by Laurie Green

April 11, 2017 marks the fiftieth anniversary of a historical moment that is far more relevant today than we might wish: the discovery of hunger in the U.S. or, perhaps better put, the point in the late 1960s when severe poverty and life-threatening malnutrition in the world’s wealthiest nation suddenly soared into public view on the national political stage. This anniversary matters today not only because proposals to restructure federal food programs threaten their very viability, but also because of the role played by the media, then and now.

The very meaning of “discovery,” when it came to the politics of hunger in the late 1960s, rested in part on the production and reception of news, documentaries, visual images, and editorials that, at times, provoked explicit confrontations over who had the right and expertise to say whether starvation existed in America. The one media production that scholars have written about, CBS’s renowned Hunger in America, first broadcast in May 1968 and vividly recalled by many who watched it, is notable as much for the reactions it provoked as its content. Agriculture Secretary Orville Freeman denounced the program’s critique of federal food programs as “biased, one-sided, [and] dishonest.” San Antonio’s county commissioner, A. J. Ploch, reported threats on his life for his statement that Mexican American kids didn’t need to do well in school, for which they needed better nutrition, because they would always be “Indians,” not “chiefs.” Later it came out that the Mississippi congressman who headed the House agricultural appropriations subcommittee borrowed agents from the FBI to track down and survey the cupboards of every interviewee in order to prove the show had been a pack of lies. Drama over who controls truth in the media is not a new phenomenon.

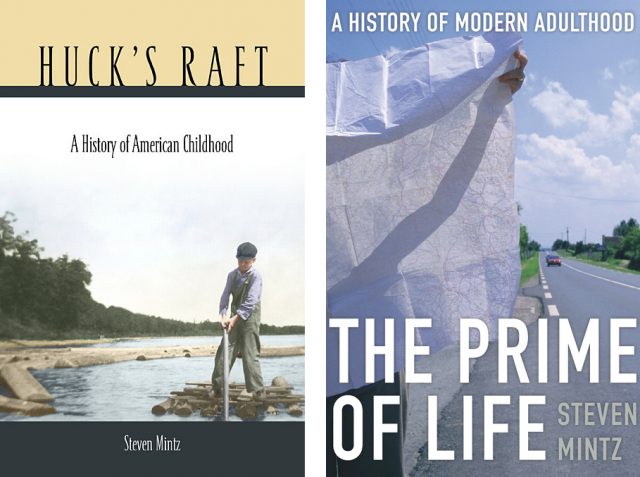

Fannie Lou Hamer speaking at a hearing of Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty in Jackson, Mississippi, on April 10, 1967. Rev. J. C. Killingsworth is seated beside her. (Photograph: Jim Peppler)

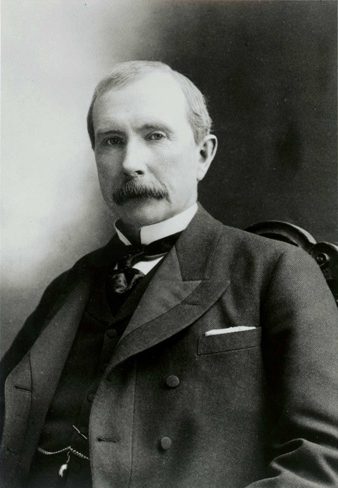

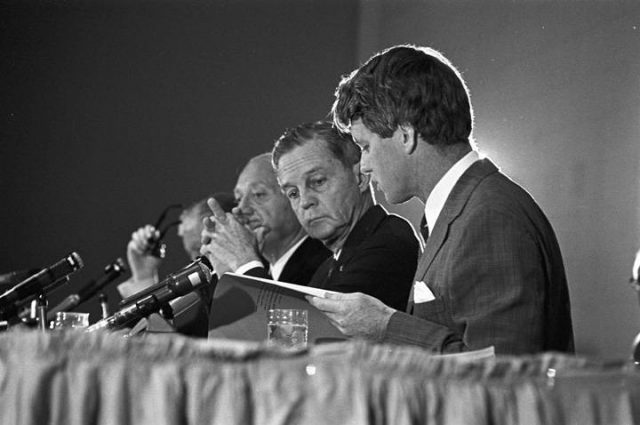

On April 11, 1967, Senators Joseph Clark (D-Pennsylvania) and—famously—Robert Kennedy (D-New York) conducted a daylong tour of the Mississippi Delta that brought them face to face with residents, especially young children, who bore signs of malnutrition so severe that they could only compare them with what they had observed in Latin America and Africa. Their shock at what they witnessed triggered an ultimately victorious decade-long campaign to expand, alter, and establish the federal food programs that are in jeopardy today. Within months, investigations in locales as disparate as Kentucky, San Antonio, and Washington, D.C. precipitated a cascade of further discoveries confirming that hunger was not solely a Mississippi problem.

