We knowed freedom was on us, but we didn’t know what was to come with it. Wethought we was going to get rich like the white folks. We thought we was going tobe richer than the white folks, ‘cause we was stronger and knowed how to work, andthe whites didn’t, and they didn’t have us to work for them any more. But it didn’tturn out that way. We soon found out that freedom could make folks proud, but itdidn’t make them rich.

–Texas slave-born Felix Hayward, 1937

Plantation slavery was the nation’s most profitable enterprise before the Civil War and, with the onset of military hostilities, White America, southerners as well as northerners, businessmen and the working class, hoped the institution could be preserved, but only where it existed. Slavery had proved profitable not only to a slave-holding oligarchy in the South but also to northern business interests in banking, transportation, shipping, insurance, investment and manufacturing. In the North, moreover, not only the white urban working class but also small businesspeople depended on profits from the processing, sale and transportation of slave-produced commodities for their economic livelihood.

Indeed, until the Civil War, slave produced cotton comprised more than 50% of America’s exports and was the basis of the nation’s wealth. White America profited from this race-based institution of forced unpaid slavery, the engine of enterprise that propelled the nation’s pre-Civil War, pre-industrial economy. Moreover, the results of America’s first modern war were transformative. The nation emerged from the war, subsequently building on an unprecedented profitable economic foundation derived from its newly developing military industrial complex.

Yet, for African Americans, while a de jure freedom would be accomplished with the three Civil War Amendments in 1865, 1868 and 1870, the historical reality was the continuation of a de facto subordinate status of racial inequalities. For African Americans in the march from slavery to freedom, significantly, racial economic iniquities persisted, even after the Civil Rights Acts of the 1960s and well into the twenty-first century.

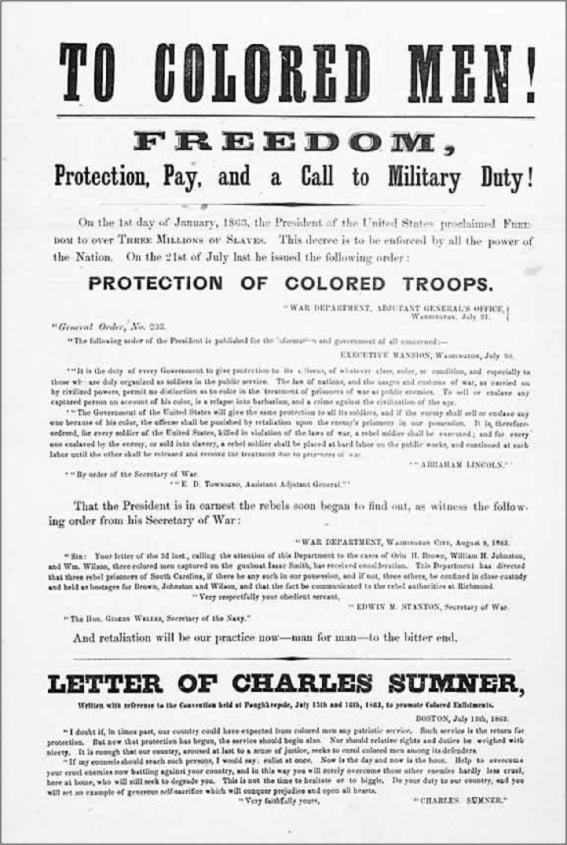

Initially, on April 15, 1861, in response to the Confederate firing on Fort Sumter, President Lincoln called for 75,000 new enlistees in the Union Army to shore up its then military force of only 16,000, but with unanticipated Confederate victories the first year of the war, more Union troops were needed. Even so, Lincoln’s call for 300,000 volunteers in July 1862 yielded only 88,000 new recruits. How could the Union win a war without a substantial military force that could defeat the Confederacy? Fear of the destruction of slavery, however, was the Confederate’s Achilles heel and, as a matter of military necessity, Lincoln capitalized on this fear with his preliminary draft of the Emancipation Proclamation.

