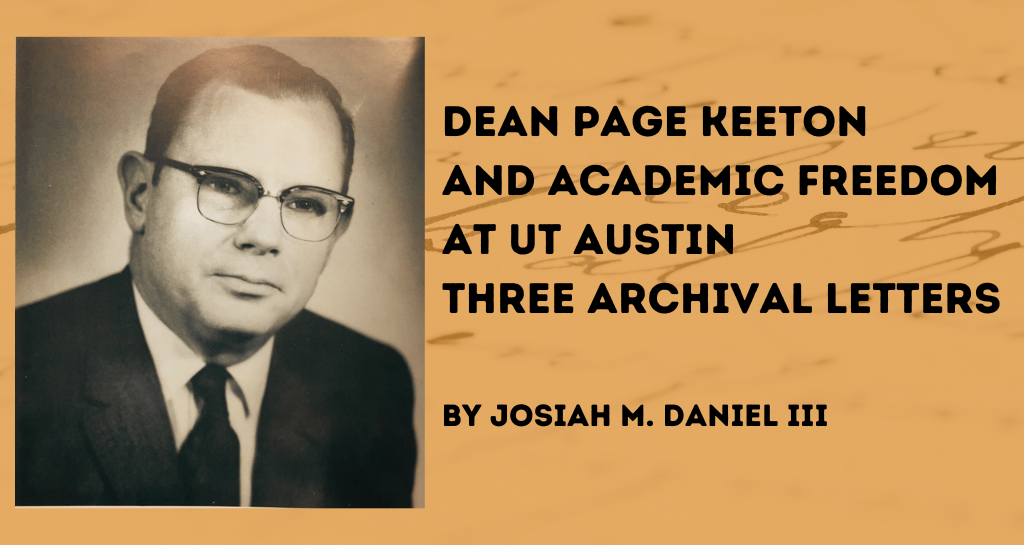

One bonus of archival research is discovering documents irrelevant to the topic but so evocative that they can’t be ignored. In the State Bar of Texas archives, I found three letters from June 1960 between Werdner Page Keeton (1909-1999), Dean of the School of Law of The University of Texas, and two lawyers. Those letters caused me to detour from my project for a while.

Source: Law School Yearbook, 1959.

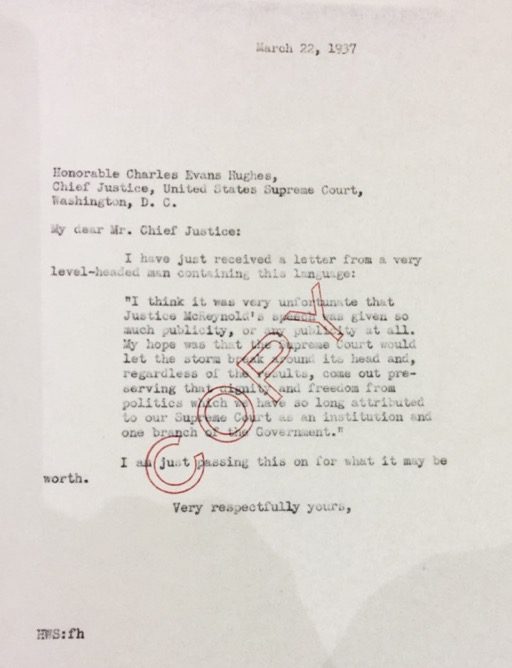

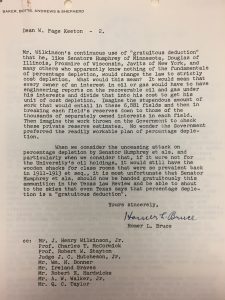

Homer L. Bruce, a tax-law partner of the Houston law firm Baker & Botts, sent the first letter to Keeton on June 15, 1960, with “carbon copies” to nine prominent members of the legal profession in Texas. Six days later, one of those nine recipients, a renowned oil and gas lawyer in a Fort Worth firm, Robert E. Hardwicke, also wrote Keeton. Both letters complained strongly about an article just published in the law school’s Texas Law Review by a UT tax-law professor, J. Henry Wilkinson, Jr. The article was titled “ABC—From A to Z,” and the letter writers were outraged that Wilkinson criticized a tax benefit for oil and gas companies known as the “percentage depletion allowance.” The third letter is Keeton’s June 28 response.

