This article is reposted from Russian History Blog.

This blog post is inspired by petty anger. In this deeply weird and unsettling time, I am, like virtually everyone, staying at home. I am in almost every way lucky—I have a job (though hoo boy do I sometimes wish I had listened to my gut and not said yes to being department chair), I have a comfortable home, our restrictions are not too extreme. I live alone, which on balance right now feels like probably also a lucky thing, though it has its own stresses and sources of sadness. I’ve in particular come to rely on a daily walk to get out into the air, to stretch my legs, to try to turn off from all the stresses of my job right now.

On these walks, though, I often find myself seething with rage at the pettiest of things—people who do not keep to the right while walking or riding or running. Even in a time of social distancing, my rage feels out of proportion to the offense. But then I remembered a letter of complaint I came across in one of my beloved files of random correspondence from the Gatchina Palace administration [Gatchina Palace was built near St. Petersburg in the 18th century for a favorite of the Russian Empress, Catherine the Great].

To His Excellency, the Director of the Gatchina Palace Administration

Riding yesterday, the 3rd of August [1892], at 9 in the evening, on a bicycle, in the Imperial Priorate Park, I came upon a gentleman unknown to me, driving a white trotter at full speed, who, despite my increasingly ringing my bell, continued to ride on the left side of the road, as a result of which I, at risk of being trampled, was forced to jump down from my bicycle onto the grass; at my comment, made in the most polite form, that one should drive on the right side, the gentleman sitting in the charabanc and driving the horse answered me with unacceptable obscenity. On my way back, about twenty minutes later, I had the misfortune to again come across this same gentleman, continuing as before to drive on the left side of the road; in response to my bell and to my comment that besides the existing rule to drive on the right side, even only politeness demands that one should give way, the gentleman informed me that such a rule does not exist, having added along with this message personally to me insulting expressions so impolite, that repeating them word for word in the present letter I consider impossible; in the end of all of this insulting actions were threatened. Of all of this I immediately gave a report to the duty officer of the Gatchina Police. [Hearing] my description of the characteristics of the horse and the gentleman, the Police officers sitting in the duty room recognized the owner of the horse as Gatchina homeowner Bronislav Liudvigovich Adamovich; in order to definitively establish the identity of the culprit, I gave the Police a detailed description.

Having in mind that a simple monetary penalty such as laying a fine by judicial process will hardly guarantee that the public visiting the Imperial Priorate Park [will not be bothered by] a repetition of such misconduct on the part of the above mentioned gentleman, [misconduct that] violates social morality and order in the Imperial park, and that the insult given by him to me was without any reason on my part, I have the honor to present all above noted to the discretion and resultant decision of Your Excellence, humbly asking that you inform me of what is done about this matter.

Collegiate Secretary

Feodor Feodorovich Rein.

4 August 1892

Someone looked into the matter the day it was sent, and noted down the following report:

Feodor Feodorovich Rein, Collegiate Secretary, works as a Secretary of the Main Military-Sanitary Committee of the Ministry of War. Residence: in the town of Gatchina, on Baggovutovskaia ulitsa, no. 46, the home of engineer Rein.

I have the honor to report … that in the matter of the offenses committed in the Priorate Park by nobleman Bronislav Liudvigovich Adamovich to Collegiate Secretary Fedor Fedorovich Rein, a witness statement by Luga meshchanin Artur Karlov Reikhenberg, residing in the village Bol’shaia Zagvozdka, Gatchina township, explains that it was completely possible for Rein to pass without obstruction along the road on the right side, and beside that it is necessary for all bicyclists to pull over and get off their bicycles when they meet people riding on horses in light of the fact that every horse seeing the unfamiliar sight of a bicycle without fail begins to buck and to shy and in general to sidle, so for Rein to be offended by Adamovich there is no foundation, all the more so because, as Reikhenberg reports, Rein was the first to address Adamovich in rude form, with the comment “you do not know how you should drive, why don’t you keep to the right side,” but all the same from my point of view Adamovich should be given proper warning that he should drive more calmly, and that if there is a second complaint about him driving quickly and not following the general rules of driving, then he will be prohibited from driving in the Priorate Park forever and for reckless driving in general he will face legal liability.

I’m not going to try to spin this out too much—of course, there’s plenty of stuff to say about these figures and who they might be, or of the fact that Mr. Rein was a thoroughly modern man on his bicycle in 1892. Perhaps I’ll come back to them in another post at some point. But I copied this all out because I thought it was sort of funny, and I loved the resonance of the idea of bicyclists and drivers at odds over road usage, because that’s still such a present part of urban discourse.

