Adam Curtis, Can’t Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World (BBC, 2021, 7 hours in 6 parts).

Meet Adam Curtis. Age: 66. Gender: Male. Race: White. Place of Birth: Dartford, UK. Marital Status: Unknown. Education: Oxford. Profession: Well . . . , here is where things get a bit complicated. Originally, Curtis saw himself as a historian, but for reasons that will soon become apparent, that did not quite work out. So, instead, he ended up making films for the BBC. Lots of them. And yet the title of BBC journalist and filmmaker does not quite capture the man. Nor does it encapsulate his rise to prominence. In the 1980s, Curtis’ work was considered fringe. Indigestible to many, it was tolerated by some and intensely loved by few. He was an obvious outlier. But gradually, since the late 1990s, his unique outlook has gained respect. With that success, he became a filmmaker at large with no direct boss to report to and a steady budget to work with.

This rare freedom brought out the best in him, and by the early 2000s, Curtis was something of a cult figure, whose work is pirated as soon the BBC broadcasts it. After making it big across the pond, he was slowly discovered by the Americans, who began inviting him to film festivals, giving him awards and writing generously about his brilliance. They, too, struggled to account for the exact nature of his films. They draw you in, but what are they about, really? One answer is that no one really knows: Curtis’ films are about everything, and about nothing in particular. Indeed, his work defies easy characterization, and it borders on being so unreviewable that critics normally resort to an automatic 5-star verdict. I wish to alert the reader that this review is no exception.

Curtis’ oeuvre revolves around the human modern condition and while it includes footage of China, Africa, North America, the UK, Russia, and the Middle East, he does not need to travel far. A short commute to the enormous 80-year-old BBC archive suffices. It is, most likely, the biggest television archive anywhere in the world, and Curtis can do whatever he wants in it. This past January he described his working method to the New Yorker (yes, they have finally discovered him, too), which consists of watching thousands of hours of raw, unedited material in fast-forward mode until an image sparks his interest. Then, he takes it slow, and digs in. This careful curatorial act – which is performed by him rather than by a fleet of aspirational assistants – results in visual material which, though very familiar, feels entirely new and foreign to the eye. Then comes an unconventional soundtrack that produces a similar effect, so that even his take on the all-too-familiar Trump presidency feels entirely new, as if dealing not with the most-documented presidency in history but with a distant tribe in the Amazon encountering the camera for the first time.

Next comes the signature script, which is a frontal assault on linear narration and the British cult of “common sense.” Here, Curtis juxtaposes Grand history with the biggest G possible with individual experience set on the tiniest scale imaginable, down to the level of the atom. It is a filmmaking craft built around juxtapositions of scale, from neurological webs in the brain to global networks and back to the inner world of the self. All along, this journey is void of straightforward arguments and simple conclusions. Instead, it uses an associative and elusive mode of reasoning which is stitched together by “patterns.” Patterns that are so obvious and apparent to Curtis that it makes no sense at all to actually argue about them. Everyone can just see it, or maybe not. Probably not.

But that did not matter, as he would say, because by this time, Curtis had become a phenomenon. We can trace the rise of Curtism to the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of big ideologies and state-synchronized collective action. Divesting from utopias, the 1990s globalized neo-liberal world of Pax Americana quickly replaced revolution with money and instant pleasure. Instead of “Workers of the World Unite!” we got the ubiquitous mode of “Unlimited Everything for Everybody Now!” in which self-absorbing radical individualism was hailed as the new king (the selfie of the selfie, if you wish). Curtis thrives in this matrix and is probably his most consistent explorer. We know it by its collective name the “End of History;” a term which perfectly captures the essence of Curtism.

With more than thirty films to his name, including the post-Cold-War classics Pandora’s Box (1992), The Century of the Self (2002), The Power of Nightmares (2004), HyperNormalisation (2016) and now, the monumental seven hour magnum opus Can’t Get You Out of My Head (2021), Curtis has assembled an impressive record that both critics and admirers describe as fragmented, disjointed, avant-garde, experiential, nonsensical, incoherent but still, utterly brilliant, mesmerizing and genuinely captivating.

So, what is going on here? Is Curtis a journalist, a historian, an experimental artist, all and/or none of the above? For his part, Curtis insists he is a journalist whose exclusive subject is “power and politics.” It sounds simple and straightforward but it really isn’t. In journalism, the reader or viewer does not have to second-guess the scale and dimensions of the subject at hand. Here, when after many hours of watching my wife asked me whether I was finally done, I truly did not know what to answer. Am I? Is it over? And mind you, unlike the New Yorker, I am not a newcomer to the Curtis scene.