When presented to his cabinet in July 1862 Lincoln, however, was advised by Secretary of War William Steward to wait until the Union won a significant battle before making a public announcement. On September 22, 1862, five days after the first major Union victory at Antietam September 17, 1862, Lincoln officially announced his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. And, the document, indeed, was as much a matter of military necessity as it was an “act of justice,” especially when Lincoln proclaimed that on January 1, 1863 slaves in the states of rebellion would be free. As he stated: “[U]pon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”

On January 1, 1863, the eleven-state Confederacy, obstinately prepared to defend to death the institution of slavery, did not withdraw from the war. The Supreme Commander of Union military forces, equally determined that the nation would be preserved, gave up any public political pretense of winning the hearts and minds of Americans who supported the Confederacy. Yet, prospects of slave emancipation also heightened fears of the northern white working classes. In the New England, Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern states, whites comprised over 98% of the population. Yet, fear of some four million slaves, 14% of the American population, flocking to the North to take their jobs and hold down wages, simply put, was not the kind of incentive white workers needed as a basis to fight a war.

For the northern white laboring classes slave emancipation, it seemed, would work to their economic disadvantage, unless the entire black population could be removed from the nation. Consequently, President Lincoln attempted to mitigate concerns of the white laboring class. Just one month before the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect Lincoln announced in a speech made on December 1, 1862 that, while the Emancipation Proclamation would free slaves in the states of rebellion, the possibility existed that, with a Union military victory, the colonization of all blacks could be accomplished thereby eliminating the threat of job competition.

According to Carl Sandburg in his Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, as Lincoln explained: “Reduce the supply of black labor by colonizing the black laborers out of the country, and by precisely so much you increase the demand for, and the wages of, white labor.” So, while the white working class in the North, potential recruits for the Union Army, would not be enthusiastic about fighting a war to bring down slavery, doubtless, they would support a war where a Union victory might lead to the complete removal of the nation’s black population, both slave and free.

Throughout the war, the President’s continued support of black colonization also underscores the extent to which the Union’s Commander-in-Chief’s priority, “preserving the union,” took precedent, even if meant that the only free people in America would be those who were white. Indeed, in a New York Times review of William Miller’s Lincoln’s Virtues, historian Eric Foner proffered an analysis suggesting that: “Lincoln’s support of a policy [colonization] that might be called the ethnic cleansing of America was no transitory fancy.” Moreover, as historian Charles Wesley noted, even during the final month of the war, when Lincoln supported the idea of granting some deserving blacks the right to vote, he also continued to support colonization.

Consequently, Lincoln’s December 1862 Colonization edict, preceding his Emancipation Proclamation, which stipulated that slaves in the state of rebellion would be free on January 1, 1863, were brilliant strategies of military necessity. If the Confederacy withdrew from the war, the institution of slavery would be preserved. If the Union won and Lincoln followed through on black colonization, not only northern white workingmen, but also the southern white working class would not have to compete for jobs with some 4.5 million free blacks. What else could the “Great Emancipator” do? To win a war, he needed an army and the masses of men who could fight in the Union army were the white workers.

Even so, as Lincoln was drafting the Proclamation in the summer of 1862, Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, published an open letter on August 19, 1862 to the President. Entitled “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” Greeley pleaded to the President to free the slaves, emphasizing that slave emancipation would weaken the Confederacy. Responding in a letter written August 22 Lincoln wrote:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union, . . . I have here stated my purpose according to my view of Official duty: and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

