In 1963 Jalal Al-e Ahmad, accompanied by his wife, the renowned Iranian novelist, Simin Daneshvar, traveled to Israel as an official guest of the country. He later wrote a travelogue about the journey, published in Iran under the title, Safr beh vilayet esrail (Journey to the Land of Israel). Two years earlier the author had gained his leftist internationalist credentials when he published one of the most important Third World manifestos, known as “Gharbzadegi” (Plague from the West). Al-e Ahmad is perceived to have laid the intellectual and ideological foundations of the 1979 revolution in Iran; both the leader of the Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and Iran’s current Supreme Leader considered Al-e Ahmad to be an influence and role model. This article reviews the most recent translation of Al-e Ahmad’s travelogue, and will be useful to anyone wants to know more about modern Iran.

Translator Samuel Thrope’s introduction allows the reader to understand the profound complexity that characterized Al-e Ahmad throughout his career. Thrope provides excellent biographical and historical contextualization of the text. He also confronts one of the profound dilemmas confronting Al-e Ahmad’s reader. The use of Vilayet in the title can be translated in two different ways. One is charged with religious meaning as “Guardianship of Israel,” while the second carries the more prosaic meaning of Territory. As the travelogue itself makes clear, Al-e Ahmad himself was divided about Israel’s role in that land.

Translator Samuel Thrope’s introduction allows the reader to understand the profound complexity that characterized Al-e Ahmad throughout his career. Thrope provides excellent biographical and historical contextualization of the text. He also confronts one of the profound dilemmas confronting Al-e Ahmad’s reader. The use of Vilayet in the title can be translated in two different ways. One is charged with religious meaning as “Guardianship of Israel,” while the second carries the more prosaic meaning of Territory. As the travelogue itself makes clear, Al-e Ahmad himself was divided about Israel’s role in that land.

Like a large section of the Iranian left, Al-e Ahmad viewed Israel as part of the Third World. Al-e Ahmad juxtaposes East versus West and draws the borders of the East from “Tel Aviv to Tokyo,” acknowledging Israel’s ability to create an indigenous culture (unlike in Iran, as he analyzed in Gharbzadegi), that did not blindly mimic other cultures but was based on the ancient Hebraic Jewish culture. Al-e Ahmad was especially impressed with the revival of the Hebrew language. His admiration for almost everything he saw in Israel, did not prevent him from arguing that the Palestinians, and by extension the East in general and the Arabs and Muslims in particular, paid the price for the sins committed by Europeans in the Holocaust.

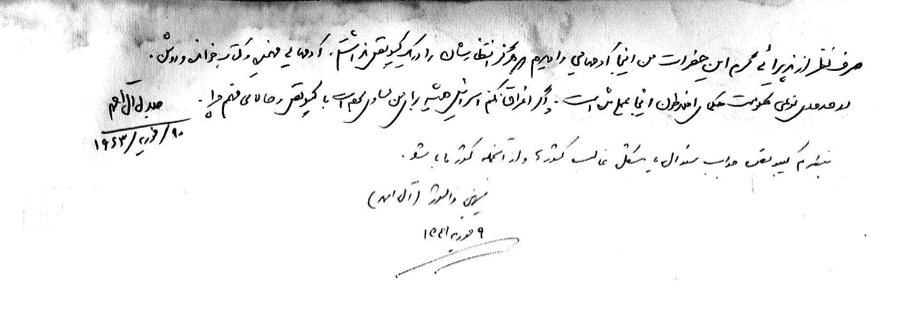

Al-e Ahmad and Daneshvar spent some time in the north Israel kibbutz “Ayelet Ha’Shahar,” which allowed the couple to get a first hand experience of kibbutz life. They saw a play, hung out with kibbutz members, and immersed themselves in conversations about China, the USSR, and Cuba over glasses of beer. Just before leaving, Al-e Ahmad wrote in the kibbutz guest book: “not only were they hospitable, but I met people here that I never expected to meet. Learned people, understanding and open-minded. In a sense, they are implementing Plato. Honestly speaking, I always identified Israel with the Kibbutz, and now I understand why.” Simin Daneshvar added: “as I see it the Kibbutz is the answer to the problem of all the countries, including our own.

Al-e Ahmad and Daneshvar spent some time in the north Israel kibbutz “Ayelet Ha’Shahar,” which allowed the couple to get a first hand experience of kibbutz life. They saw a play, hung out with kibbutz members, and immersed themselves in conversations about China, the USSR, and Cuba over glasses of beer. Just before leaving, Al-e Ahmad wrote in the kibbutz guest book: “not only were they hospitable, but I met people here that I never expected to meet. Learned people, understanding and open-minded. In a sense, they are implementing Plato. Honestly speaking, I always identified Israel with the Kibbutz, and now I understand why.” Simin Daneshvar added: “as I see it the Kibbutz is the answer to the problem of all the countries, including our own.