How did I hear of Curtis? Fifteen years ago, a Portuguese colleague recommended The Century of the Self, a classic Curtis film about how Freud’s theory of the unconscious was picked up by the American PR and advertising industry for the sake of mass marketing and Cold War population control. “Recommended” is not really the appropriate verb to the describe the actions of my colleague. To recommend Curtis is never the generic Netflix-nudge of “you must see the new whatever” – the “whatever” being something that will likely drain your soul and leave no cognitive trace in your brain aside from a certain numbness. To “recommend” Curtis is to gently follow-up with the recommendee, in the following days, weeks and months, prod when you need to, and be sure that the message sinks in. If she fails to engage – as recently happened with someone to whom I “recommended” Curtis – you have to leave your manners behind, double down on your efforts and be ready to press the matter further.

Upon success, you then invite yourself to her virtual living room to start a conversation. By that point, if you choose your victims intelligently, the conversation will have a life of its own. In other words, to recommend Curtis is not to extend the casual invitation to share something that is reasonably good and popular. Rather, it is an initiation process into a cult. The kind of cult which never really works as, aside from all the admiration for Curtis’ genius visual extravaganza and idiosyncratic reasoning, it is never quite clear what you are actually worshiping. What are the films about? What do they mean? And why should we care? And this is exactly the point.

All Curtis films begin with the innocent and promising fairytale line “This is a story about …” only to find out 2-3 minutes later that there is no story, or that it has shifted and is about to change yet again, or that it was, all along, the wrong story and that you were actually duped. There is no beginning, middle, or end, just his signature speech pattern of smooth transitions from one “obvious” pattern to the next. Here are some classic lines: “At the heart of it . . .”, “but at the very same time . . .”, “they claimed . . .”, “but in the process . . .”, “But that did not matter . . .”, “But this was a fantasy . . . in fact . . .” and so on and so on. Did I understand anything the first time I watched his work? No, yes, it does not really matter because I was immediately mesmerized by the captivating aesthetics and the occasional brilliant insight. Let me show you how it works. Watch this trailer to HyperNormalisation. Now watch the Adam Curtis parody by “common sense” BBC viewers who have had enough (over there they pay for their public broadcasting). Now answer: Style over substance? Hyperbolic claims? Or, rather, a high-minded exploration of how we got from here to there, why, and who benefited? Who to believe? Do you want to watch more?

Let’s discuss the latest masterpiece Can’t Get You Out of My Head which I automatically award as many stars as Curtis would like. With this new production, Curtis has brought his craft to perfection. Like a good DJ, he drew on previous projects, mixing them with new material to create something familiar yet exciting, unexpected and mightily relevant. Released straight after the US elections, the first scene, hits the viewer with the image of President Obama and the subtitle “if you liked this, you will also like that,” following which President Biden makes an entry. But though accessible from the very first minute, that does not mean you can just go ahead and watch the whole 10 hours straight on. If you just turned 21 and are going to your Curtis neighborhood pub for the first time, don’t empty the best and most expensive bottle of scotch in one long sip just because you can. Take it easy and start with something lighter like The Power of Nightmares, about how American neo-conservatives and Islamic jihadis jointly made the 9/11 world in which we are still living. Or even Pandora’s Box, subtitled A Fable from the Age of Science about Cold War technocratic rationality, system analysis, game theory and the impending rule of algorithms. Anticipating the current era of Big Tech mind-shaping and soul-bending – and well ahead of the game – Curtis made this one in 1993. It might strike you as slightly outdated but this is alright, as you will find here many of the vintage themes of a good Curtis movie and begin to train your eye and brain. Besides, your liver is probably not yet ready for the strong stuff. Come back tomorrow, and in the meantime watch this quick BBC introduction, from Curtis’ Oh Dearism (2009) about the meaninglessness of mainstream television news media.

Welcome back. Meet some of the characters in Can’t Get You Out of My Head. Every Curtis film has a unique set of characters. Some are large-scale familiar actors like the Libyan ruler Muamar Qadafi, Chairman’s Mao’s wife Jiang Qing and Vladimir Putin. Alongside them, but on equal footing, you will find the rapper Tupac Shakur (2Pac) and his Black Panther activist mother Afeni Shakur. Then, you will be introduced to forgotten men and women like 1960s model turned novelist, Sandra Paul and the black slumlord executioner-turned-freedom-fighter-conman and murderer Michael X. Next in line are ordinary people like transgender activist Julia Grant, a British citizen who, during the 1970s, fought the psychiatrist establishment on camera to allow her a sex change operation. Also on board is the celebrated behavioral economist and Nobel Prize laurate Daniel Kahneman, American cultural subtour Kerry Thornley who, during the 1960s, presided over “Operation MindF***”, which spread conspiracy theories just to see what would happen (answer: a lot).

