By Ben Weiss

In Age of Anger: A History of the Present, acclaimed author and journalist Pankaj Mishra explores what he describes as the tremors of global change. For the past several decades, liberal cosmopolitanism provided a false sense of security after the fall of the Soviet Union. Now, Mishra claims, world schisms have begun to manifest in increasingly overt displays of violence by state and non-state actors alike, leaving dubious possibilities for the coming years. In this accessible work of public history, Mishra traces a long arc of the rise of the Age of Anger from the Enlightenment to what he perceives as the precarious present.

In Age of Anger: A History of the Present, acclaimed author and journalist Pankaj Mishra explores what he describes as the tremors of global change. For the past several decades, liberal cosmopolitanism provided a false sense of security after the fall of the Soviet Union. Now, Mishra claims, world schisms have begun to manifest in increasingly overt displays of violence by state and non-state actors alike, leaving dubious possibilities for the coming years. In this accessible work of public history, Mishra traces a long arc of the rise of the Age of Anger from the Enlightenment to what he perceives as the precarious present.

The book was written and published as we watched the explosion of chaos in Syria and Iraq, the collapse of established and relatively balanced political and economic relationships, increases in terrorist activity in places such as Turkey, Kenya, and Nigeria, and increasing violence stemming from racial prejudices in France, Great Britain, and the United States. The rise of rancorous populism cracking its way through the foundations of traditional model democracies in the West, evidenced by the success of Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, and Brexit, leads Mishra to fear that the globe is on the precipice of world wide disaster.

“After a long, uneasy equipoise since 1945, the old west-dominated world order is giving way to an apparent global disorder.” This new disorderly Age of Anger ranges both from the destabilizing fury of history’s marginalized populations as well as the counterrevolutionary response that has mobilized hatred within mainstream political discourses. Unfortunately, Mishra offers little perspective on how the world may emerge from this predicament. For him, the tumultuous year that was 2016 is only the beginning.

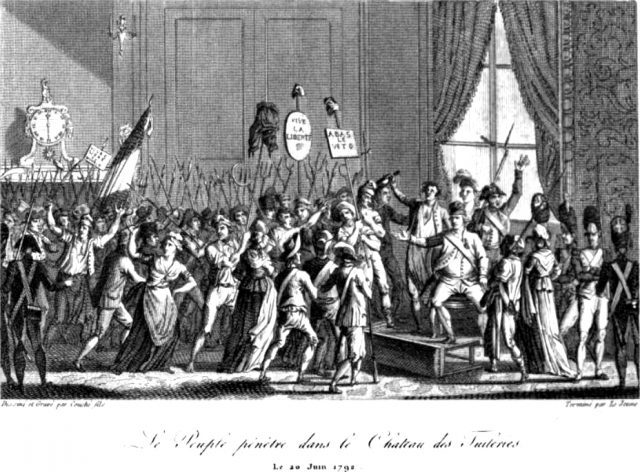

The real value of this fairly pessimistic yet stimulating work is in Mishra’s analysis of how we arrived in the Age of Anger. Scholars in subaltern and imperial histories have argued for decades that the sheer arrogance of narratives of Western liberal progress have concealed the crumbling foundations of modernized globalization. Mishra offers an accessible and nuanced narrative of the emergence of popular rage from the European Enlightenment, through the advent of industrialization and imperialism, and the various alignments of the non-Western world within a Eurocentric global order during the twentieth century. From the upheavals of the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France to the rise of fascism in the twentieth century, he shows that the neatly packaged concept of liberal modernization mostly consists of a process of “carnage and bedlam.” Mishra argues that elites, unable to cope with the reality of modernization, take refuge in precipitating alienation: destruction of civil liberties, states of emergency, anti-Islamic movements, rhetoric purporting the global clash of civilizations, and the like. Though perhaps framed within too much of a polarized dichotomy, Mishra’s analysis reveals a massive schism between political and economic elites and the larger masses who have been directed into “cultural supremacism, populism and rancorous brutality” as a result of being denied the promised advantages of modernity. The consequential tension leaves us on the threshold of a “global civil war.”

Mishra predicts that continuing economic stagnation will exacerbate the bitterness of these existing divisions. Many will react to literal displacement from their societies or social and political displacement as we have seen with the recent and rapid expansion of activities in United States immigration. The subsequent fear and rage will divide those who may resort to radical violence because they have nothing left to lose from those who will empower more radical elites who promise to tear down the existing system. However, for Mishra, this chaos is fully representative of the process of liberal modernization. Once you strip the implications of liberal modernization of its positive rhetoric, what remains is a cacophony of violence. Slavery, imperialism, and warfare have always been the dark underbelly of the liberal project.

While modernization has generated the context for this violence to take on truly global proportions for the first time, Mishra’s detailed history describes the development of these themes through earlier centuries. For example, Voltaire routinely emphasized the exemplary capacity of humanity to exercise free will, however, he actively encouraged Catherine the Great to coerce Poles and Turks into Enlightenment education under threat of violence. All the while, Catherine’s actions allowed him to make a fortune in the commercial investments of new markets that arose as a result of this coerced ideological diffusion. Mishra also alerts readers to the various thinkers such as Rousseau and Nietzsche who prefigured the growth of dissident populations and their inevitable role as destabilizers during the emergence of modernization, drawing interesting parallels to the role of Islam in the twentieth century.

By demonstrating the connection of ideas in Europe with the rest of the world, Mishra is able to draw heavily from Nietzsche’s concept of ressentiment, which encapsulates the innate hatred and envy fostered by groups who are positioned as inferior. For example, ressentiment could describe the attitude of the colonized under imperial regimes. Mishra claims that Muhammad Iqbal, an Islamic poet and religious reformist, and Lu Xun, an activist in China all pulled from Nietzsche’s ideas, while “Hitler revered Atatürk” and “Lenin and Gramsci were keen on Taylorism.” This mix of Enlightenment thought with global adaptations speaks to the paradoxical fusion of self-contempt instilled by liberal otherization with the rage that facilitates resistance to the same system. Indeed, as Mishra contends, leaders from all over the global south and east met imperialism by synchronizing with Western ideology in order to secure their independence from the West. This aspiration failed locking much of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and various Marxist movements into liberal modernity. “The key to man’s behaviour lies not in any clash of opposed civilizations, but, on the contrary, in irresistible mimetic desire: the logic of fascination, emulation and righteous self-assertion that binds the rivals inseparably. It lies in ressentiment, the tormented mirror games in which the West as well as its ostensible enemies and indeed all inhabitants of the modern world are trapped.”

The Paris Commune stormed the Tuileries Palace in 1792 during the French Revolution (via Wikimedia Commons).

The ambitious project of Age of Anger is not without its faults, namely some oversights and generalizations. For one, Mishra does not consider social democracy or Marxism as the alternatives to neoliberal world systems that they perceive themselves to be. In other ways, his attempts to paint a larger history in broad strokes risks overgeneralizing some phenomena and exaggerating historical causality. Due to some of these flaws, proponents of liberalism may find his arguments unconvincing, but for those sympathetic to analysis of the darker sides of modernity, Mishra’s work should prove thought provoking while drawing attention to potential linkages in historical developments across multiple centuries in a way that brings arguments previously sequestered to academia into the public sphere.

Pankaj Mishra, Age of Anger: A History of the Present (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017).

![]()

Also by Ben Weiss on Not Even Past:

My Alternative PhD in History.

The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, by Robert C. Allen (2009).

Violence: Six Sideways Perspectives, by Slavoj Žižek (2008).

![]()