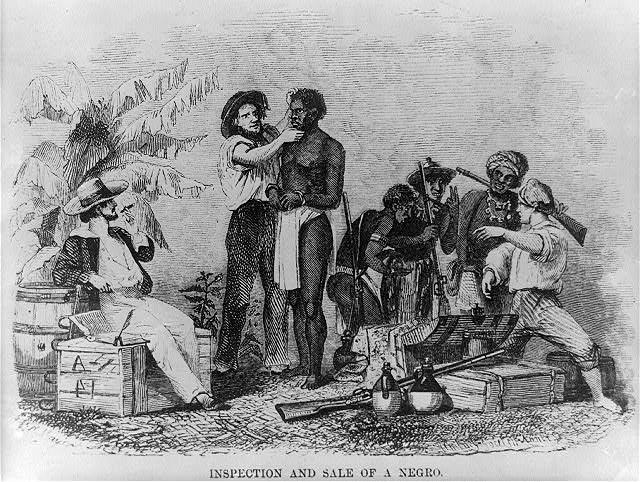

John Gipkin’s “Painting of Paul’s Cross,” 1616 (the Bridgeman Art Library, New York, and the Society of Antiquaries, London)

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project starts by digitally recreating St Paul’s Cathedral as it appeared in late 1622. According to one contemporary account quoted on the site, this was a place of great religious, civil, and social importance: a public space where “principal gentry, lords, courtiers, and men of all professions” converged. With the help of Google SketchUp, engineers were able to generate a 360-degree model of that very churchyard, its Romanesque cathedral, and the buildings surrounding it. But it does far more than just depict the physical space—it captures a particular moment in time. You can see the late fall’s dim light and low sun, the smoke rings filling the air from nearby chimneys, even the black birds circling overhead. What emerges is a detailed portrait of the space, the people present, and all the other bits of daily minutia so often lost to historians, yet so critical to shaping the feel of living in a place.

The site takes primary accounts of Donne’s speech, the crowd, and even the weather conditions of that November morning and brings them back to life. Users can actually watch computer generated reenactments of the speech—digital renderings of what scholars believe it looked like and sounded like to be in that churchyard as John Donne spoke. In order to faithfully reconstruct the crowd’s auditory experience, sound engineers considered a variety of factors, ranging from Donne’s speaking ability to the acoustic reverberations adjacent buildings likely produced. The reenactments even incorporate a variety of “pre-industrial” sounds that would have been echoing around the London churchyard in 1622. As Donne speaks, you can hear dogs barking, horses trotting, and workmen banging hammers.

The site includes not one, but a variety of video clips, each capturing how the sermon would have sounded from different vantage points. Class differences are even registered. While the distinguished guests sitting above in Sermon House would have clearly received the speech as it echoed through the house walls, more ordinary Londoners at ground level would have heard ambient street noise, chattering people, and crowing animals competing with Donne’s fainter, more distant words. Users discover that the listener’s unique position—both in terms of geography and social rank—created a unique aural experience.

The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project transforms the text of a speech into a dynamic performance of religious, political, and social meaning. Users can approximate the experience of history unfolding in real time by using more of their senses: listening and looking, and locating themselves in a virtual space. By reenacting the varied sounds of November 5, 1622, this multi-sensory project illuminates the varied social experience of seventeenth-century England. Despite the pageantry and ceremony surrounding it, Donne’s sermon was nothing more than background noise or a few snatched phrases to many ordinary Londoners. The Virtual Paul’s Cross Project elegantly reminds us that there is no one way to hear, see or understand a historical event. It all depends on where you’re sitting.

Watch a portion of the reconstructed sermon from the courtyard:

Or watch it from the Sermon House:

Catch up on the latest from the New Archive:

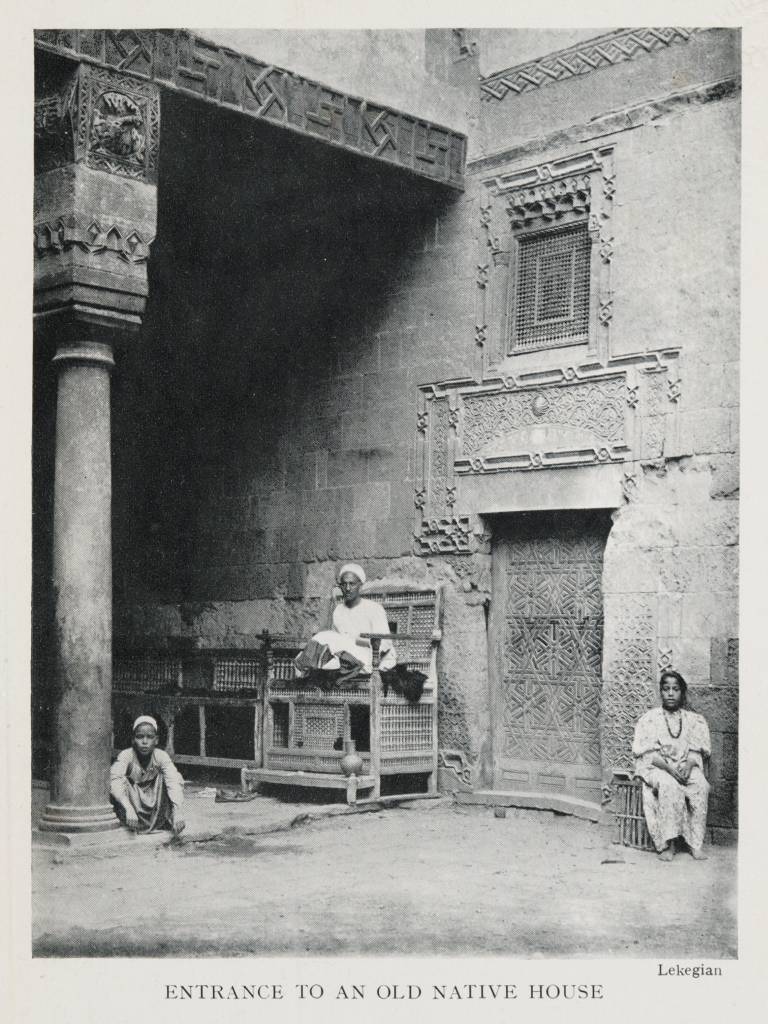

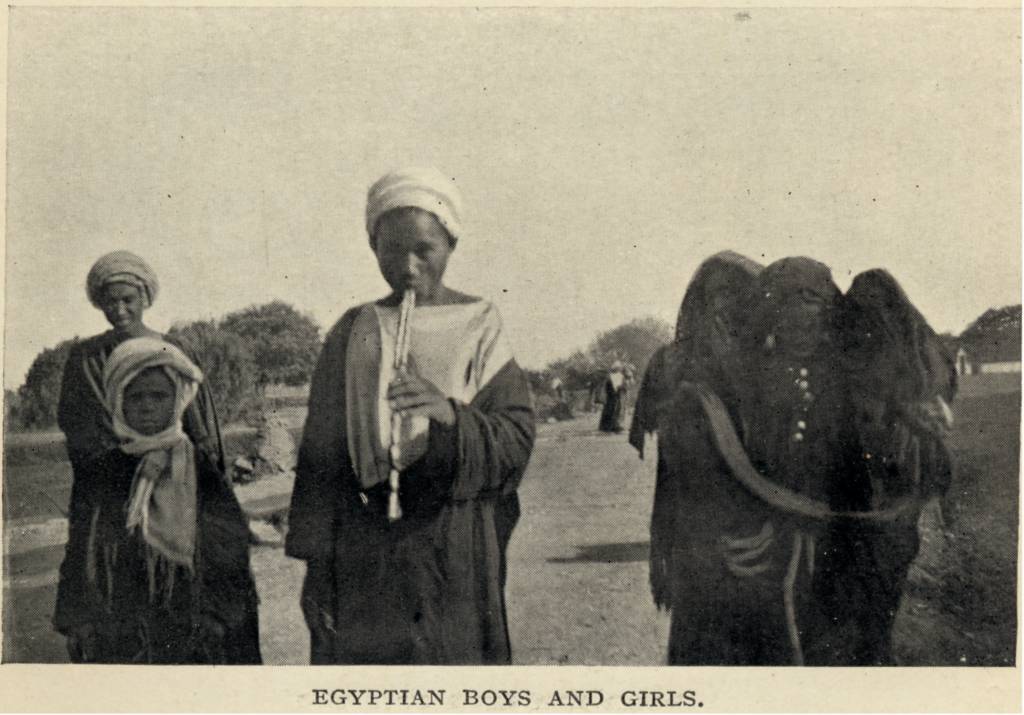

Victorian tourists exploring the people and places of Egypt

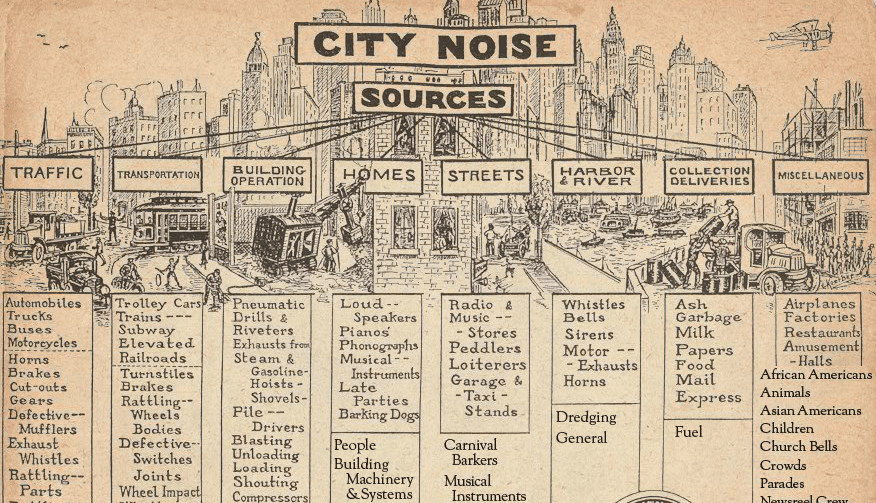

And a website that lets users hear 1920s New York City