You can also meet people you’ve never heard of, like Kremlin master political manipulator Vladislav Yuryevich Surkov. Or, for instance, someone you have heard of, like al-Qaida jihadi and resident of Guantanamo Bay prison Abu Zubeida who, following a brain injury while fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, was “trapped in a perpetual now haunted by fragments of memory.” When interrogated by the CIA he turned the mental mishmash that included, among other things, Rambo III, into prime “intelligence” that satisfied his captors but was otherwise a piece of fiction. You will also meet innocent Irish convicts “The Birmingham Six”, British imperial archeologist and spy Gertrude Bell, distinguished members of the Ku Klux Klan and – last but not least – pharmaceutical industrialist Arthur M. Sackler and his family of drugs. There are also some impersonal characters such as “governments” “the CIA” “the Banks” “the Elites” “valium” and OxyContin.

Together, and in no particular order, these characters successfully carry sizable themes. As his most complete work to date and by his longest, Can’t Get You Out of My Head showcases themes such as mass dissociation of the middle class from the real world, de-industrialization, the slow (and then very fast) rise of China, 1960s counterculture, the rise of global systems, the dot com crisis, the 2008 crisis, populism, AI and algorithmic governance, the Iraq war as a video game detached from the realities at home, the crack epidemic and urban gangs, the gender revolution, the Saudi fairytale reality, apocalyptic terrorism, humanitarian aid, Chaos Theory, how the CIA overthrew 66 foreign governments, metadata, and James Bond.

Zipping from one theme to another to follow the pattern and flow of power, Curtis presents moments of sheer cinematographic brilliance. In one such scene, a camera slowly enters the compound of jihadi men in Peshawar, Pakistan, and moves slowly between them zooming in and out on their faces to the soundtrack of “The Lady in Red” by Chris De Burge (apparently, Abu Zubeida’s beloved track). You don’t need more than that in order to understand the madness of it all. Another memorable moment comes as the camera follows an Iraqi journalist in one of the biggest sandstorms recorded in Iraqi history, just days before the American “Operation Desert Storm.” These 50 seconds anticipate the disaster better than any learned explanation.

In another sequence, we move from Pakistan to 2Pac’s visions of revolution and then straight to the Eiffel Tower and the French Revolution and then to the collapse of the Soviet utopia. There are scenes in which Curtis does try to provide a learned explanation, for example of the subprime mortgage crisis, but ends up delivering a superficial statement about the complexity and intelligibility of the computer networks that caused the problem. In such moments, Curtis moves from the sublime to the farfetched in the space of a few minutes. If you get tired and want to get to the end of it quickly, watch episode six, which is the most coherent of them all, but also the one that can largely stand on its own. The series ends with a quote from the late radical anthropologist David Graeber that more or less captures Curtis’ life-long motto: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world, is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

Do not mistake this final line by an emerging guru of the alternative Left as an indication that Curtis is taking sides in politics. This is a strictly metapolitical affair. Curtis himself believes that all he does is chronicle phenomena that exist outside the ubiquitous categories of public perception. That we fail to make sense of the liquid we all swim in and the air all breathe. His work, he argues, looks behind the fake world we live in, where nothing is as real as it seems, to reveal how powerful actors impose modes of being and systems of thought and action on the rest of us. Sometimes these actors come from the right (Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan) and sometimes from the neo-liberal Left (pick your villain).

If, by the end of this long review cum introduction to Curtis, I must say something concrete about him, it is that he is the master and prince of a radical postmodern documentary style. It is a style that has no ordered Enlightenment narrative but just a pure and powerful effect that passes as truth and rings as such with no trace of American-style conspiracy theories for which he has no patience at all.

It is all fascinating and very historical. But it is not history. And yet, now, when Curtis has finally made it in America, it might pass and come to be viewed as historical truth. In fact, I am curious to see which university will start the first Adam Curtis Program in Critical Visual Arts. I predict it will be NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, but UT Austin, with its associative SXSW ambience, may surprise me too. I look forward to the first class to graduate from this program and convene the inaugural “We Are all Adam Curtis” conference, to which I expect an invitation as a keynote speaker.