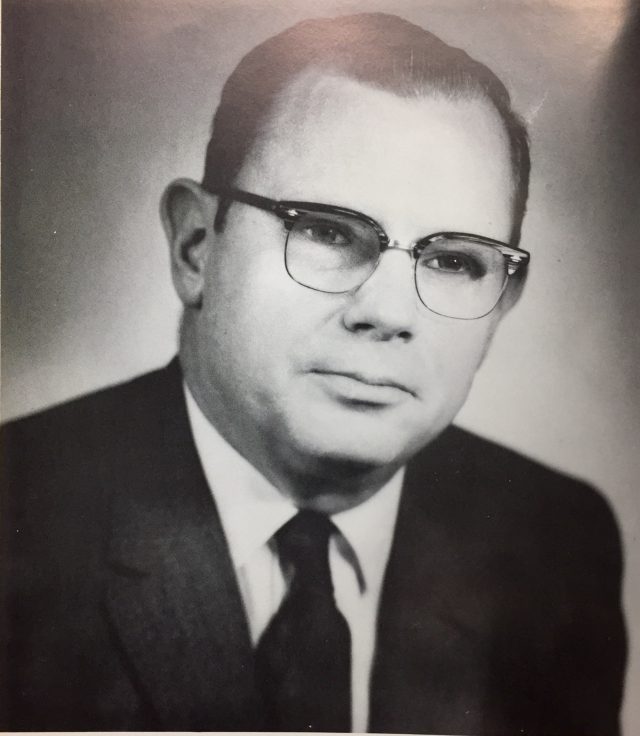

Source: State Bar of Texas, Archives Dept., via author.

