NEP’S Archive Chronicles explora el papel que desempeñan los archivos en la investigación histórica, ofreciendo una visión del proceso de realización del trabajo archivístico y de investigación. Cada entrega ofrecerá una perspectiva única de los tesoros y retos que los investigadores encuentran en los archivos de todo el mundo. NEP’s Archive Chronicles pretende ser tanto una guía práctica como un espacio de reflexión, en el que se expongan las experiencias de los colaboradores con la investigación archivística. En esta pieza, Raquel Torúa Padilla escribe de su experiencia encontrando las voces de los Yaqui a través de los archivos judiciales de Sonora.

Note: Click here to access English version

Nota: Haz click aquí para acceder a la versión en inglés

En mi búsqueda por entender la historia de los pueblos indígenas de Sonora, me he enfrentado a constantes desafíos para acceder a fuentes que reflejen auténticamente sus experiencias y perspectivas. Los registros históricos escritos por las poblaciones indígenas en el noroeste de México son escasos y difíciles de encontrar, particularmente aquellos anteriores al siglo XX. Para ese periodo, la mayoría de los individuos indígenas eran analfabetas, no hablaban el idioma de los colonizadores y carecían de recursos y medios para documentar sus pensamientos y sentimientos. Como resultado, nuestra comprensión de la historia indígena depende en gran medida de relatos escritos por personajes no indígenas, como misioneros, exploradores, figuras políticas o militares. Aunque en ocasiones podemos tropezar con valiosos documentos escritos por los propios nativos, como cartas de personas letradas, estos hallazgos tienden a ser excepcionalmente raros.

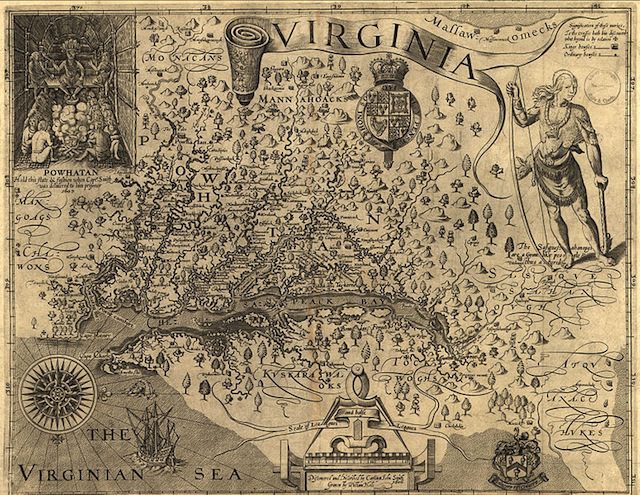

Me he interesado particularmente en la historia del pueblo Yoeme, mayormente conocido como Yaqui. Los yaquis conforman uno de los grupos indígenas más numerosos de lo que ahora se conoce como el estado de Sonora, en el noroeste de México. A lo largo de los siglos, han tenido que enfrentarse a diferentes autoridades y gobiernos que han buscado despojarlos de sus tierras, autonomía e identidad. A pesar de los esfuerzos por exterminarlos durante el Porfiriato (1876 – 1911), los yaquis persisten y resisten hasta el día de hoy.

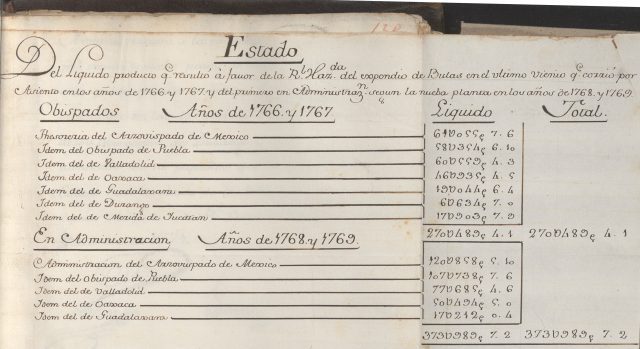

Como una solución al problema sobre las fuentes históricas, recientemente he recurrido a los archivos judiciales como una valiosa fuente alternativa para acceder a los testimonios indígenas. Hermosillo, la capital del estado de Sonora en el noroeste de México, alberga dos archivos públicos que contienen documentos jurídicos: el Archivo General del Poder Judicial del Estado de Sonora y el Archivo de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica de la Suprema Corte de Justicia. Ambos archivos dividen sus colecciones en dos categorías: el archivo histórico, que contiene documentos creados antes de 1950, y el archivo de concentración, que incluye documentos producidos después de 1950.[1] Ambos fueron creados en el siglo XIX y se mantienen y financian hoy en día a través de fondos asignados por el gobierno estatal y el gobierno federal, respectivamente.