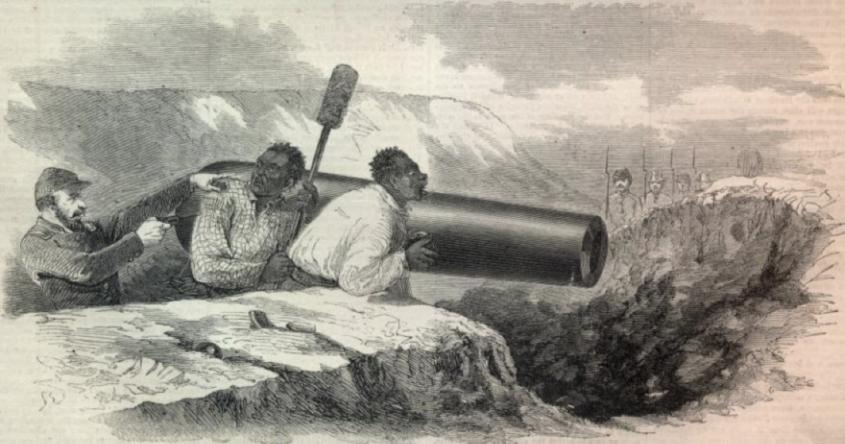

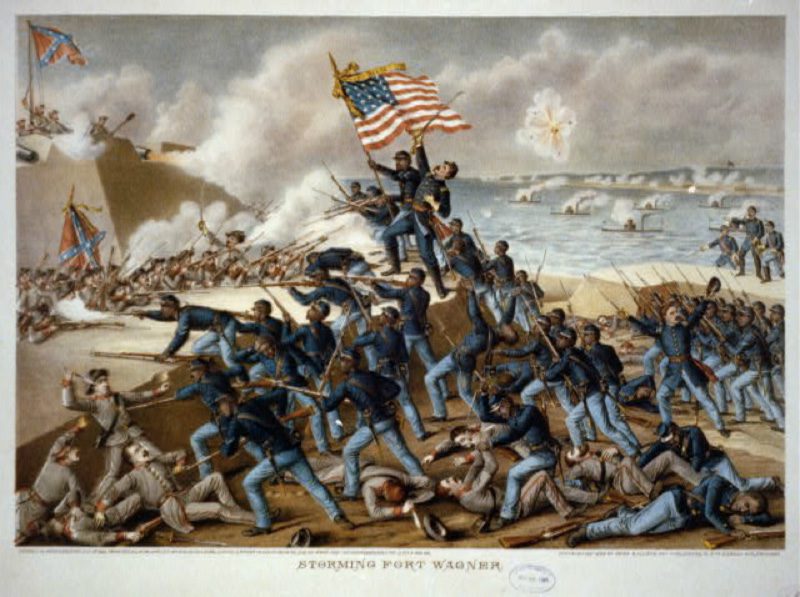

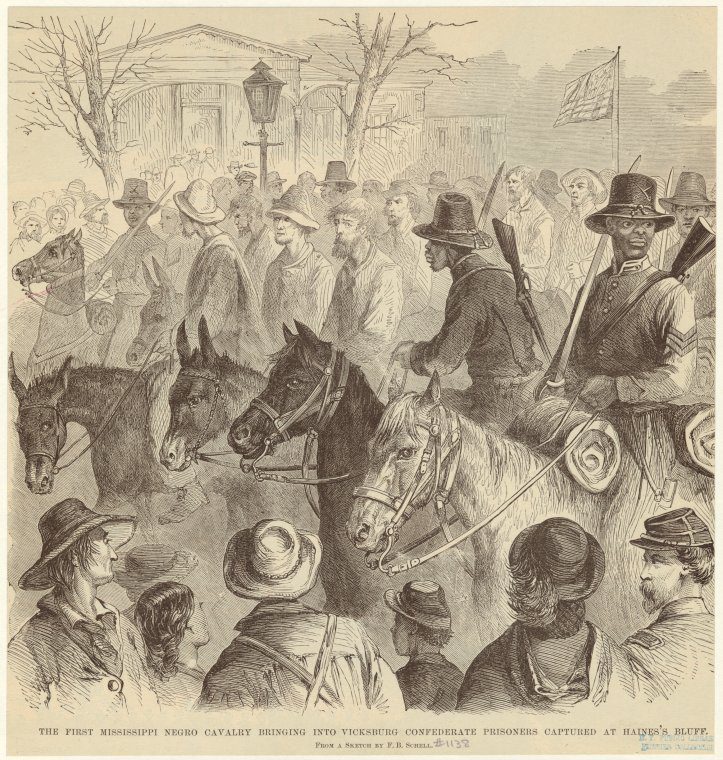

While Lincoln could personally wish that “all men everywhere could be free,” as President, his priority was to save the Union. Whether blacks were slaves or free or, even if it meant the complete removal and colonization of all blacks, the Union would be preserved! More than 100,000 slaves came under Union control as contraband. Also, a significant number of blacks who comprised the 180,000 United States Colored Troops (USCT) were former slaves. Their enlistment was encouraged in the Emancipation Proclamation for Lincoln stated: “And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

