The following narrative is adapted from my recent dissertation on revolutions in Latin America. When I shared it with upper division history students for a class discussion, the story surprised them. Most of them had only ever experienced student government as something to put on your resumé for grad school applications. They had never imagined that student activism could be so decisive for crucial issues of public policy. The Chilean experience seemed to awaken their interest in a rich local legacy of passionate student activism and of unconditional commitment to causes that transcend personal gain. Here I share the story of the bold political style of Luciano Cruz.

As Chile’s first Christian Democratic government attempted to bring social justice through reform during the mid-1960s, medical students in the nation’s second city proposed a more radical change. In a political system designed to concede real power only to the already powerful, they argued, a mere change of government leadership would never suffice. Along with a few disaffected union organizers, the students at the University of Concepción, located in Chile’s second city, formed the Movement of the Revolutionary Left, (MIR), proposing a new constitutional order that, they hoped, would uplift Chile’s perennially poor and underprivileged.

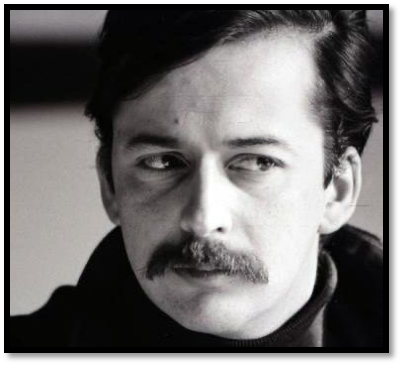

The undisputed leader among the students was the fiery and brilliant Miguel Enríquez, who in 1961, had written on his medical school application essay, “everything has been given to me…, the time has come to give back.” Like Che Guevara before him, the call to heal the sick blended seamlessly with the call to make revolution for the poor. His classmate and best friend, Luciano Cruz, brought a uniquely impulsive energy and irresistible charm to that struggle. The political style of Luciano Cruz allowed him to knew how to rouse, entertain, and impassion any crowd at a moment’s notice.

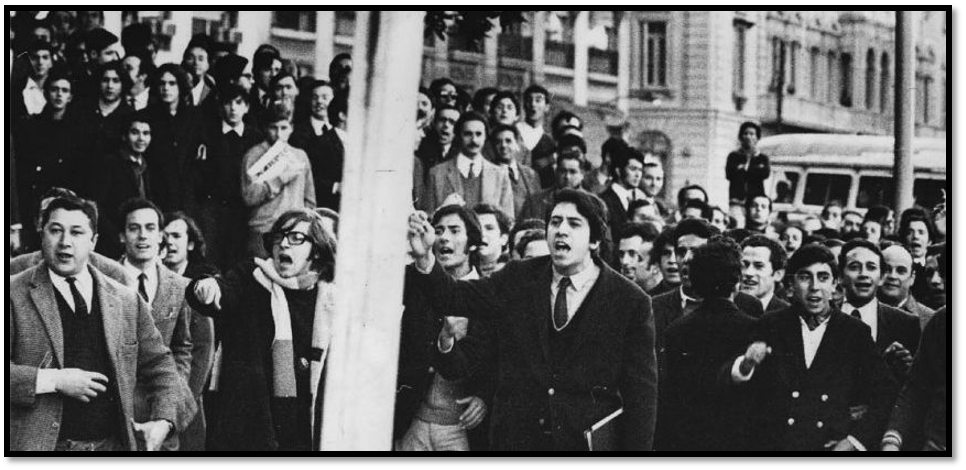

Whereas Enríquez made measured, brilliant speeches—many of which have survived as written documents—his energetic deputy could improvise behind a microphone, holding the multitude spellbound for hours. Historian Marian Schlotterbeck points to Cruz’s debut as a student leader during a 1965 protest of the recent fare increase in public transportation. Chile’s largest labor federation, CUT, (Central Única de Trabajadores), had called for the protest, and they had invited Cruz as one who “embodied the contentious, combative style of the Concepción student movement.” Schlotterbeck points out that there was more at stake than just bus money. “Amidst wild applause,” she writes, “Cruz proclaimed that the demonstrations were no longer about fare hikes but ‘a demonstration by Chile’s poor against the rich.’”[1]

By 1967, Luciano Cruz had set his sights on the presidency of the student federation. The university had reached a crossroads. The Christian Democratic government of Eduardo Frei was promoting university reform on a national scale. Frei’s men had lifted up the University of Concepción as a model. They wanted to restructure higher learning as a driving force for modernization. But members of the newly configured MIR, known as Miristas, understood the plan as an attempt to co-opt and “Americanize” their university. Cruz would become MIR’s candidate to spearhead the resistance.

