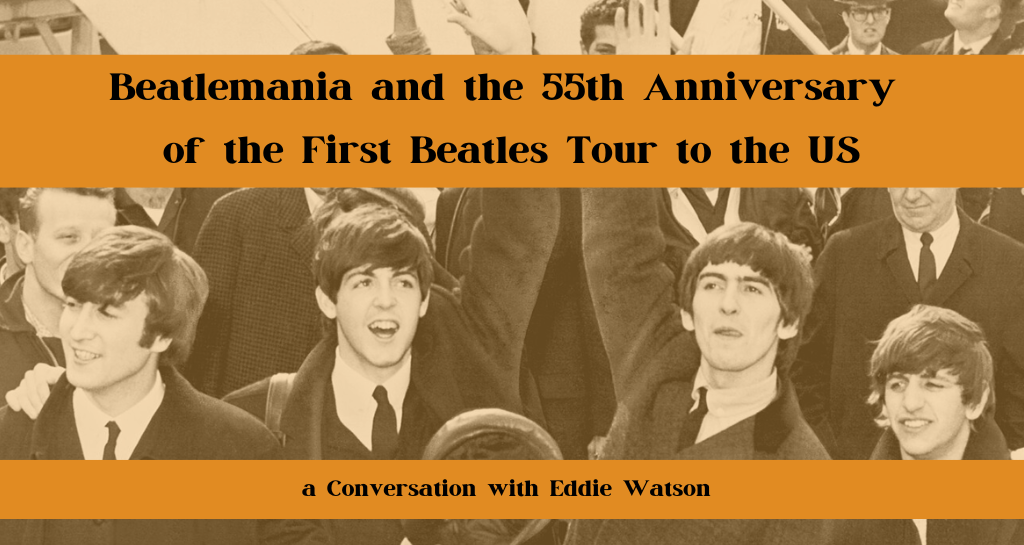

The Beatles arrived for their first concert in the United States on February 11, 1964, to rabid fanfare. Legions of screaming women greeted John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr at every stop of the U.S. tour, leading to observers dubbing the period “Beatlemania.” As one of the most commercially successful and influential musicians of all time, almost every pop music artist cites their influence over their music. Yet who were the Beatles? What was their music like? And why were they so popular?

Ph.D. student in history Eddie Watson and host Augusta Dell’Omo take us deep into the history of the Beatles’ first tour in the United States and reveal why we should understand these popular cultural movements. But, perhaps most importantly, Eddie tells us who is the best Beatle, reveals their greatest hits, and regales us of his own attempt at the Beatle bowl cut.

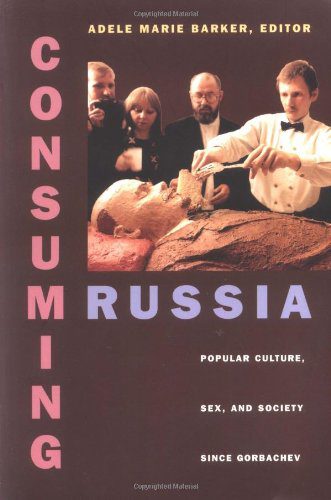

Caught in the middle of this complex maze of post-Soviet change is popular culture, which “finds itself torn between its own heritage and that of the West, between its revulsion with the past and its nostalgic desire to re-create the markers of it, between the lure of the lowbrow and the pressures to return to the elitist prerevolutionary past.” The quest to find, maintain,and alter cultural identity manifests itself in a variety of ways, which accounts for the large scope of this study.

Caught in the middle of this complex maze of post-Soviet change is popular culture, which “finds itself torn between its own heritage and that of the West, between its revulsion with the past and its nostalgic desire to re-create the markers of it, between the lure of the lowbrow and the pressures to return to the elitist prerevolutionary past.” The quest to find, maintain,and alter cultural identity manifests itself in a variety of ways, which accounts for the large scope of this study.