Still, over 3 million Blacks remained in bondage during the Civil War. The experiences of those who came under control of Union forces during the Civil War is instructive of the prospect for their economic advancement. Historian Willie Lee Rose reviewed the life of contraband freedmen in Union occupied Port Royal, South Carolina during and after the Civil War as a “Rehearsal for Reconstruction.” When Union military troops occupied the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina in 1861, white plantation slave owners fled, abandoning their property, including some 10,000 slaves. They remained and worked the confiscated lands, growing cotton as well as their own crops for sale. Profits enabled some to purchase land, but in 1865 the new President Andrew Johnson returned the land to the former owners.

Yet, the virulent urban race riots that took place in the North during the 1850s ”Decade of Crisis” as well as on the northern home front during the Civil War, provide a more prescient prelude for the post-Civil War Black American’s search for economic freedom. From the end of the Civil War through the post-Civil Rights era, racial intolerance and racial violence as well as the persistent unconscionable economic and societal subordination of African Americans persisted. In many ways, then, the race-based labor conflicts that took place during the Civil War and the exclusion of blacks as skilled and even unskilled laborers in the manufacturing sector of the North’s incipient military-industrial complex presaged what would be the reality of life for urban blacks in post-Civil War industrial America.

Ultimately, as William E. B. Du Bois noted in his 1903 The Souls of Black Folk: “To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.” Indeed, those who were horrified by media presentations of New Orleans refugee blacks in the 2005 Katrina disaster found little that distinguished their economic suffering from that of black refugees during the Civil War in their efforts to escape the devastating effects of slavery. Still, the Emancipation Proclamation provided the basis for the beginning of freedom for African Americans. Particularly in the twenty-first century, the 2008 election and 2012 re-election of the first African American president of the United States, Barack Obama, contributed to the pride of Black Americans, as an acknowledgment of their freedom. But as Texas slave-born Felix Hayward said in 1937, “We soon found out that freedom could make folks proud, but it didn’t make them rich.”

Still, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation that began as a “matter of military necessity” marked the beginning of an “Act of Justice” by the President as he pursued full constitutional sanction to end the inexorably unconscionable institution of the forced unpaid servitude of black people held as slaves. In 1864 President Abraham Lincoln, “the Great Emancipator,” took leadership in securing constitutional sanction for the freedom of blacks from slavery, achieved with the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Yet, some 150 years after the document went into effect and despite the access of African Americans to leading national political positions, full racial equality, particularly the end of race-based economic iniquities, has yet to be achieved. Perhaps, by January 1, 2113?

You may also enjoy:

George Forgie, “Work Left Undone: Emancipation was not Abolition”

Jacqueline Jones, “The Emancipation Proclamation reaches Savannah”

Laurie Green, “1863 in 1963”

Daina Ramey Berry, “‘Unmixed Blessin’? A Historian’s Thoughts on Django Unchained”

Nicholas Roland, “A Historian Views Spielberg’s Lincoln (2012)”

Further Readings:

Lerone Bennett, Forced Into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream (2000).

Mary Frances Berry, Military Necessity And Civil Rights Policy Black Citizenship and the Constitution, 1861-1868 (1977).

John Hope Franklin, The Emancipation Proclamation (1963).

Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America (2004).

Harold Holzer, Edna Greene Medford and Frank J. Williams, The Emancipation Proclamation: Three Views (2006).

James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (1992).

William Lee Miller, Lincoln’s Virtues: An Ethical Biography (2002).

Benjamin Quarles, Lincoln and the Negro (1962).

Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln – the War Years (1941).

Juliet E. K. Walker, The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship, Vol 1 (2009).