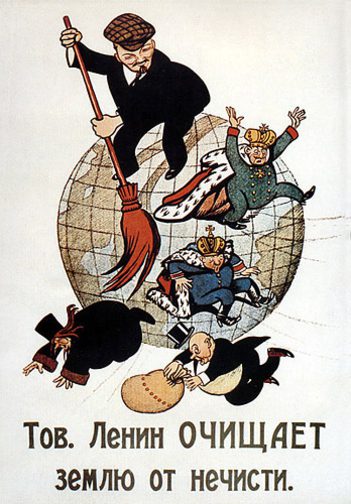

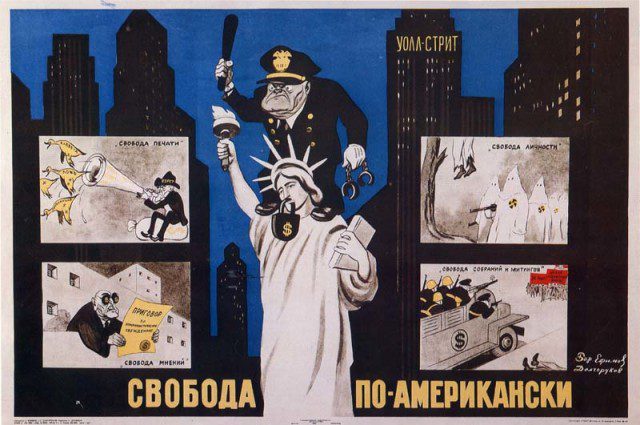

During the early 1960s American Jews began realizing the severity of the anti-Semitic policies under which the 3 million Jews in the Soviet Union were living. This sparked an organized effort across American Jewish communities to raise awareness about the human rights violations being faced by Soviet Jews. Throughout the decade the White House frequently received letters from Jewish organizations and leaders requesting that the President use his influence to persuade the Soviets to rethink their anti-Semitic policies. Jewish organizations also wrote directly to the Soviet government pleading for it to ease its discriminatory policies targeted at Jewish culture and religious practices. Letters sent to the Kremlin were often asking the Soviet government to merely follow its own laws, citing cultural freedom as a right that was granted to all Soviet citizens in the 1917 Declaration of Rights. Another common request sent to the Soviet government was that Soviet Jews, who had been separated from family members as a result of the Holocaust, be allowed to reunite. Many organizations, especially those with an underlying Zionist agenda, used such arguments with the Soviets (and the White House) in hopes that it would provide a convincing pretense for a mass emigration of Soviet Jews to Israel.

In response to Zionist efforts to use the discrimination of Jews in the Soviet Union as an opportunity to increase the population of Israel, Jewish anti-Zionists leaders began writing to the White House expressing their concerns. During his time in office, President Johnson, a strong and vocal supporter of Jewish causes, received numerous letters from anti-Zionist rabbis and Jewish organizations asking him to take their views and solutions into consideration. These letters were primarily aimed at explaining to the Johnson administration that Zionism is not synonymous with Judaism, thus supporting a Zionist approach in the Soviet Union should not be thought of as supporting a Jewish approach. These letters often point out that the vast majority of the American Jewish community at that time was either not supportive of the Zionist movement or outright anti-Zionist.

One letter in particular, sent to President Johnson by The American Council For Judaism, an organization of Anti-Zionist, reform rabbis, was quite explicit in expressing opposition to Zionism. In this letter the Council attempts to draw the White House’s attention to the fact that Zionism is not the humanitarian rescuing of the Jews, nor should it be viewed as a movement that is particularly inline with the tenets of Judaism as a religion. The letter explains to the president that, from the Council’s perspective, the aim of Zionism is not to create a Jewish state, but a Zionist state, emphasizing ethnicity over religion.

The letter goes on to point out that Zionists have worked hard to make it so that criticism of Israel (especially by non-Jews) has become synonymous with criticism of Jews as a whole, and sometimes unjustly labeled anti-Semitism. According to the Council this is an intentional way to not only deflect criticisms of Zionist ideologies, but also to make criticism of the State of Israel and its legitimacy completely off limits. As a result of this, many American Jews and non-Jews shied away from speaking out against the Johnson administrations’ whole hearted support of Zionism and the solutions it offered in efforts to ease the plight of Soviet Jews.

As the decade progressed, Jewish special interest groups would continue to work with the White House in the battle to end the state imposed hardships on Soviet Jewry. Ultimately the Israeli voice would prevail, and during the 1970’s a noticeable trickle of Soviets emigrants to Israel would begin. This is perhaps to be expected, as every Prime Minister Israel has ever had was either born in the Russian Empire or born to parents born in the Russian Empire, thus the connection to the region’s Jewish population runs deep among Israel’s elites. Over the next several decades more than a million Jews would leave the USSR (and the post-Soviet territories) to settle in Israel.

The documents cited in the essay are held in the LBJ Library and Museum, “White House Central File; RM (Religious Matters) Box #7. They include a letter from the American Council For Judaism to Jack Valentini on December 18,1963, a letter from the American Council For Judaism to President Johnson on January 25, 1967, a letter from the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America to Bill Moyers on December 8, 1966, a letter from Richard Korn (president of the American Council For Judaism) to President Johnson on June 16,1966, and a letter from the Satmar Rebbe Joel Teitelbaum and Rabbi S. A. Berkowits to President Johnson on September 23,1966.