By Mark Sheaves

Not Even Past has published many feature articles, book and film reviews, and podcasts on slavery and its legacy in the USA. The history of slavery is an important issue today, and the articles we publish aim to make publicly available the academic research and historical perspectives on this topic produced by graduate students and faculty at UT Austin. This body of work provides an overview of key issues important for anyone wanting to understand slavery and its legacy in the USA.

How has slavery shaped racial politics today? What was it like to be a slave? How different was the experience of slavery on plantations and in cities? Was the Emancipation Proclamation successful? How has slavery been portrayed in popular culture? Can slavery be mapped? Below you will find a thematic list of articles we have published offering some answers to these key questions.

Race and slavery’s lasting legacy:

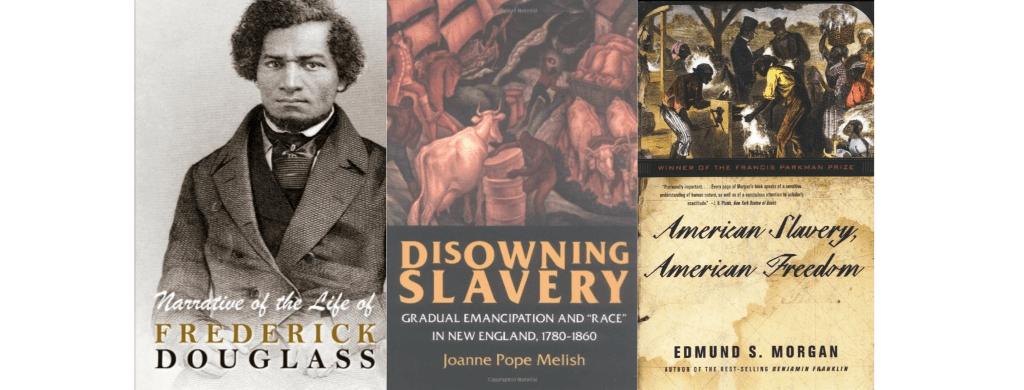

Jacqueline Jones discusses her book A Dreadful Deceit: The Myth of Race from the Colonial Era to Obama’s America, an exploration of the way that the idea of race has been used and abused in American history.

Daina Ramey Berry and Jennifer L. Morgan offer historical perspectives on the casual killing of Eric Garner, highlighting slavery’s lasting legacy and the historical value of black life.

Concerned by misconceptions about slavery in public debate, Daina Ramey Berry dispels four common myths about slavery in America.

Urban Slavery:

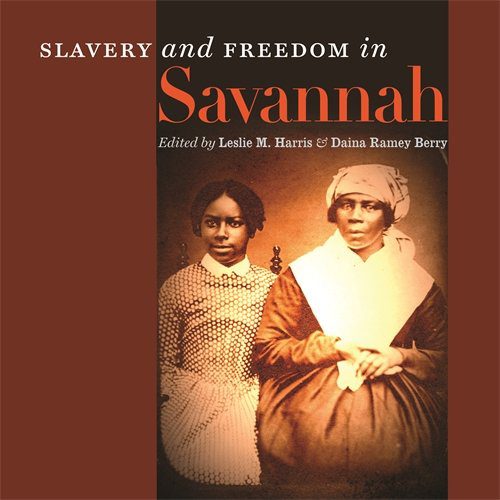

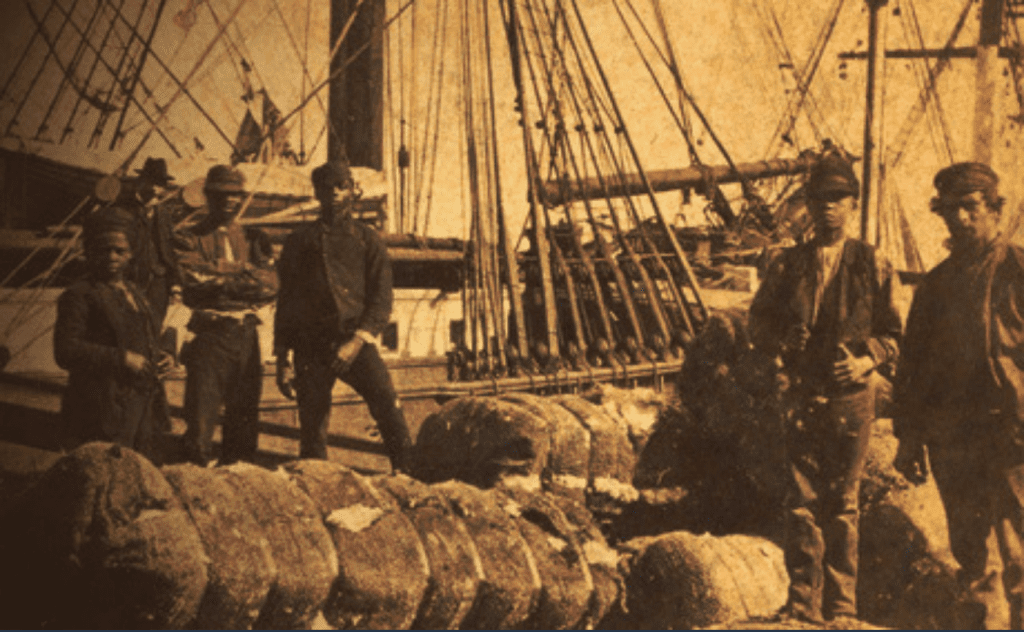

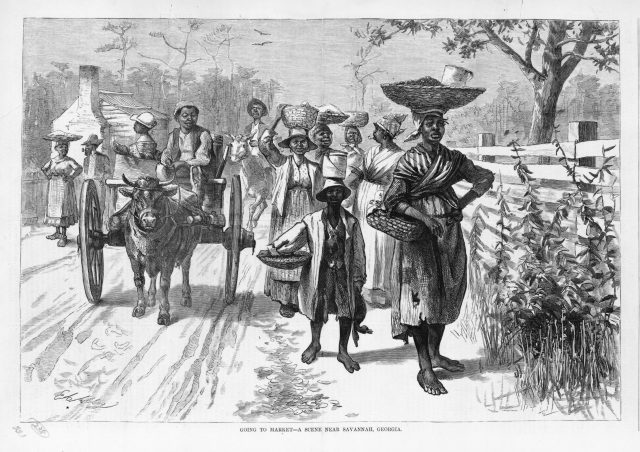

In their article Slavery and Freedom in Savannah, Leslie M. Harris and Daina Ramey Berry explain the importance of understanding urban slavery: “Because of the great economic and social dominance of rural plantation-based slavery in the Americas, historians have long assumed that slave labor was not suited to cities and therefore slavery in American cities was insignificant. But a re-examination of slavery in cities throughout the Atlantic World has demonstrated the importance of urban areas to the slave economy and the adaptability of slave labor and slave ownership to metropolitan regions, especially port cities such as Savannah. Urban slavery was part of, not exceptional to, the slave-based economies of North America and the Atlantic world.”

Interested to learn more about urban slavery? You may also like:

Jacqueline Jones discusses her book Saving Savannah: The City and the Civil War, a study of the unanticipated consequences of the Civil War for Confederate slaveholders and the dramatic efforts of the city’s black people to live life on their own terms in Savannah.

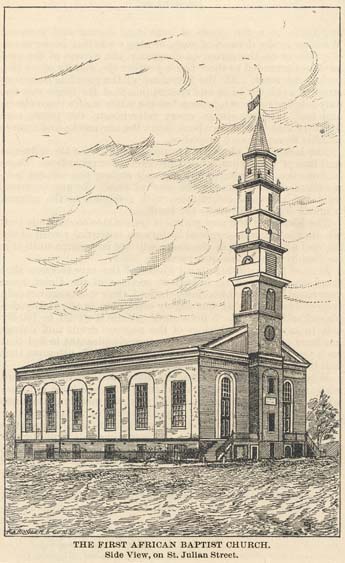

Tania Sammons’ essay on Andrew Cox Marshall, a former slave who went on to become a successful businessman and religious leader in pre-Civil War period Savannah.

From 15 Minute History, Daina Ramey Berry talks about Urban Slavery in the Antebellum U.S.

Daina Ramey Berry and Leslie Harris offer further reading recommendations on Urban Slavery.