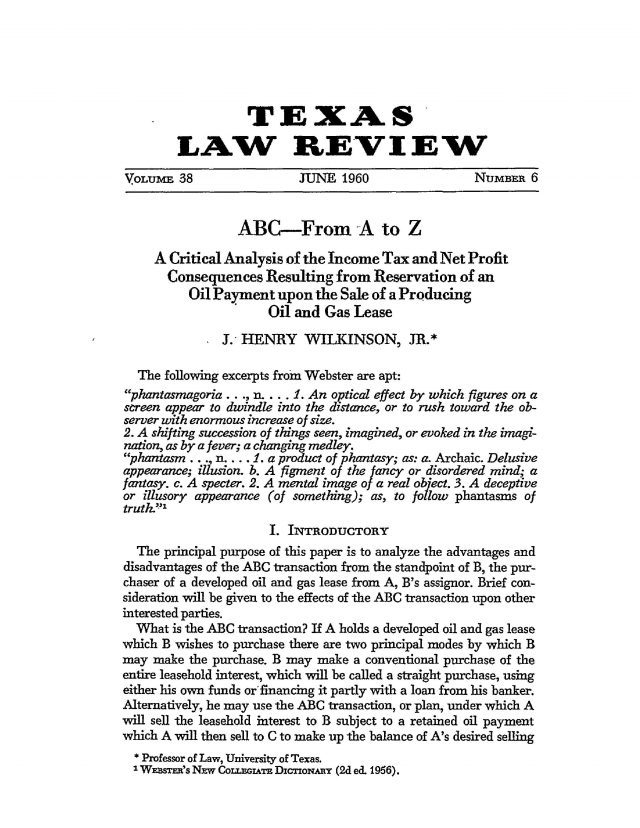

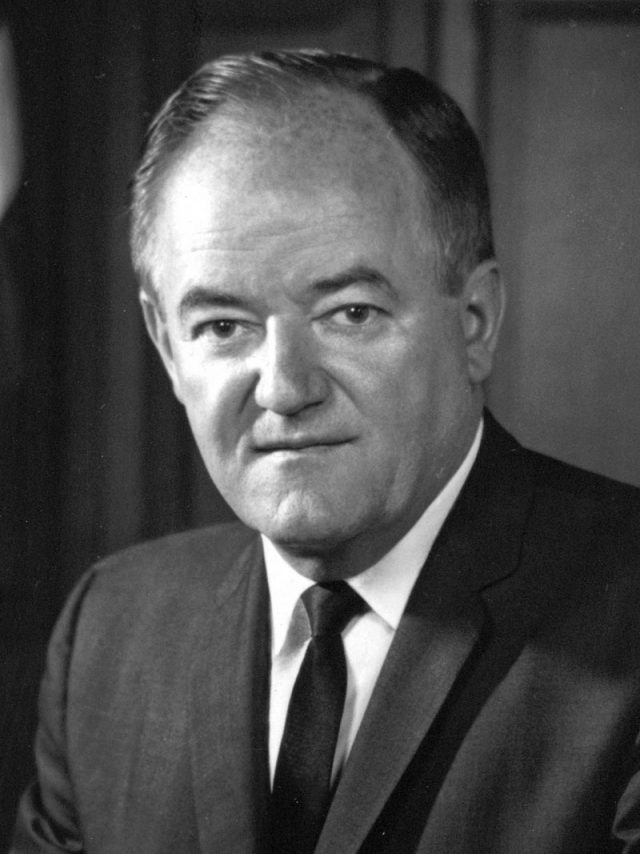

The challenged article seems unremarkable today. Wilkinson’s topic was the “ABC” transaction, common in the oil-and-gas business. A producing property’s owner may sell a “production payment,” or a fixed quantity of the minerals to be produced, to a purchaser in a manner that takes advantage of the federal income-tax “allowance,” or deduction, of 27-1/2% of the property’s income, available to oil-producing taxpayers for the “depletion” resulting from the extraction of the minerals in the ground. Through patient examples, Wilkinson demonstrated that the ABC deal was not always as tax-advantageous as was believed. The article did refer to the allowance as “gratuitous.” And that observation drew the ire of Bruce and Hardwicke, who amplified their criticism by insisting that enemies of the depletion allowance—specifically, Hubert H. Humphrey—would use Wilkinson’s characterization of the percentage depletion allowance as “ammunition.”

Source: www.heinonline.com

In June 1960, when these letters were written, the Democratic Party’s national convention was a month away, and one still-active candidate for the presidential nomination was indeed Hubert Humphrey, then a two-term Senator from Minnesota who had consistently fought the depletion allowance in Congress. His fight against that and other “tax loopholes” had been unsuccessful but earned him respect as a reformer. In Texas, however, the depletion allowance was a sacred cow. The Texas Law Review had published an earlier article defending the depletion allowance, and the Chair of the Texas Railroad Commission, Ernest O. Thompson, wrote and spoke in favor of the allowance, and virtually all of the national legal literature and newspaper coverage in Texas about the allowance defended it. And Humphrey’s rival from Texas, Lyndon B. Johnson, was a protector of it. Humphrey later became LBJ’s vice-president but “never gave up” and, finally, in 1975, was gratified to see Congress abolish this tax “loophole.”

Source: WikimediaCommons

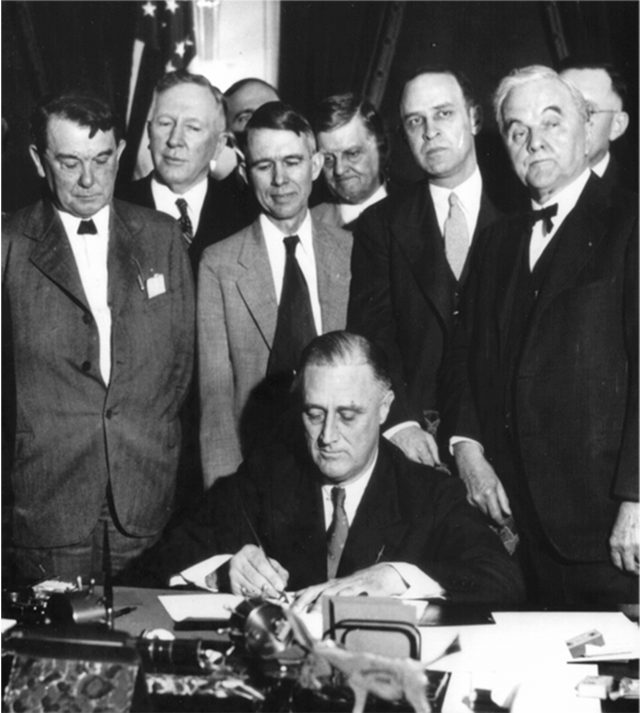

The addressee of the two letters, Keeton, was well acquainted with the oil and gas industry and its issues. He had earned the LL.B. in 1931 at UT, was hired to teach there, and quickly gained recognition in the field of torts, the law of civil injuries, and wrongful death. During World War II, he served in Washington as an executive of the Petroleum Administration for War. After a stint as dean of the Oklahoma University Law School, he accepted the deanship of UT’s law school in 1949, serving until 1974. He distinguished himself at both law schools by fostering racial integration and by continuing to teach torts as well as serving as dean. The law school grew during his deanship, and UT law alumni/ae revere Keeton. The city of Austin renamed the street alongside the law school for him, and he is buried in the State Cemetery by gubernatorial proclamation.

Moreover, Keeton was stalwart and adept, in protecting academic freedom at the law school. One innovative key to his success there was to liberate the school from overreliance on legislative appropriations by creating the UT Law School Foundation to receive alumni/ae contributions. Important supporters of this initiative were law graduates who attained positions of power within the oil and gas industry. For instance, Rex G. Baker of Humble Oil was a key supporter of the Foundation—and also a staunch defender of the depletion allowance.