This text opens a window to the mindset of the Iranian left. Al-e Ahmad’s praise of Israel articulates his (and other Iranians’) dispute with the Arabs, his harsh criticism of Arab governments, and refutes Arab ideas about Iran’s inferiority.

The last chapter of the travelogue shifts tone and criticizes Israel for abandoning its Third World position and becoming a colonial power in its own right. The origin of the chapter is the subject of some controversy. Some believe that it was written in 1968 after the 1967 war and just before Al-e Ahmad’s death (in 1969), and reflects his own and the Iranian left’s disillusion with Israel. During the 1967 war, when Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights and then imposed military control over the entire population of non-citizen Palestinians., it became impossible for observers like Al-e Ahmad to view it as a nation that had taken part in a postcolonial struggle. The other explanation is that after his death, this chapter was written by his brother, Shams Al-e Ahmad, in order to get it approved in the radical revolutionary circles, for publication in Iran in 1984. Thrope adds some useful comments about this controversy as well. Thrope’s suggests that it was Jalal Al-e Ahmad himself who wrote this chapter, and that the voice expressed there is one of a literary character (a friend who wrote a letter to Al-e Ahmad). By presenting this fictional dialogue, Al-e Ahmad contemplates his ambiguous stand towards Israel and Zionism, or as Thrope writes: “Could Zionism really serve as a model for the remedy that Iran required? Just as importantly, as a Muslim, an Easterner, and an intellectual opposed to the Shah’s policies, which included close relationship with Israel, how should he relate to the Jewish State’s existence in the heart of the Muslim Middle East?” In this chapter, Al-e Ahmad not only criticized Israel as a colonial power, he harshly criticized the European intellectual left and singled it out for what he sees as double standards. While they vehemently fought against the colonization of Algiers and were outspoken in their criticism of the colonial project as a whole, they could live peacefully with the colonization of the territories gained by Israel in 1967. Al-e Ahmad blames Jean-Paul Sartre and Claude Lanzmann for leading this dreadful trend. He also blames the military regimes of the Arab countries for their incompetence in facing the changing reality of Israeli policy, and the “Petrodollar Empires” of the Persian Gulf for myopic political and economic goals in only caring about the oil industry.

Jalal Al-e Ahmad (r) with his wife, writer and intellectual Simin Daneshvar (l), in an undated photograph (probably from the early 1960s).

This book recounts a fascinating journey undertaken by an Iranian intellectual to an Israel that existed primarily in the author’s mind. The kind of utopia Al-e Ahmad saw would strike many Israelis as odd. Yet, I am sure that every reader would find this book (and its excellent translation) to be a window on the prerevolutionary Iranian left at a time when it was possible for an Iranian intellectual to embrace certain aspects of Israeli society; to get a glimpse of the history of the Israel-Iran relations and the greater Middle East too.

Listen to an interview with translator Samuel Thrope on 15 Minute History

Image of kibbutz guest book reproduced with the kind assistance of archivist Noa Herman at the archive of Kibbutz Ayelet Ha’Shahar.

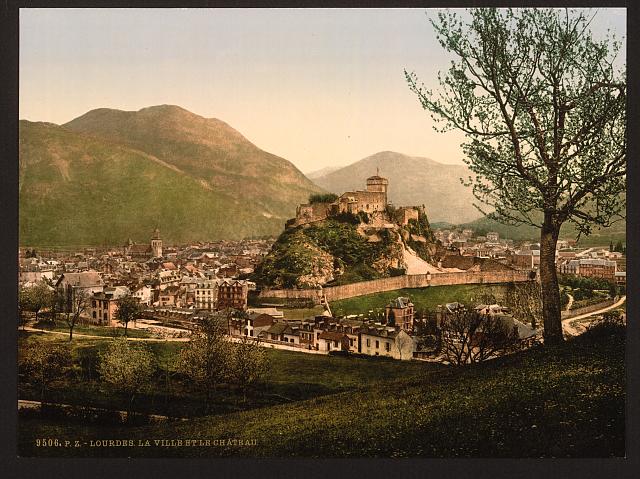

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons)

The Spanish Pyrenees, 2009 (Image courtesy of User Miguel303xm/Wikimedia Commons) The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)

The French Pyrenees, 2010 (Image courtesy of Nicolas guionnet/Wikimedia Commons)