Experiencing Slavery:

Slavery is often discussed in terms of numbers and dates, human rights abuses, and its lasting impact on society. To be sure, these are all important aspects to understand, but one thing that is often given relatively short shrift is what it was like to actually be a slave. What were the sensory experiences of slaves on a daily basis? How can we dig deeper into understanding the lives of slaves and understand the institution as a whole?

On 15 Minute History, Daina Ramey Berry discusses teaching the “senses of slavery,” a teaching tool that taps into the senses in order to connect to one of the most important eras in US history and bring it to the present

You may also like:

Let the Enslaved Testify: Daina Ramey Berry discusses the use of former slave narratives as a “valid” historical source.

Labor and Gender:

Daina Ramey Berry discusses her book Swing the Sickle, an incisive look into the plantation lives of enslaved women and men in antebellum Georgia.

For further reading, consult this list of classic studies, new works and a few novels on labor and gender and the institutions of slavery in the United States.

Emancipation Proclamation:

On the afternoon of January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation, freeing approximately three million people held in bondage in the rebel states of the Confederacy. The Emancipation Proclamation was a huge step towards rectifying the atrocity of institutionalized slavery in the United States, but it was only one step and it had a mixed legacy, as these essays by UT Austin historians remind us.

George Forgie discusses the political wrangling that accompanied the Emancipation Proclamation, the work it left undone, and the need – that seems so obvious today, but was so deeply contested at the time – for a law abolishing slavery altogether.

Jacqueline Jones takes us right into Savannah’s African American community on New Year’s Eve, to see and hear how Black Americans there anticipated the momentous news.

Laurie Green brings us up to 1963 to show us how civil rights activists in the 1960s saw the work of the Emancipation Proclamation as still unfinished. One hundred years after it was signed, they viewed the civil rights movement as an effort to fulfill its original intent to bring not only legal freedom, but economic justice and individual dignity to the descendants of US slaves.

Daina Ramey Berry looks at Quentin Tarantino’s sensationalist and willfully inaccurate treatment of slavery in Django Unchained and she offers us alternative sources for learning about the historical violent abuses of slave life.

Juliet E. K. Walker examines the contrast between the legal and economic consequences of the Emancipation Proclamation.

You might also like:

Jacqueline Jones on The Freedmen’s Bureau: Work After Emancipation

Henry Wiencek recommends Eric Foner’s The Fiery Trial

Slavery in Popular Culture:

Historical films and books always distort the historical record for dramatic purposes. Sometimes that doesn’t matter and sometimes it does. How has the history of slavery been presented in historical films?

Jermaine Thibodeaux reviews 12 Years a Slave (2013) and talks about the difficulty of dramatizing the ‘Peculiar Institution’.

Daina Ramey Berry, Tiffany Gill, and The Associate of Black Women Historians comment on The Help (2011).

Nicholas Roland offers historical perspectives on Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012).

Daina Ramey Berry and Jermaine Thibodeaux discuss Nat Turner: A Troublesome Property (2002) and Haile Gerima’s film Sankofa (1993)

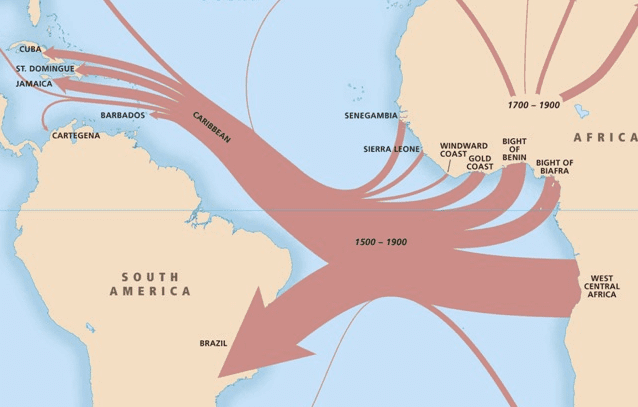

Mapping Slavery:

Henry Wiencek recommends two significant digitalization projects that help capture broad trends related to slavery and emancipation in the US:

Mapping the Slave Trade using Emory University’s Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.

Visualising Emancipation(s)‘, a new digital project from the University of Richmond that maps the messy, regionally dispersed and violent process of ending slavery in America.

First photo via The Texas Tribune