by Huaiyin Li

This book reconstructs the history of the Ye family beginning in the fifteenth century, when its first ancestor was recorded, all the way to the present. The focus of the book is on Ye Kunhou and his son in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and on the Ye brothers (Kunhou’s great great grandsons), who experienced the turbulence of war and revolution under the Republic, and took different paths after the Communist Revolution in 1949. The author’s father-in-law, Ye Duzhang, is one of the key protagonists of the family’s history, which gave Esherick access to a variety of personal sources, including family genealogies, memorials, biographies, poems. memoirs, oral histories, and Ye Duzhang’s personal dossier.

The focus of the book is on Ye Kunhou and his son in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and on the Ye brothers (Kunhou’s great great grandsons), who experienced the turbulence of war and revolution under the Republic, and took different paths after the Communist Revolution in 1949. The author’s father-in-law, Ye Duzhang, is one of the key protagonists of the family’s history, which gave Esherick access to a variety of personal sources, including family genealogies, memorials, biographies, poems. memoirs, oral histories, and Ye Duzhang’s personal dossier.

The book is divided into three parts, to cover the imperial, the Republic, and the People’s Republic periods. The surviving genealogies and Kunhou’s volumes of poems illustrate the ways that the Ye ancestors regulated the family by adhering to Confucian mores and conventions, such as filial piety to parents, fraternity among brothers, harmony with neighbors, eschewing involvement with the local authorities and educating boys in Confucian teachings to prepare for the civil service examination. What is particularly interesting in this part is the impressive success of Kunhou and other Ye men of his time in moving up the ladder of the imperial bureaucracy in the nineteenth century. Beginning with the position of a magistrate candidate, Kunhou advanced to the ranks of prefect and circuit intendant, owing to his ability to assist provincial governors in supervising water-control projects and providing logistic service in suppressing the Nian bandits. His two brothers served a county magistrate and a prefect, respectively. His son, Boying, began with a purchased position in the Board of Reveue and eventually escalated to the position of governor, thus surpassing his father’s rank. Surprisingly, none of the Ye men ever passed the civil service exam beyond the initial levels for a degree to qualify them as upper-gentry members. Critical to their successes was the protection they received from the key figures in the military and civil bureaucracy. These patronage networks, as Esherick notes, reflect the overall deterioration of the regular bureaucracy in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Part II begins with an examination of the life of Kunhous’ great grandson, Chongzhi, a banker in Tianjin under the aegis of the famous industrialist Zhou Xuexi in the early Republic and then centers on Chongzhi’s children. Unlike the daughters of the Ye family who received no school education (except for the fifth) and later had unhappy arranged marriages, the ten surviving sons all attended the elite Nankai Middle School. Here Esherick observes an interesting distinction among the sons of different ages. The three older sons followed a conservative pattern of serving family interests, in Chongzhi’s banking business in Tianjin or going into business shortly after graduating from college and they all stick with the loveless marriages prepared by their parents.

In sharp contrast, the younger boys were “born to rebel.” They each had a love marriage of their own choice and they participated in student movements, either against the Japanese invasion or in the Nationalist government’s non-resistance policy. Two of them eventually became members of the Communist Party, enduring the subsequent hardship and personal sacrifice in wartime. One became so troublesome he was expelled from the family and ended up as a comedian who would not resume contact with his brothers for decades. A noticeable exception was the seventh son, who pursued an academic career in China and the U.S., and eventually returned to the New China in 1950 after receiving his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago despite a well-paid job available to him in the U.S. The younger Ye brothers’ life stories are revealing. What drove them to join the CCP or return to China, as Esherick points out, was not their faith in communism but their discontent with the corruption and dictatorship of the Nationalist regime and their idealist dedication to the cause of national salvation and betterment.

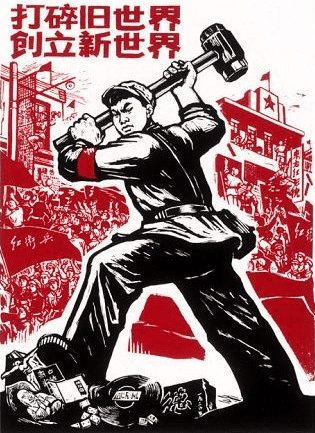

Part III traces the Ye brothers’ family life and political career after 1949. Two of the brothers were victims of the Party’s repeated political campaigns that aimed to tame the liberal intellectuals. They both had to endlessly confess their “wrongs” for befriending or collaborating with Americans in China before 1949 and for criticizing local Party leaders in the 1950s. Both were classified as “rightists,” losing their jobs and even being divorced or alienated by family members. The Cultural Revolution beginning in 1966 turned out to be disaster to all of the Ye brothers. Not only were the two rightist brothers arrested and imprisoned on the charge of being American spies, but the other two brothers, who had joined the CCP before 1949 and served as high-ranking government or party officials in the 1950s and 1960s, were also attacked by Red Guards as “capitalist power holders” and exiled to the countryside for political reeducation. The seventh brother, an American trained scientist, was labeled as a reactionary “academic authority.” They would not be rehabilitated until the early 1970s with the reversal of the radicalism of the Cultural Revolution.