Senators George Murphy, Jacob Javits, Joseph Clark, and Robert F. Kennedy of the Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Manpower, and Poverty, listening to testimony during a hearing in Jackson, Mississippi, on April 10, 1967 (Photograph: Jim Peppler)

Kennedy and Clark had flown to the Delta from Jackson, where the day before they had heard Mississippi activists testify at a senate hearing on the War on Poverty that starvation had become a genuine threat in their counties. Fannie Lou Hamer, Marian Wright (Edelman)—then an NAACP attorney in Jackson—and others ascribed this devastating situation not only to joblessness caused by cotton mechanization but voting rights repression. County officials, they argued, used government regulations to prevent them from receiving food stamps. Back in Washington two weeks later, Clark, Kennedy, and other members of their committee released a letter they had sent to Lyndon Johnson describing their shock at witnessing malnutrition and hunger among the families they had met and urging him to send emergency food to the area. Johnson denied the request, the press reported, blaming the problem on congressional cuts to the poverty program. Hunger was not new in the U.S., nor had activists previously held their tongues, but now it arrived on the national political stage wrapped in drama and political conflict.

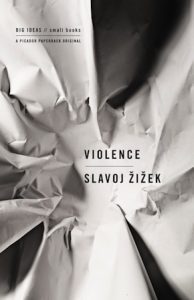

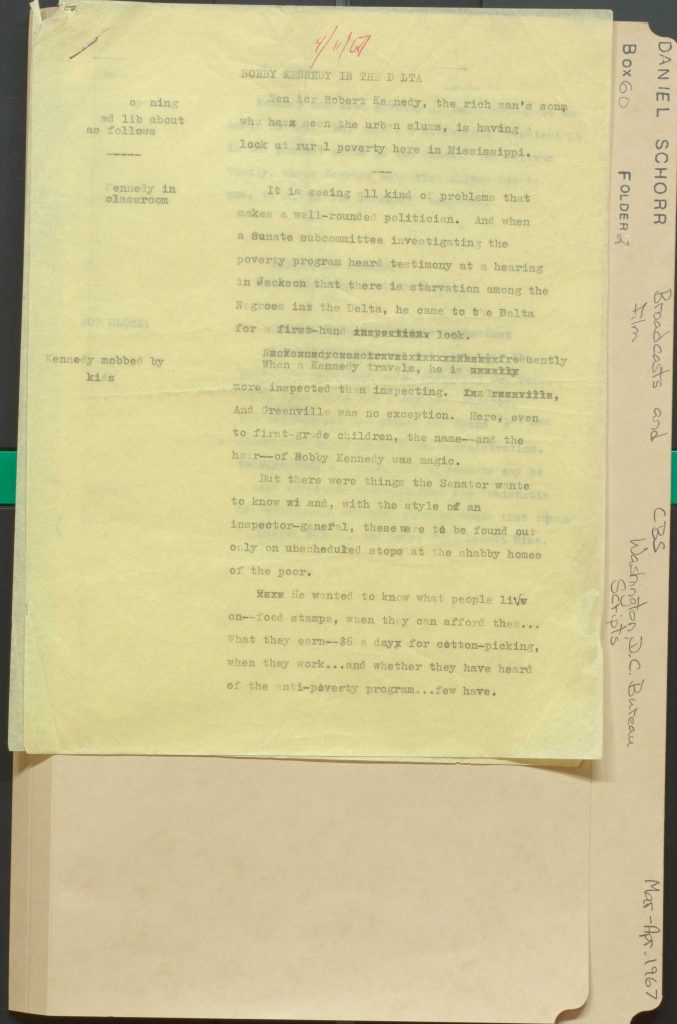

Daniel Schorr’s typescript for CBS News, April 11, 1967. (The Daniel Schorr Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscripts Division)

By evening on April 11, 1967, reporters and photographers had filed stories and images of the senators’ Delta tour. Daniel Schorr’s CBS Evening News report and Joseph Loftus’s New York Times article helped frame what would be cast as ground zero for the politics of hunger. Both portrayed Kennedy surrounded by enthusiastic crowds, but whereas their coverage of the previous day’s hearing had centered on the Mississippi politicians’ assault on Johnson’s War on Poverty, these stories concerned Kennedy and Clark’s critiques of Johnson from the left. Loftus reported that Clark had declined to label what he witnessed as starvation, but asserted that the deplorable conditions indicated the poverty program’s weakness. Schorr mused that RFK might have found a platform other than Vietnam, from which to challenge Johnson.

Schorr began his next report by stating: “Congress talks of poverty and how it should be dealt with, but rarely does it go to look at it.” Clark and Kennedy, however, had gone themselves “to see if the reports of starvation were true.” He described their shock at seeing “children with distended bellies” and speaking with “poor Negroes earning $6 a day for cotton chopping, and many earning nothing.” Many, Clark learned, “could not even scrape together the $2 a month to buy $12 worth of food stamps.” The senators had not spoken of “starvation,” but Schorr had. That term spurred irate Mississippi politicians to launch their own investigations to disprove its existence. Journalist didn’t invent this language—African American activists in Mississippi did that; however, they helped create the context for national controversy.

