When I was very small, I lived six blocks from the Santa Fe Opera. Our home was in the Tesuque Village, which is really just a country road that runs alongside the Tesuque Creek just north of Santa Fe, with twenty tiny cul-de-sacs stretching up into the alluvial crannies of the southern Rockies. There were fruit stands and general stores. The Indians from the Tesuque Reservation would come to trade hides for cigarettes. This was before there were casinos. I remember the taste of the fresh local pears. There will be some in heaven, I assume. Once, I got lost. I was three. An Indian from the reservation took me to every house in the village and asked me, “Is that your house, little boy?”

On the horizon to the east, we had the Sangre de Cristos. They were huge, daunting, legendary and high. Mountain snow accumulated there in the winter to keep the semi-arid New Mexico wasteland inexplicably green all summer. Deep in the heart of the wilderness, at Horsethief Meadow, the early Comanche hid away in the lush green grass of summer with the wild and not-so-wild herds of mustangs that made them the wealthiest traders at the Taos market in the nineteenth century. Savages? Trade in your textbook. They knew more about selective breeding than Her Majesty’s Master of Horses.

To the west, there was the Opera. You might ask why Tesuque had an Opera. All I can say is that it just needed one. It simply couldn’t do without one. It was brand new, when I was three. It went up in 1957. I wasn’t sure where I lived, but I knew it was in the shadow of the Opera, a battleship on our western horizon. Man-made grandeur. And woman-made, of course. A work of art. An open-air theatre, like the Athenians had, long, long ago. A democratic, public forum.

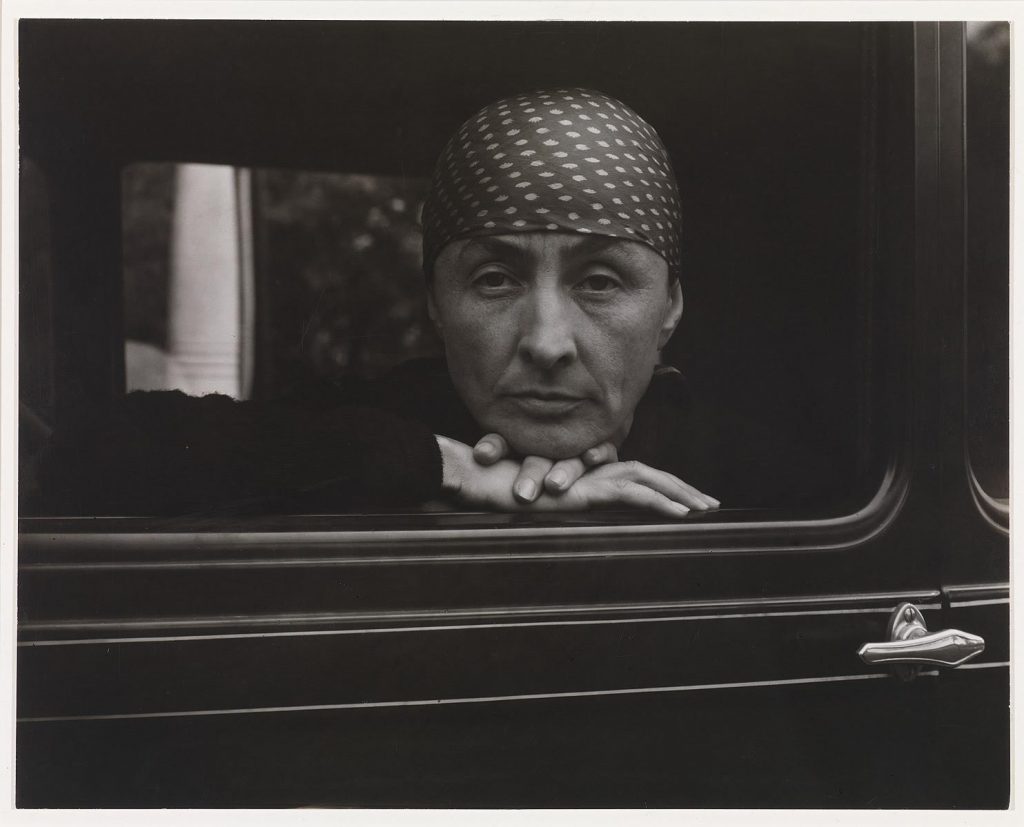

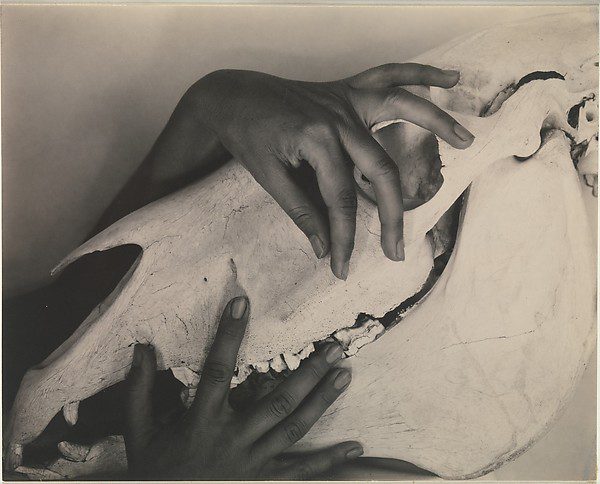

I never went. I was three years old. My brother, one year my senior, and my sister, one year my junior, never went, either. But Momma and Daddy went. (Assuming I got the right house, and they were my real momma and daddy.) Newlyweds, twenty-five years old with three little kids, and walking distance from the Santa Fe Opera. They had season tickets. They were there when an aging Igor Stravinsky conducted his masterpiece, the Rite of Spring. With the New Mexican sunset descending behind the main stage. They were there, in the third row, behind Georgia O’Keeffe, our friend from the Piggly Wiggly in Santa Fe.