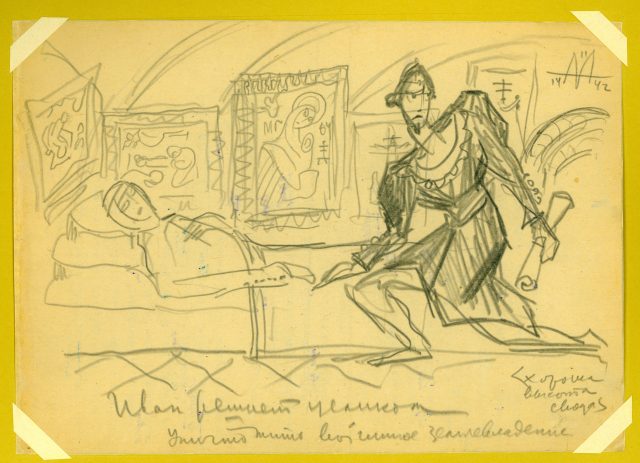

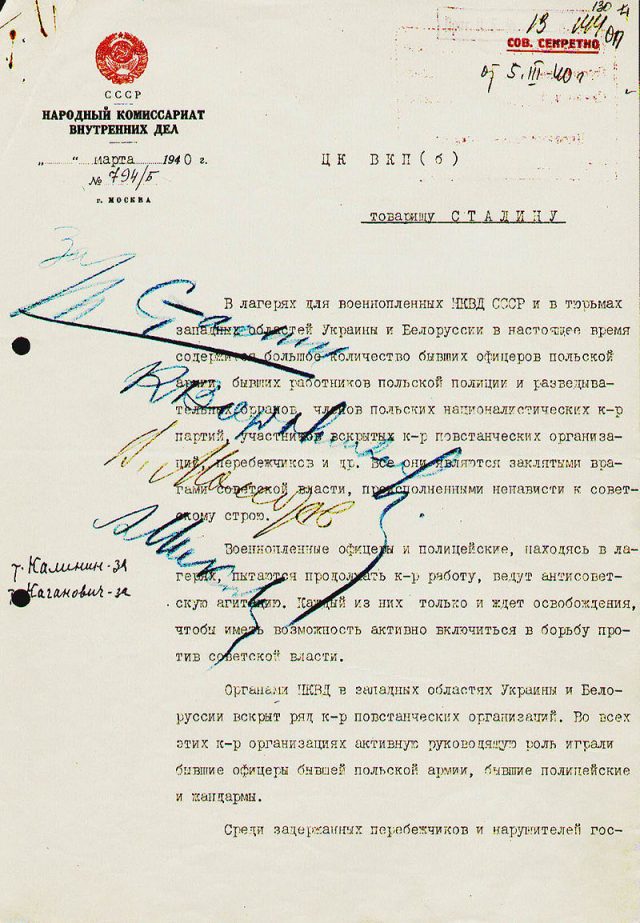

Image of a bicycle from B. Kaul’fus, Kratkoe rukovodstvo k izucheniiu ezdy na velocipede i obrashcheiiu svelosipedami fabric Adamants Opelia v Riussel’sgeime (Kiev, 1893)

Now, though, I’m struck by the anger. The anger that seemed to motivate Rein—if Reikhenberg was right and he really did have enough space, his action to jump down into the grass feels like a bit of a conscious display of being inconvenienced for the sake of show, rather than anything real—the anger he received in return—although Reikhenberg reported that Rein was the first person to be rude, his reported statement (which, I should note, used the proper vy, not the familiar and potentially offensive ty) hardly seems to be enough to cause someone to respond with obscenity.

In 1892 Gatchina was a bustling place, with Alexander III often in residence (though probably not in August) and its two railway lines making it an increasingly desirable suburban residence for people who worked in St. Petersburg. The park might simply have been busier than normal with summer dacha residents, making the whole exercise of bicycling or driving more frustrating. I suppose one could also make a case that the quickness to anger on the part of these men reflects the internal opposition they might have felt about their own status as modern men—one a nobleman (probably a Polish nobleman) with a fancy horse, one with cutting edge bicycle—in an anti-modern system, an anti-modern system that could not be ignored at that time and in that place because it was centered on the palace next to the park.

And then I think about my own petty anger, and wonder about which of the many background worries we all face right now that is manifesting itself in those feelings of rage.Sources:

RGIA [Russian State Historical Archive) f. 491, op. 3, d. 386, ll. 311-312ob.

You might also like:

A Deportation Story: Russia 1914

Free Healthcare with a Price

Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy”

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.