While technically private, the University of Concepción depended on funding from UNESCO and the Ford Foundation, making it vulnerable to foreign interference in crucial policy decisions.[2] With MIR’s support, the student federation (FEC) demanded the democratization of the power structure so that students and junior professors could have a voice in the decision-making process. But MIR had to win the presidency of the student federation to legitimize its proposal. Focusing his campaign on ideology, class interests, and the social role of the university, Miguel Enríquez had failed in his bid for that office two years earlier. This time, Miguel recognized his classmate’s dynamic advantage. Luciano’s landslide victory in Concepción marked MIR’s arrival as a national political force.

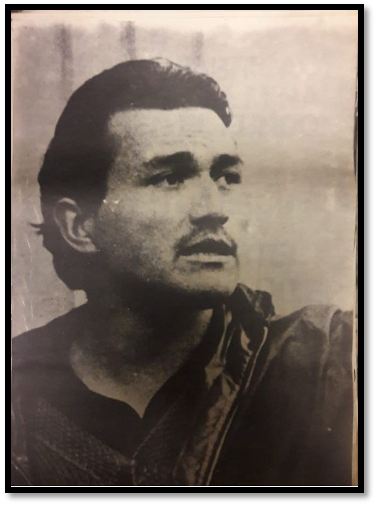

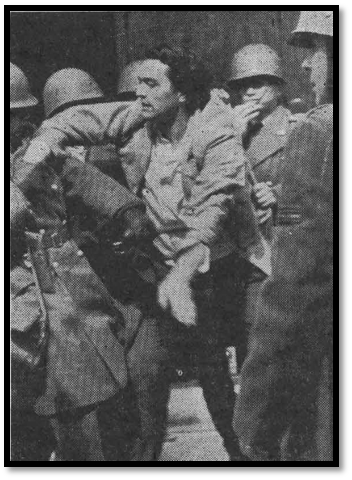

Schlotterbeck highlights a “new brand of audacious student activism” that would predominate in the student federation, transforming university students into political actors on a national scale.[3] Undergrads—and some even younger protestors—made headlines with strikes, street protests, and the occupation of campus buildings. Riot police confronted them with tear gas, truncheons, and water cannons. Jailed students went on hunger strikes, and their objectives began to escalate. Miguel Enríquez called for more than just a university reform. The time had come for a true university revolution. His statement to that effect appeared in the preeminent national magazine of the non-aligned intellectual left, Punto Final, with a photo of Luciano Cruz in a scuffle with five police officers that would become iconic.

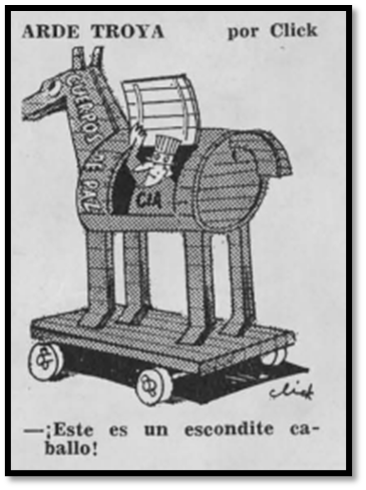

Miguel directed MIR’s leadership to confront the “legal dictatorship” of the current system with relentless combat. They should denounce every detail, he said, so that the forces of repression were compelled not only to cease and desist, but to give ground.[4] On that note, MIR demanded the immediate expulsion of four Peace Corps volunteers from the University of Concepción. Perceived as the youth branch of the dubiously regarded Alliance for Progress, the Peace Corps presence symbolized the imperialist assumptions behind Frei’s model of reform.[5] Students argued that Peace Corps volunteers took up much needed space at the university residence. They also voiced their suspicions (likely credible) that Peace Corps volunteers had provided a stream of inside information to U.S. intelligence services.[6]