Simeon Booker covered similar ground in his article for Jet, aimed at black readers, but he made Kennedy and Clark’s Delta tour inseparable from what occurred at the hearing the previous day. This strategy allowed him to present a trenchant critique of racism in the antipoverty program from the vantage point of activists at the hearing. At a time when some journalists had begun to separate hunger from other problems the hearings had addressed, Booker took a different tack, beginning and ending with Kennedy’s responses to witnessing hunger and malnutrition but diving into economic, medical, and political challenges in between.

Others pursued feature stories that combined “behind-the-scenes” investigation, vivid language, and political insight. Robert Sherrill’s June 4 New York Times essay, “It Isn’t True That Nobody Starves In America,” took readers to Alabama and Mississippi, while slamming the beltway politicians who had structured federal food programs such that they could produce starvation as easily as nutrition. Mississippi could pride itself on having food stamp programs in more counties than elsewhere in the South, he declared, but purchase requirements meant that the poorer one was, the more unlikely one was to access benefits. Sherrill minced no words, criticizing even Kennedy for using euphemisms like “extreme hunger.”

Sherrill’s article preceded national hearings on hunger and malnutrition that Clark’s Senate poverty committee held in Washington in July 1967. People watched the hearings on television or read reports of such moments as when Senator John Stennis lit into North Carolina pediatrician and civil rights activist Raymond Wheeler. Wheeler was one of six doctors sent by the Field Foundation to investigate starvation in Mississippi and had accused white elites of trying to starve blacks out of the state. Stennis, who had his own radio program and was well aware that cameras were rolling and reporters were scribbling, accused him of “gross libel and slander.”

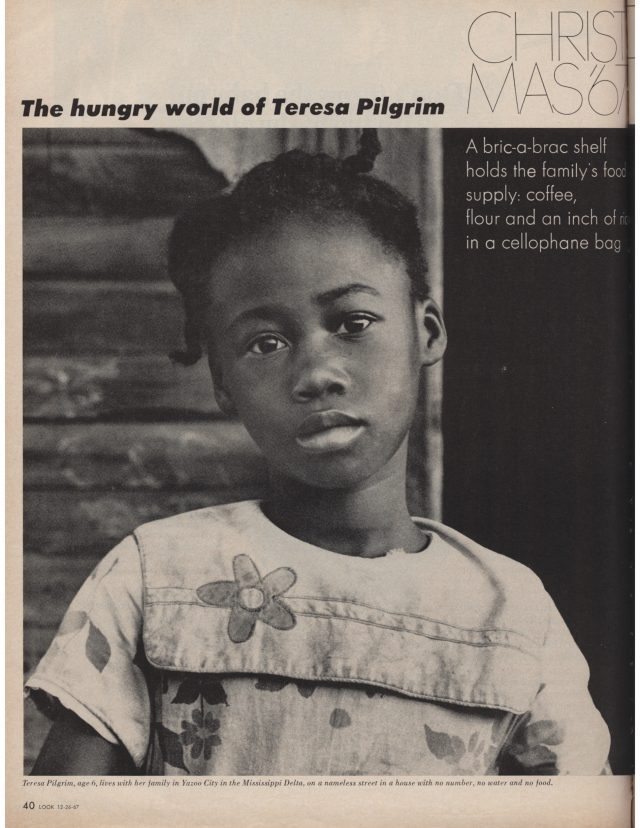

Questions of proof inspired one of the most intimate and widely-read features to appear in a mass-circulation glossy magazine, Al Clayton and William Hedgepeth’s “The Hungry World of Teresa Pilgrim,” which ran in LOOK’s Christmas 1967 issue. Struck by Clayton’s photographs, which Kennedy displayed at the hearings as proof of starvation, Hedgepeth teamed up with the photographer for a story about a family surviving conditions the senators described. Both white southerners — Clayton from southeast Tennessee, Hedgepeth from Atlanta — they spent days with the Pilgrims, especially with six-year-old, bright-eyed Teresa, whose photograph opens the story. Public response was off the charts for LOOK, as readers asked where to send Christmas gifts and money.

CBS’s phones began ringing off the hook five months later, even before the broadcast of Hunger in America had concluded. Viewers not only sent food and financial support to those who appeared in it, but sent letters to their representatives demanding the overhaul of food programs that the documentary prescribed. While the Federal Communications Commission weighed charges that CBS had overstepped the ethical bounds of journalism, social commentators referred to the documentary as the turning point in bringing public awareness to the crisis of hunger.

The matter of truth, including who had the right to define it, was an incendiary one in April 1967 and for months thereafter. “Starvation,” unlike either hunger or malnutrition, implied that someone or something was responsible, raising the stakes in a conflict that drew in large swaths of the public via the media. Two years later, antipoverty activists in every region were fed up with hearings and investigations; they wanted change.

![]()

Also by Laurie Green on Not Even Past:

Women’s March, Like Many Before It, Struggles for Unity.

1863 in 1963.

Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600 – 2000.

![]()