And as for you, dear reader, welcome to the cult, and don’t expect it to make much sense.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

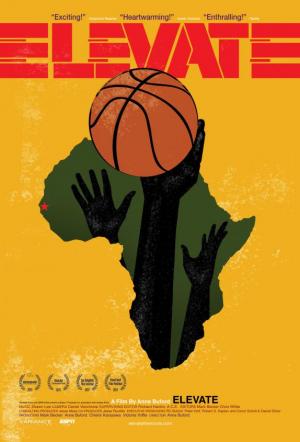

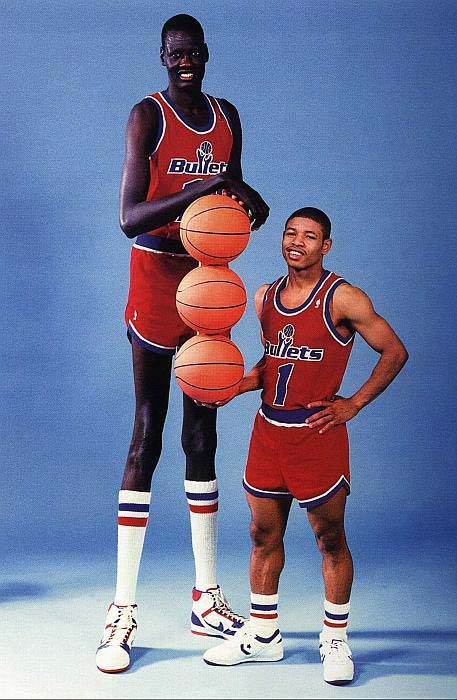

we witness the trials and tribulations of urban youths trying to move beyond the difficulties that they face in their daily lives in Senegal. The documentary begins at the SEEDS Academy, the project of Amadou Gallo Fall, a personnel director for the Dallas Mavericks. Essentially, the SEEDS Academy is described as an attempt to create a boarding school for Senegalese youths to hone their basketball and academic skills and eventually (hopefully) receive a scholarship to play basketball at a prestigious prep school in the US. Beyond this, each of the young Senegalese students profiled in the ESPN funded documentary hope to play college basketball and eventually make their way to the NBA.

we witness the trials and tribulations of urban youths trying to move beyond the difficulties that they face in their daily lives in Senegal. The documentary begins at the SEEDS Academy, the project of Amadou Gallo Fall, a personnel director for the Dallas Mavericks. Essentially, the SEEDS Academy is described as an attempt to create a boarding school for Senegalese youths to hone their basketball and academic skills and eventually (hopefully) receive a scholarship to play basketball at a prestigious prep school in the US. Beyond this, each of the young Senegalese students profiled in the ESPN funded documentary hope to play college basketball and eventually make their way to the NBA. the fact that these students primarily speak French. Some of the most intriguing moments in the documentary involve issues of religion and alienation in the new environments that surround these young students. Both Assane and Aziz are Muslim and it is evident that in both of their respective schools, practicing Islam is not well understood by their peers. This is particularly poignant in a dining hall conversation that Aziz has with one of his schoolmates who knew little about Ramadan, but was curious why Aziz was abstaining from eating during their mealtime. We later see Aziz breaking fast alone in his dorm room. Buford also captures a sense of Assane’s religious isolation in her juxtaposition of school-wide church services in the religiously-affiliated prep academy and his solitary prayer sessions in his dorm room. Despite these difficulties, at one point, Dethie lands a position at the same school as Assane. As a result, Assane is able to guide him through such a large cultural, physical, and mental transition. In the end, we are left with a bittersweet message of hope. All of the students in the documentary continued their education in the United States and played basketball at the college level at schools ranging from Carroll College in Montana to the University of Virginia where Assane was a starting center.

the fact that these students primarily speak French. Some of the most intriguing moments in the documentary involve issues of religion and alienation in the new environments that surround these young students. Both Assane and Aziz are Muslim and it is evident that in both of their respective schools, practicing Islam is not well understood by their peers. This is particularly poignant in a dining hall conversation that Aziz has with one of his schoolmates who knew little about Ramadan, but was curious why Aziz was abstaining from eating during their mealtime. We later see Aziz breaking fast alone in his dorm room. Buford also captures a sense of Assane’s religious isolation in her juxtaposition of school-wide church services in the religiously-affiliated prep academy and his solitary prayer sessions in his dorm room. Despite these difficulties, at one point, Dethie lands a position at the same school as Assane. As a result, Assane is able to guide him through such a large cultural, physical, and mental transition. In the end, we are left with a bittersweet message of hope. All of the students in the documentary continued their education in the United States and played basketball at the college level at schools ranging from Carroll College in Montana to the University of Virginia where Assane was a starting center.