While Enríquez focused on the national politics of the reform, Cruz emerged as MIR’s chief tactician and spokesperson. Under his command, at one of their daily demonstrations, students in Concepción abducted a police officer. After holding him hostage in the university for several days, they offered his release in exchange for the same for all the students who had been arrested during recent protests.[7] The symbolic value of that gesture weighed heavily. With it, students reconfigured their recent detentions by Carabineros as similarly random and arbitrary abductions.

Carabineros fought back. They arrested Cruz, and the movement seemed to fall apart until Cruz dramatically escaped from jail and waltzed back into the meeting where student leaders discussed their next move.[8] Although the details of Cruz’ escape remain unclear, his stealth and proficiency in the martial arts seem to have played a part. His return to the front line provided a huge boost for morale, dramatically enhancing his personal mystique and his reputation for dauntless courage and invincibility. It also established MIR’s place in the leadership of the student federation at the Universidad de Concepción (FEC) for the foreseeable future.

But MIR’s ambitions did not stop with the student federation in Concepción. Members of the movement’s inner circle did not want Chileans to think of them as merely the radical fringe of the nation’s restless youth. Aligning themselves with the youthful and dynamic Cuban revolution, Miristas defied the perennial lethargy of Chile’s traditional left to project a hugely inflated image of the new movement’s political significance. Their claim had no real basis in the number of militants, access to material resources, or concrete influence in social organizations, but Mirista leadership bet on the oppressed masses’ perception of their growing visibility as a foreshadowing of an imminent and viable armed revolt. In his incisive analysis of the MIR phenomenon, literary scholar Hernán Vidal observes that MIR’s Comité Central manipulated the obvious contrast between an appearance of mythical power and a reality of tactical impotence, calling it a strategy of “establishing presence.”[9] They didn’t have to really be everywhere; they only had to seem to be everywhere. Luciano Cruz figured as the master of MIR’s expanding illusion of ubiquity.

Until 1969, MIR had mostly operated out in the open. Their practical jokes and disruptions only remained covert until they had succeeded. Then, they generated positive PR. But a pivotal student prank in Concepción would initiate a period of tension between the gregarious publicity that had shaped MIR’s style and method, and a new strategy of strict secrecy. As fate would have it, Luciano Cruz’ impulsive abduction of a local journalist in June of that year provoked the ire of the Frei government, driving the entire movement underground for the first time. Miristas had to learn to hide their militant activities and to use code names. The demands of clandestine living made MIR a more dangerous commitment for new recruits, but it also provided an undeniable aura of romance.

Kidnappings, though frequent, lucrative, and lethal among revolutionary movements in Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina, did not figure in MIR’s habitual playbook. Leaders observed that, in terms of promoting public sympathy for the cause, they usually backfired. But acting independently, Luciano’s regional task force in Concepción crossed the line with a targeted prank in the austral winter of 1969. The Christian Democratic journalist, Hernán Osses Santa María, had lost his job at the University of Concepción because of the reform. He got his revenge by disparaging young Miristas in his editorials. He never criticized their politics. He derided their personal lives, and he made fun of their girlfriends. That seemed to violate an unspoken code of honor. The clever Luciano Cruz decided to teach him a lesson in respect.

Luciano’s team of tricksters abducted Osses Santa María with the archaic idea of tarring and feathering him. Finding no tar, they released him naked in the courtyard of the university during an annual event. There was no real harm done, except to Christian Democratic pride. The Frei government took advantage of the public outcry to invoke a national security statute declaring MIR illegal, and to order the arrest of the Secretary General, along with his wily second in command.[10] That meant that most of MIR’s operatives had to go underground, something Miguel Enríquez had in mind anyway. Cruz had not cleared his plan with the more prudent Enríquez, but his audacity triggered MIR’s rather sudden transition from the gentler politics of campus protests and community organizing to a more decisive program of direct action; most of it, illicit; and some of it, armed. Cleverly-staged bank robberies, framed as Robin Hood style gestures of taking from the rich to benefit the poor, became the order of the day. Ever sensitive to the importance of good publicity, however, the students took precautions to make sure that no one ever got hurt.