Weaving the vicissitudes of an elite urban family with the turbulence of the entire nation in the past centuries, Esherick presents in this book an exceptionally rich and authentic picture of the Ye men and women experiencing family life, education, government service, local politics, and nationwide movements. Unparalleled in the study of family history in modern China, it will be of interest to all readers interested in China.

You may also like:

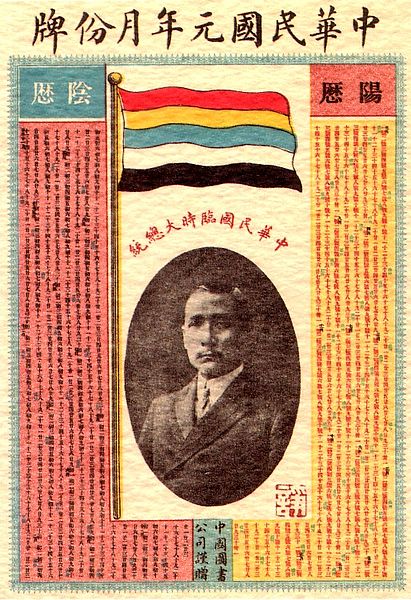

Our review of “The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China.”

Pearl Buck’s Nobel Prize winning book “The Good Earth.”

Photo credits:

All images courtesy of Wikiemedia Commons

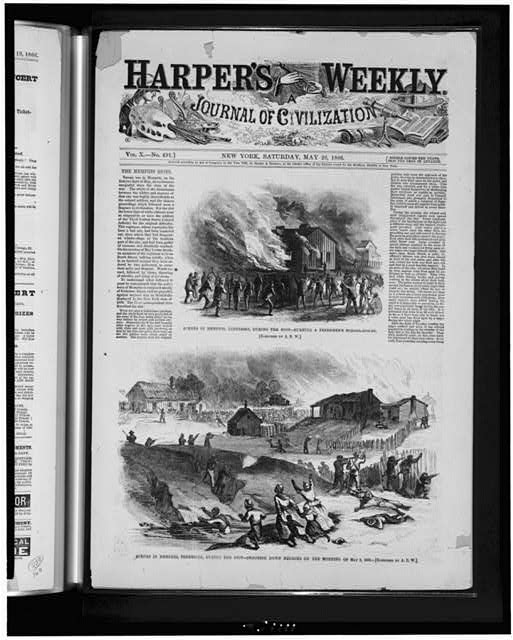

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as

It places gender in the context of the roles of the church and the paternalistic factory owners as well as the memories of the workers, to tell this history of forgotten myths and morals in the workplace. Dulcinea in the Factory shows that male factory owners, managers, and church officials saw themselves as

In Besieged: Voices from Delhi 1857, Mahmood Farooqui draws on more than ten thousand Urdu and Persian documents processed by the rebel administration and later used by the British as evidence in Bahadur Shah Zafar’s trial. As Farooqui notes in the introduction, despite the widespread availability of histories, memoires, and essays on the 1857 uprising, we know much about the British experience and remarkably little about what went on within the walls of the seized city. The documents in this collection show how the rebel government administered the city and how the uprising affected ordinary people.

In Besieged: Voices from Delhi 1857, Mahmood Farooqui draws on more than ten thousand Urdu and Persian documents processed by the rebel administration and later used by the British as evidence in Bahadur Shah Zafar’s trial. As Farooqui notes in the introduction, despite the widespread availability of histories, memoires, and essays on the 1857 uprising, we know much about the British experience and remarkably little about what went on within the walls of the seized city. The documents in this collection show how the rebel government administered the city and how the uprising affected ordinary people. In the prologue, Mitchell explains, “No longer divided into categories of ‘free’ or ‘slave,’ people of African descent acted upon assumptions that the race was unified, that institution building was possible, that progress was imminent.” This optimism shaped ideas about collective identity, destiny, and improvement of the race.

In the prologue, Mitchell explains, “No longer divided into categories of ‘free’ or ‘slave,’ people of African descent acted upon assumptions that the race was unified, that institution building was possible, that progress was imminent.” This optimism shaped ideas about collective identity, destiny, and improvement of the race.