We got the LP’s. We just called them records. We played our records one after the other on the old Magnavox Hi-Fi, set into a handcrafted hardwood cabinet, as if that precise technology, the culmination of 1961 electronic genius, was expected to last, unaltered, for two hundred years.

I had to push a stool up to the speaker, so I could reach over to find the switch at the lower right-hand corner of the record changer. Click to the right and click back. Stacked high with Igor’s Rite of Spring, I piled on Sherry Lewis and Lamb Chop, Toscanini’s Beethoven, Belafonte’s Calypso, Walt Disney’s Bambi and the legendary Kingston Trio. I sang with the Kingston Trio one night at a night club in Reynosa. By then, I was four. Walked right across the darkened dance floor all by myself and sat on one of the amplifiers. I knew all the words, and I sang with them, just as I always did. Every day, at home. Of course, they knew who I was. We had sung those songs together hundreds of times. But that is a tale for another day.

Rite of Spring, well, we called it the jungle record, and we hid behind the couch during the rowdy parts. That same year, we got our first Peter, Paul and Mary. The LP. Help me find the way, to the promised land. But, the opera was out of reach. Daddy bought the LP’s for La Traviata, La Bohème, and Madame Butterfly, but he kept them up high and we were down low. It was so we wouldn’t scratch them. And, it was because they were in Italian. And, because they were sad. Too sad for three-year-olds.

I am sixty now. I have been away for a long time. I decided it was time to go back. To go inside the Santa Fe Opera. I bought my ticket online. It was expensive. And I drove two days to get there. I guess, on horseback, it would have been two weeks. Three, by stage coach. Not one to complain.

I wanted Doctor Atomic. It was a contemporary opera sardonically set right there in the New Mexico piñon rattlesnake drylands. The role of Oppenheimer was to be sung by a thermonuclear power tenor. And a healing ceremonial dance by the Navajo and Pueblo nations, on stage, to ward off the bad karma. But it was sold out. Of course, it was. So, I bought Madame Butterfly.

Before you continue, comrade, you should really punch up the famous aria on Spotify or wherever it is you satisfy your musical impulses these days. I don’t know if the María Callas version is on there. She was the diva. It was that good, that night. Sung by Ana María Martínez. Brought the house down. It has been more than a month, and I still cry when I think of it.

It had just rained. A grand New Mexico cloudburst, typical of mid-August. They call it their monsoon. The rain stopped before the curtain opened. Except there is no curtain. Athens, remember? It was cool and damp, though. A Santa Fe night, clouds lifting and the proverbial western sunset, iconic and scented of damp sagebrush, just behind the stage.

You know the melody of the aria. Even if you have never been to the opera. Now, imagine it, there. Cio-Cio San, a.k.a., Madame Butterfly, gazes across the harbor at Nagasaki in 1904. Waiting for her lawfully wedded American imperial husband, Lieutenant Pinkerton, who never took her seriously, to return. Delta Dawn, what’s that flower you got on? Could it be a faded rose from days gone by? Yeah, like that, but, Puccini, comrade. Way cooler. And sadder. The big sad. Still has me choked up.

One day, three years after his departure, a ship does sail into Nagasaki with an American flag on it. Pinkerton has not come to assume his commitment to the delicate Butterfly. He has learned, through the diplomatic gossip network, that he has a Japanese child with blue eyes, that his flesh and blood is descending into poverty and dishonor. Beside the woman he fancied and then, abandoned. Pinkerton has come to take the child away from his mother.

He can’t face her, of course. Too ashamed. Of how he let her down. Of how unremittingly faithful she was, in the face of his own callous indifference.

At the curtain calls, without a curtain, the crowd booed the tenor. Joshua Guerrero. But he was a good sport. He understood. He had portrayed the playboy badass so well that the massive woke Santa Fe audience wouldn’t let him leave the role, not even for the curtain call. Pinkerton had been a world class prick, so his interpreter wasn’t getting a free pass. The listeners’ friendly jeers counted as a standing ovation, for the performer. There was something very wild west, about that. That was rodeo etiquette, comrade, not the Met.

The clincher, that night, was played by a three-year-old. I know this wasn’t in Puccini’s original score. These works are not dead artifacts. They are still alive. After Butterfly commits hara-kiri, Pinkerton arrives to take the boy away to America. The boy, without singing a note (he was really just three years old) wraps himself in the American flag that his mother had used as a curtain in her Japanese-American home in Nagasaki. He picks up the bloodied dagger with which his beautiful mother has just killed herself and, with it, faces down Pinkerton. He is having none of it.

No baby jails. No icy separation from families at borders. No teaching them foreigners a moralistic lesson with heartless biblical puritan cruelty. Cio-Cio San’s boy was only three, but ready to take on the egotistical American imperial madness. If only that gesture could come off the Santa Fe stage, into the real world. Maybe it already has.

Because I am now sixty, and not twenty and not three, I felt that perhaps the central character in the opera was, actually, Suzuki, Butterfly’s servant and companion, the only one who knows her commitment and her suffering, the only one who understands that there cannot possibly be a happy end to this tale. The long night, as Butterfly waits for Pinkerton to arrive, and Suzuki knows that he will most certainly not, was moving. One would hope that she took the boy with her. Somewhere, far away, where his life will be more than the currency of cruel old men and their hateful games.

You May Also Like:

Borderlands Business: Conflict and Cooperation on the U.S. Mexico Border by Anne Martínez

Sanctuary Austin: the 1980s and Today by Edward Shore

Also by Nathan Stone:

The Battle of Chile

The Tiger

Miss O’Keeffe

Underground Santiago: Sweet Waters Grown Salty