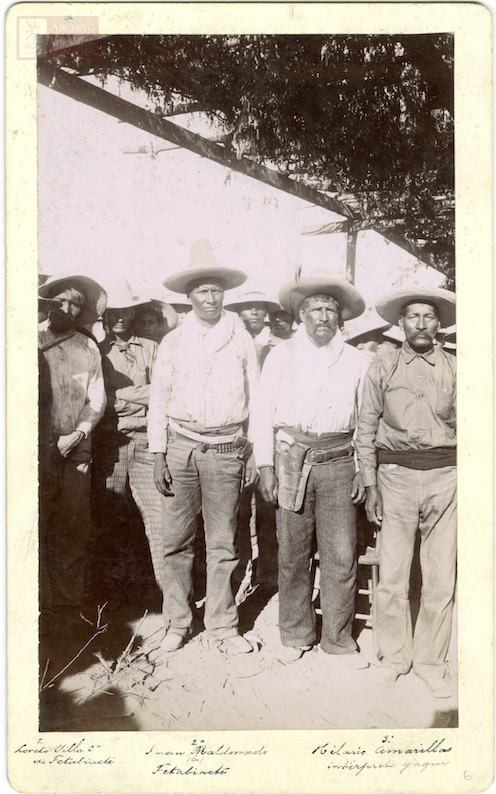

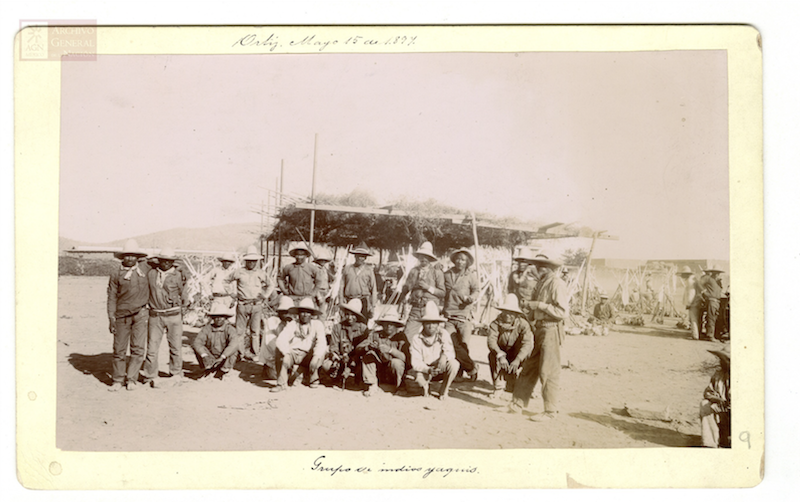

En los últimos años, me he dedicado a buscar en archivos históricos las voces del pueblo yaqui, especialmente del período conocido como la Guerra secular del Yaqui. Esta violenta etapa inició en 1824 bajo el liderazgo de Juan Banderas, un líder yaqui que se alzó contra el gobierno mexicano para defender su autonomía. El conflicto se agravó tras los proyectos liberales que buscaban privatizar las tierras comunales indígenas y, sobre todo, durante el Porfiriato, cuando se convirtió en una guerra de exterminio. Aunque apenas sobrevivieron a esos años, los yaquis continuaron su rebelión contra el gobierno hasta la década de 1930, cuando finalmente se rindieron tras ser ferozmente debilitados por las autoridades revolucionarias.

Aunque el contenido de ambos repositorios comparte similitudes, también hay diferencias notables emanadas de sus diferentes funciones y objetivos. Estas variaciones se manifiestan no solo en su contenido, sino también en la preservación, catalogación y facilidad de acceso a los documentos históricos. En este artículo, presento brevemente la historia de estos archivos y comparto mi experiencia de hacer investigación en ellos, y los resultados que podemos obtener.