After the election of Chile’s first Socialist President, Dr. Salvador Allende, in September of 1970, MIR continued to agitate for faster and more radical reform, but without the emphasis on spectacular disruptions of daily routines. Luciano Cruz took a flat in Santiago, where he conducted a covert program of surveillance, keeping watch over potential coup-plotting generals and their supporters. To this end, he recruited a sizeable contingent of young militants who learned to quietly follow and watch. In that role, Cruz’ team pieced together all the elements of the right-wing attempt to prevent Salvador Allende’s inauguration to the presidency, one that culminated in the assassination of General René Schneider, a trusted army commander.[11] Chilean police investigators, more attuned to internal bureaucracy and protocol than really solving crimes, had failed to break the case, but Cruz’ investigation uncovered embarrassing complicity that reached to the highest levels. Though published in Punto Final, the justice system failed to follow up on his findings.

Luciano Cruz died of accidental gas inhalation in his one-room basement flat in downtown Santiago on August 14, 1971. After he missed an arranged meeting, Miguel Enríquez discovered his friend’s lifeless body. He frantically attempted to revive him, but it was too late. A CIA report surmised that Enríquez might have had Cruz murdered to resolve an internal power struggle.[12] But gas heaters in those days had no safety valves, and Luciano had been complaining of morning headaches for a week. All the witnesses mentioned the smell of gas in the flat. So it was likely careless rather than malicious.

Tens of thousands followed the funeral procession in support of the charismatic Luciano Cruz and the incisive student protest movement he represented.[13] MIR would never be the same without him. But, to this day, Chilean students put their whole heart and soul into their protests.

Nathan Stone, Professor of Instruction at the University of Texas and a recent Ph.D. recipient from the Department of History (2023) of the same institution. His specialization is Modern Latin American revolutionary movements. Previously, he lived and taught in Chile for thirty years, Uruguay for two, and IN Brazil for five. H is fluent in Spanish and Portuguese, and he has published his writing, both academic and non-fiction, in both languages.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Banner image source: http://archivodigital.londres38.cl/index.php/afiche-del-comite-de-solidaridad-luciano-cruz

[1] Marian E. Schlotterbeck, Beyond the Vanguard: Everyday Revolutionaries in Allende’s Chile (Oakland, University of California Press, 2018), 23.

[2] Schlotterbeck, Beyond the Vanguard, (2018), 26; Punto Final, 12, (septiembre 1966), 16-18.

[3] Schlotterbeck, Beyond the Vanguard, (2018), 26.

[4] Punto Final, 40, (oct 1967), 37.

[5] Punto Final, 12, (sept 1966), 18; Punto Final, 37, (sept 1967), 39, and Punto Final, 40, (oct 1967), 36.

[6] Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. (UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 35; and Punto Final, 32, (julio 1967), suplemento, 1-10.

[7] Schlotterbeck, Beyond the Vanguard, (2018), 26.

[8] “La rebelión de la juventud,” in Punto Final, 38, septiembre 1967, 28-30.

[9] Hernán Vidal, Presencia del MIR: 14 Claves Existenciales (Chile, Mosquito Comunicaciones, 1999), 28.

[10] Punto Final, 138, 31 agosto 1971, suplemento, 5.

[11] “El MIR denuncia a los verdaderos culpables del asesinato del General Schneider,” in Punto Final, 117, 10 noviembre 1970, suplemento, 1-10.

[12] CIA, Directorate of Intelligence, 1141-1.37, Confidential, 1 October 1971, declassified September (1999), https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000365918.pdf.

[13] Jorge Müller Silva, “Funerales de Luciano Cruz Aguayo, 16 de agosto de 1971.” First released 1972; remastered by Chilefilms, Santiago, (2014).