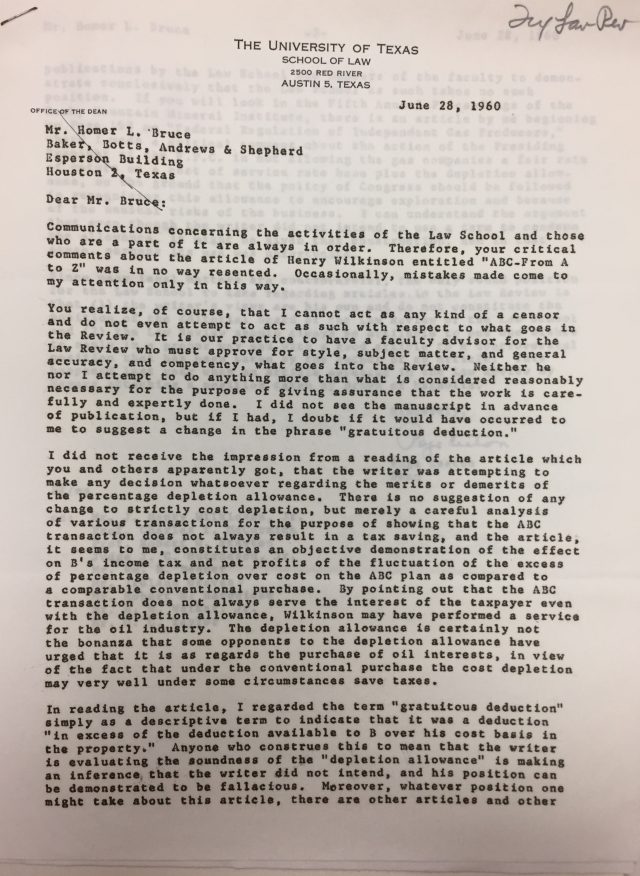

Those relationships did not deter him. Keeton formulated a masterful response to the two letters that foreclosed any further discussion. “You realize, of course,” he began, “that I cannot act as any kind of a censor and do not even attempt to act as such with respect to what goes in the Review.” Having matter-of-factly vindicated academic freedom, the Dean added that he did not read Wilkinson to make any judgment about “merits or demerits of the percentage depletion allowance.” And by pointing out that the ABC structure does not always work as expected, “Wilkinson may have done a service to the oil industry.” Keeton also observed that the challenged word “gratuitous” was simply “a descriptive term,” indicating that the amount of the tax deduction was not tied to the cost of the property; the tax benefit was indeed essentially free to the oil and gas taxpayer.

Source: State Bar of Texas, Archives Dept., via author.

Academic freedom at UT has had a long history. In 1917, when Governor James E. Ferguson vetoed appropriations for UT because the President would not dismiss faculty to whom Ferguson objected, the Legislature, at the urging of UT alumni/ae, impeached and removed him. In his 1986 oral history interview, Keeton recounted less spectacular but nonetheless significant instances during his tenure of politicians and the Board of Regents seeking to meddle with the faculty and academic matters, efforts Keeton successfully repulsed. But Keeton’s defense of academic freedom was not always public, as in the example of these previously unknown letters in the archive. Keeton’s handling of that situation in June 1960 highlights the ongoing task of University leaders to protect academic freedom, and it burnishes both Keeton’s legacy and the reputation of UT as a place for the free exchange of knowledge and viewpoints.

The State Bar of Texas’s Archives Department, also known as the “Gov. Bill and Vara Daniel Center for Legal History,” contains the Bar’s permanent records. The Archives’ professional archivist also manages and provides access to the collections of the Texas Bar Historical Foundation there. The archives are located in the Texas Law Center in Austin, Texas. The three letters were contributed to this archive in 1992 by J. Chrys Dougherty, a historically minded lawyer; his father-in-law, Ireland Graves, was one of the nine cc recipients of the three letters.

Josiah Daniel (UT Law, J.D. 1978; UT History, M.A. 1986) is a Retired Partner in Residence of the international law firm Vinson & Elkins LLP in its Dallas, Texas office. After four decades of law practice, he now is focusing on the history of the legal profession in Texas and is writing a biography of Dallas congressman Hatton W. Sumners (1875-1962), based on his papers in the Dallas Historical Society’s archive. His C.V. is on his blog: http://blog-josiahmdaniel3.blogspot.com/2018/03/cv.html. He may be reached at jdaniel@velaw.com.

Sources for this article include:

Lewis L.Gould, Progressives and Prohibitionists: Texas Democrats in the Wilson Era (Austin: UT Press, 1973).

“W. Page Keeton, An Oral History Interview” (Austin: UT Austin School of Law, Tarlton Law Library, Legal Bibliography Series No. 36 (1992) 49-52, 69-74.

Theodore H. White, The Making of the President 1960 (N.Y., Harper, 1963)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.