Pero antes de entrar a los archivos, es necesario que explique cómo funciona el sistema judicial en México y cómo el expediente de un caso particular puede terminar en un archivo u otro. Desde la Constitución de 1824 y la creación de los Códigos Penales, los delitos en México se han clasificado como de fuero común o de fuero federal. Los casos de derecho común se procesan en los tribunales locales o estatales, mientras que los delitos de derecho federal van a los juzgados de distrito. Si una persona acusada (por cualquier tipo de delito) siente que ha sido sentenciada de manera injusta, tiene dos opciones a su disposición. Primero, pueden presentar una apelación para una revisión de la sentencia en una segunda instancia. Si esto no tiene éxito, pueden buscar ampararse ante la ley, lo cual se lleva a cabo en tribunales colegiados o, si es necesario, en la Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación.[2] Los delitos de fuero común son aquellos que afectan directamente a las personas, como el abigeato, el estupro, el robo, o infligir lesiones. Los expedientes de esos delitos (y de sus apelaciones, si se promovieron) se pueden encontrar en el Archivo General del Poder Judicial del Estado de Sonora (AGPJ). Los delitos de fuero federal, por otro lado, se definen como aquellos “que afectan el bienestar, la economía, el patrimonio y la seguridad de la nación”, como la sedición, el contrabando o delitos de inmigración.[3] La documentación relacionada con los delitos federales, así como cualquier proceso de amparo, se puede encontrar en el Archivo de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica de la Suprema Corte de Justicia (ACCJ).

Fotos tomadas por la autora

El archivo del Poder Judicial

El AGPJ, como todos los archivos, tiene su propia historia. Desde 1833, cuando el Estado de Occidente se dividió en Sonora y Sinaloa y se estableció la primera Constitución local en el estado, el decreto número 13 garantizó la permanencia de los Poderes Supremos, incluido el Supremo Tribunal de Justicia, en Hermosillo, junto con sus respectivos archivos. Más de un siglo después, en 1957, un nuevo decreto estableció un archivo especializado bajo la jurisdicción del Tribunal Supremo de Justicia para organizar y salvaguardar la documentación exclusiva del Poder Judicial del estado. La ley más reciente, de 1996, designó al AGPJ como un órgano auxiliar del Supremo Tribunal de Justicia, con el objetivo de profesionalizar y agilizar las operaciones del poder judicial.[4] Sin embargo los esfuerzos para identificar, catalogar y organizar la documentación no se han completado por cuestiones administrativas y de recursos.

Durante muchos años, la documentación de este archivo se mantuvo resguardada en el Archivo General del Estado de Sonora (AGHES), en la calle Garmendia, en el Centro Histórico de Hermosillo. Desde el año 2000, el archivo se trasladó a un nuevo edificio justo al lado de la Prisión de Hermosillo, en el Blvd. de los Ganaderos. El interior del archivo es todo lo que podrías esperar de un edificio burocrático, y aún peor, de uno judicial. La falta de ventanas, el espacio reducido y la decoración minimalista y utilitaria de la sala de consulta te invitan a ponerte en el lugar de las personas encarceladas cuyos expedientes encuentras frente a ti. Afortunadamente, puedes encontrar brillo y calidez en los archivistas, historiadores, y empleados del AGPJ.

Para tener éxito en la consulta de este archivo, es esencial establecer buenas relaciones con los archivistas, pues la consulta de la documentación presenta un desafío importante: no hay un catálogo ni una guía de referencia. Así que, o llegas al archivo ya con las referencias anotadas que viste citadas en el trabajo de alguien más (y a veces, incluso en ese caso, han sido modificadas), o es tu día de suerte y lo que buscas ya ha sido identificado por los archivistas. Dicho esto, debo reconocer los esfuerzos recientes del Poder Judicial del estado de Sonora por contratar historiadores y archivistas para trabajar en la preservación y catalogación de los 3036 legajos.

Yo llegué con una lista de referencias de los documentos que quería consultar, porque un amigo mío había estado ya consultando ahí y me guió hacía un expediente interesante. Después de llenar un formulario especificando la referencia, me solicitaron una identificación con foto y a continuación fueron a buscar los documentos. Me pidieron que usara guantes de látex, una mascarilla y que manejara los documentos con cuidado. Desafortunadamente, después de horas de pasar una página tras otra, no pude encontrar el caso que estaba buscando. Pero como siempre ocurre con el trabajo de archivo, encontré muchos otros documentos interesantes y relevantes para mi tema de investigación.

Archivo judicial federal de Sonora

Visitar la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica es una experiencia diferente. El edificio del archivo, antes una vivienda, fue construido en 1945 y está ubicado en la colonia Casa Blanca en Hermosillo, frente al icónico Parque Madero. En 1998, la Suprema Corte de Justicia adquirió la propiedad para utilizarla como la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en Hermosillo, que es mucho más que solo un archivo. Nombrada en honor al “Ministro José María Ortiz Tirado,” esta Casa es una de las 36 en todo el país que sirve como un espacio público para “promover la cultura jurídica, favorecer el acceso a la justicia y el fortalecimiento del Estado de Derecho.”[5]

Se requiere que los visitantes firmen una carta comprometiéndose al uso responsable de los materiales documentales y a compartir cualquier publicación con el Archivo. Para solicitar archivos específicos, los visitantes deben proporcionar detalles como el fondo (“Amparo” o “Penal”), el año, la referencia numérica, y los nombres de las personas procesadas. Curiosamente, a pesar de ser necesario presentar esta información para la consulta, el archivo no tiene un catálogo propio.

Para la colección Amparo, tuve que visitar primero la biblioteca de la División de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Sonora para revisar dos catálogos. Estos fueron producidos por Hans Ildefonso Leyva Meneses (que cubrió los años de 1900-1917) y Mayel Barboza Enciso Ulloa (de 1918-1928) como parte de los requisitos para obtener su título de licenciatura.[6] Afortunadamente, un catálogo digital completo de la colección Penal, aunque escrito de forma anónima, ha estado circulando entre los historiadores locales durante años (¡un agradecimiento al autor!).

La sala de consulta es completamente distinta a la del archvio estatal. Está bien equipada, es espaciosa y cómoda, y ofrece a los investigadores una vista a un jardín con árboles y cactus, así como a una hermosa familia de felina (entendible, pueso que las instituciones federales suelen tener más recursos). En este archivo también se requiere usar guantes de látex y una mascarilla. Desafortunadamente, debido a las medidas de protección de identidad pues los fallecidos también tienen derecho a la privacidad, no se permite fotografiar los documentos. Como resultado, una consulta exhaustiva puede llevar tiempo y esfuerzo, pero vale la pena.

Los documentos y las voces que podemos encontrar

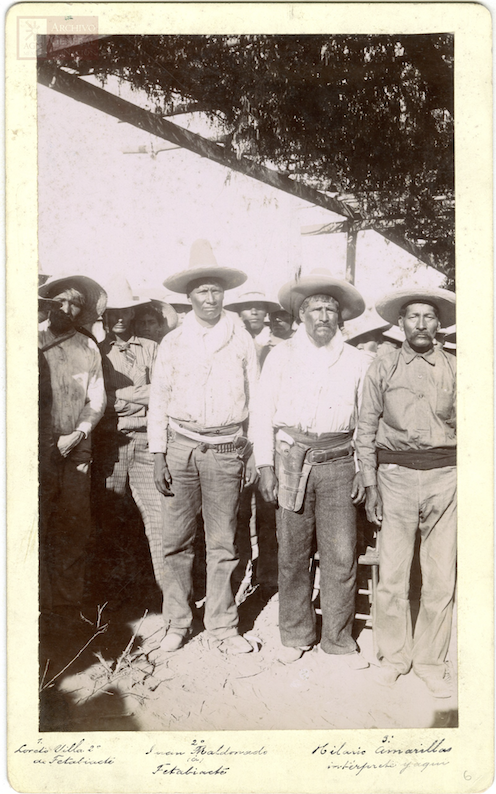

Respecto a los documentos, existen parecidos en cuanto a formato, secuencia, propósito y contenido. La extensión de cada expediente dependerá de la gravedad del delito, el número de personas involucradas, la complejidad de la investigación y el volumen de pruebas. El vocabulario y la estructura de los documentos de finales del siglo diecinueve son rígidos y formales, y muestran la ideología positivista de la época. La estructura del documento típicamente consiste en tres partes principales: descripción del crimen y de los involucrados, testimonios y pruebas, y la sentencia o veredicto. Aunque analizar todo el caso puede arrojar luz sobre las sutilezas del sistema judicial, generalmente suelo concentrarme en analizar las declaraciones y relatos, porque es aquí donde comienzas a encontrar las voces de los indígenas. Afortunadamente, debido a la burocracia del sistema judicial, los documentos incluyen la información biográfica de los involucrados, como nombre, edad, estado civil, ocupación y lugar de nacimiento y residencia, seguida de descripciones físicas de los acusados. Además de lo anterior, los documentos también suelen indicar si alguno de los involucrados era una persona indígena. Sin embargo, las autoridades no solían ser explícitos en cuanto al grupo étnico. Es decir, solo sabemos que la persona era indígena.

Para determinar si el individuo en cuestión pertenecia a la etnia yaqui, los indicadores más importante suelen ser el nombre y apellido—como Bacasegua, Buitimea o Matus, apellidos comunes dentro de la etnia. Además de esto, la ubicación de los eventos puede ser un indicador importante, particularmente si se mencionan locaciones dentro o cerca al territorio yaqui, como Guaymas, Vicam o Potam. Si bien este método es efectivo, es importante señalar algunos posibles problemas. En primer lugar, es fácil confundir erróneamente a los yaquis y a los mayos (otro grupo indígena de Sonora) debido a sus similitudes culturales y lingüísticas. Asimismo, a lo largo del tiempo, los yaquis han mostrado una movilidad significativa por todo el estado e incluso más allá de las fronteras políticas, por lo que no era raro encontrarlos desde Álamos hasta Cananea.

Aunque los expedientes judiciales son una importante fuente histórica para el estudio de los pueblos indígenas, es importante aclarar que sus prespectivas y cosmovisiones no están intactas en el archivo. Para esto, es crucial entender cómo se recogieron sus testimonios durante el proceso. Por lo general, en los procedimientos regulares, respondían a preguntas específicas hechas por las autoridades, en lugar de poder testificar de manera espontánea y libre. Por otro lado, si el individuo o individuos buscaban promover un amparo, se presentaba su testimonio por escrito ante la Suprema Corte. También es importante enfatizar que las declaraciones en los documentos de procedimiento civil o penal no son transcripciones literales. En cambio, fueron transcritas por los escribanos en un formato abreviado y pulido a través de una narración indirecta.

En este sentido, podríamos pensar que los expedientes de amparo serían un testimonio menos manipulado, ya que eran los mismos afectados quienes presentaban el testimonio. Sin embargo, considerando el contexto histórico y los casos de amparo que he consultado, los yaquis que promovían el amparo rara vez estaban alfabetizados. En muchas ocasiones, otras partes interesadas asistieron en el caso, a menudo con intereses personales en juego. Por lo tanto, además de los testimonios judiciales orales y escritos, se pueden encontrar esporádicamente otros tipos de evidencia, como cartas, recibos, contratos e incluso evidencia material. Pero si lo que tenemos a nuestra disposición es un testimonio de los indígenas filtrado y manipulado por terceros ¿cómo podemos encontrar sus voces y cosmovisiones? Tener una comprensión profunda del contexto histórico y de cómo se llevó a cabo el proceso judicial sugiere el mejor punto de partida.

Analizar cuidadosamente las declaraciones, contrastarlas y compararlas con otras fuentes (tanto primarias como secundarias) nos permite identificar posibles sesgos, malentendidos, distorsiones o supresiones. Interpretar las fuentes a partir de enfoque indígena también puede ayudarnos a obtener información sobre el significado, el vocabulario, las sutilezas, las implicaciones e incluso los silencios de los testimonios. Con un análisis exhaustivo, los documentos judiciales pueden ofrecernos un vistazo, y a veces incluso más, de las perspectivas, valores y cosmovisiones de los yaquis. Estos archivos son una ventana para observar cómo los yaquis navegaron e interactuaron con el sistema legal mexicano en un momento en que el gobierno los perseguía y buscaba exterminarlos, y cómo fueron representados o mal representados en los procesos judiciales.

Los documentos judiciales muestran cómo los yaquis fueron blanco no solo de las depredaciones del gobierno, sino también de la población sonorense, y cómo también fueron perpetradores de crímenes de fuero común y federal durante el periodo de guerra. Estos expedientes proporcionan detalles y testimonios sobre revueltas, “actividades sediciosas” y la desobediencia en general al gobierno, mientras nos ofrecen también un vistazo a sus vidas cotidianas y las distintas maneras de resistir a la guerra.

Las colecciones del Archivo del Poder Judicial del estado de Sonora y del Archivo de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica ofrecen valiosas perspectivas sobre la historia del pueblo yaqui en el siglo XIX y principios del siglo XX. Espero que mi experiencia, enfoque y metodología puedan ser un modelo para aquellos interesados en profundizar en documentos legales en otras partes de México, ya que cada entidad federal tiene sus propias sucursales de estos archivos. A pesar de los desafíos que cada uno de ellos presenta, estos arcervos son una fuente rica y a menudo infrautilizada de información para los historiadores que investigan no solo sobre asuntos legales, sino también sobre la historia más amplia de Sonora y sus poblaciones indígena y no indígena.

Quiero expresar un agradecimiento especial a todos los archivistas del Archivo del Poder Judicial del Estado de Sonora, en particular a Bennya Román Flores, cuya generosidad y dedicación han sido fundamentales para la realización de este trabajo. También agradezco a los colaboradores de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en Hermosillo, en especial a Adrián Pérez, por su paciencia y constante apoyo mientras consultaba múltiples cajas de documentos.

Raquel Torua Padilla es doctoranda en el Departamento de Historia de la Universidad de Texas en Austin. Es licenciada en Historia por la Universidad de Sonora y actualmente es becaria de CONTEX. Su investigación se centra en la historia de los pueblos indígenas en el noroeste de México y el suroeste de EE.UU., con especial énfasis en el pueblo yaqui. Sus proyectos actuales examinan las milicias yaquis y su diáspora durante los siglos XIX y XX.

Los puntos de vista y opiniones expresados en este artículo o vídeo son los de su(s) autor(es) o presentador(es) y no reflejan necesariamente la política o los puntos de vista de los editores de Not Even Past, el Departamento de Historia de la Universidad de Texas, la Universidad de Texas en Austin o la Junta de Regentes del Sistema de la Universidad de Texas. Not Even Past es una revista de historia pública en línea y no una revista académica revisada por pares. Aunque nos esforzamos por garantizar que la información de los artículos procede de fuentes fidedignas, Not Even Past no se hace responsable de errores u omisiones.

[1] Los procedimientos para consultar el archivo de concentración son distintos. En el presente, sólo me dedicaré a explicar lo referente al archivo histórico.

[2] García Ramírez, Sergio. 1998. Panorama del derecho penal mexicano. Derecho penal. México: UNAM, McGraw-Hill.

[3] Pérez Moreno Colmenero, Silvia. 2001. Valores para la democracia. Delitos e infracciones administrativas. México: Instituto Nacional para la Educación de los Adultos. 09/13/2024 http://www.oas.org/udse/cd_educacion/cd/Materiales_conevyt/VPLD/delitos.PDF

[4] “Archivo General del Poder Judicial del Estado”. 09/13/2024: https://www.stjsonora.gob.mx/ArchivoPJE/#:~:text=Dentro%20de%20nuestros%20archivos%20se,Estado%20de%20Sonora%20y%20Sinaloa.

[5] “Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en Hermosillo. Ministro José María Ortiz Tirado”. 09/13/2024: https://www.sitios.scjn.gob.mx/casascultura/casas-cultura-juridica/hermosillo-sonora

[6] Leyva Meneses, Hans Ildefonso. 2004. Catálogo para las fuentes documentales de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en el estado de Sonora, serie juicios de amparo, 1900-1917. Tesis de licenciatura. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora. And Barboza Enciso Ulloa, Mayel. 2004. Catálogo del archivo de la Casa de la Cultura Jurídica en el Estado de Sonora del Poder Judicial de la Federación, sección juzgado quinto de distrito del quinto circuito, serie juicios de amparo, 1918-1928. Tesis de licenciatura. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora

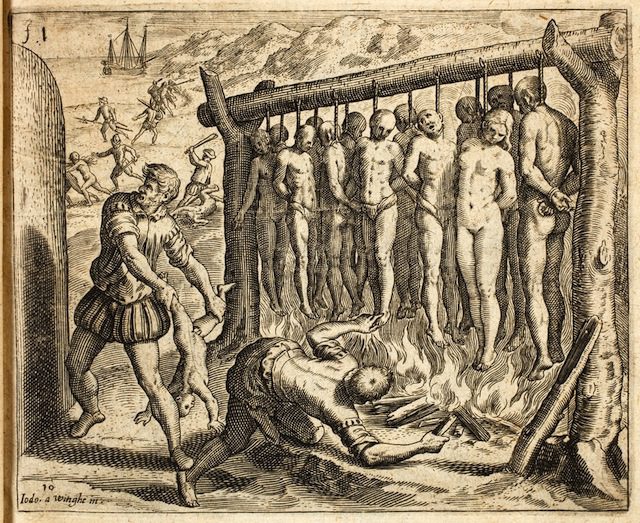

![Description des Indes Occidentales [Description of the West Indies]. Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas. Amsterdam: M. Colin, 1622. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)](http://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/tordes.jpg)